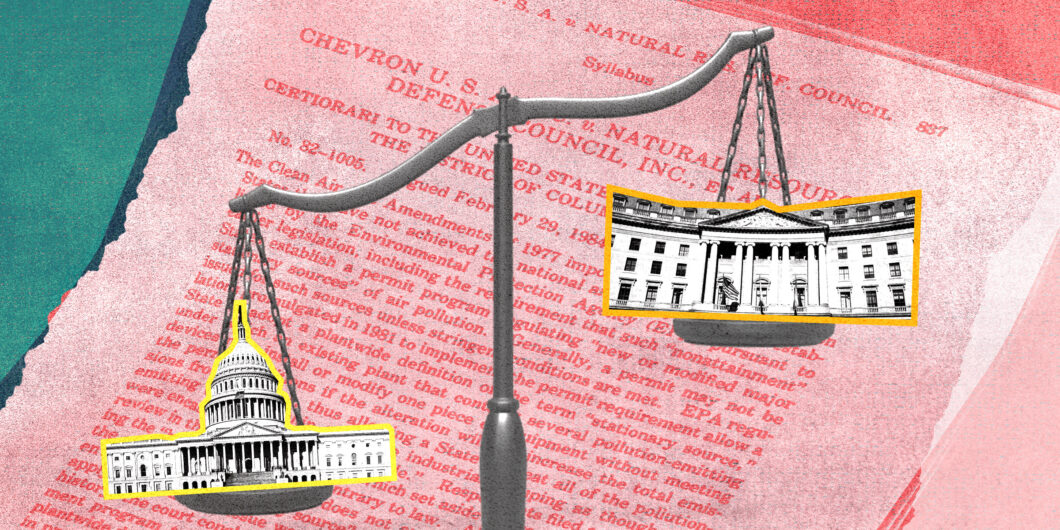

A World Without Chevron?

This Term, in Relentless, Inc. v. Department of Commerce and Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, the US Supreme Court seems poised to eliminate—or at least substantially narrow—its 1984 landmark administrative law precedent, Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council. In Chevron, the Court crystallized the doctrine that courts should generally defer to a federal agency’s reasonable interpretation of an ambiguous statute that Congress has charged the agency to administer.

In this Law & Liberty forum, Adam White pens a wide-ranging essay exploring what governance might look like if the Court were to overturn Chevron. He predicts that the modern regulatory state will not cease to function in a world without Chevron, and I agree on that front. But beyond that, I am left with many pressing questions in terms of separation of powers. I’ll focus on four here.

Will federal judges still strive to say what the law is, instead of what it should be?

The decade-long call to eliminate Chevron deference has largely come from libertarian and conservative lawyers and judges. As Professor White aptly captures in his opening essay, separation of powers has motivated these calls for reform. In the oversimplistic Schoolhouse Rocks version, Congress should legislate, agencies should execute those laws, and courts should interpret the laws as executed by federal agencies.

As Kent Barnett and I argue in the amicus brief we filed in defense of Chevron deference in Loper Bright, the separation-of-powers arguments against Chevron deference are not convincing as a constitutional matter. But as a policy matter, misapplication of Chevron deference may well discourage Congress from legislating with clarity and may encourage reviewing courts to be reflexively deferential, thus leaving federal agencies to play an outsized role in federal lawmaking.

In a world without Chevron, however, will other separation-of-powers problems emerge? In particular, it is a core separation-of-powers principle of the Federalist Society—a group of conservative and libertarian lawyers, of which I am a member—that “it is emphatically the province and duty of the judiciary to say what the law is, not what it should be.” Without Chevron, will judges be more tempted to say what the law should be, instead of just what it is?

Six years ago here on this Forum, I published an essay titled “The Federalist Society’s Chevron Deference Dilemma.” I pointed out that the Chevron decision itself was based on the judicially conservative ideal that judges must strive to decide cases not “on the basis of the judges’ personal policy preferences.” Policy judgments, when possible, should be left to the political branches, including federal agencies that are charged by Congress to implement the statutes and supervised by the President and presidentially appointed and Senate-confirmed agency leadership.

I do not expect Congress to do much in response [to Chevron’s demise]—just as it has shown little interest in responding to the new major questions doctrine.

In that essay, I reported the findings from an empirical study Kent Barnett, Christy Boyd, and I conducted on eleven years (2003–13) of the federal court of appeals decisions applying Chevron. In that study, we found that Chevron deference has a powerful constraining effect on partisanship in judicial decision-making. To be sure, we still found some statistically significant results as to partisan influence. But the overall picture provided compelling evidence that the Chevron Court’s objective to reduce partisan judicial decision-making had been quite effective.

In a world without Chevron, one would expect judges to find it harder to separate their judging from their politics. I hope courts will strive to have the judicial humility necessary to continue to defer to agencies when Congress has so directed. And having read thousands of circuit-court decisions dealing with Chevron, Congress regularly does so direct: Either the law runs out, or the best reading of the statute is that Congress has delegated broad policy discretion to the agency. Justice Kavanaugh’s concurrence in Kisor v. Wilkie comes immediately to mind (alterations mine):

To be sure, some cases involve [statutes] that employ broad and open-ended terms like “reasonable,” “appropriate,” “feasible,” or “practicable.” Those kinds of terms afford agencies broad policy discretion, and courts allow an agency to reasonably exercise its discretion to choose among the options allowed by the text of the [statute]. But that is more State Farm than [Chevron].

How will the Supreme Court manage increased disuniformity in federal law?

Nearly forty years ago in an article titled “One Hundred Fifty Cases Per Year,” Peter Strauss argued that Chevron deference promotes national uniformity in federal law by limiting courts’ responsibility for determining the best reading of a statute. Instead, courts need to assess only the reasonableness of an agency’s interpretation, rendering it more likely that lower federal courts across the country will agree in accepting or rejecting the agency’s interpretation. Moreover, by providing agencies space for interpreting statutory ambiguities, Chevron provides a disincentive for judicial challenges and thereby allows the agency to provide a national standard even absent judicial review. Justice Scalia, writing for the Court in City of Arlington v. FCC, embraced this rule-of-law value of Chevron: “Thirteen Courts of Appeals applying a totality-of-the-circumstances test would render the binding effect of agency rules unpredictable and destroy the whole stabilizing purpose of Chevron.”

To be sure, if Professor Strauss were writing that article today, he would have to re-title it Fewer than Seventy Cases Per Year. Over the last four decades, the Supreme Court has more than halved its merits docket. Without Chevron, we should expect much more disagreement and unpredictability in the lower courts when it comes to interpreting statutes that federal agencies administer. Will the Supreme Court be able to respond to bring more uniformity and predictability in federal law? Is there some other stabilizing force out there to help?

How will courts deal with prior judicial precedents based on Chevron?

Much time at oral argument in Relentless and Loper Bright was spent on trying to get a sense of how disruptive overruling Chevron would be for the thousands of prior judicial decisions that upheld an agency statutory interpretation under Chevron. At argument, Paul Clement, counsel for Loper Bright, gestured to the demise of legislative history and implied causes of action, observing that such demise “didn’t mean that every decision that was decided in the bad old days was overruled ipso facto.” He further argued that the Court could instruct lower courts to just ask whether the agency statutory interpretation was lawful. “And if the court has already held yes, it is lawful,” Clement continued, “I would think that would settle the matter.”

I am not as confident as Clement that we would see just a few judicial decisions overturned if Chevron were overturned. This is a main reason why I expect the Court to Kisor-ize Chevron, instead of overruling it outright. But if the Court were to overrule Chevron, it would be difficult for a federal circuit court to uphold a judicial precedent that says the agency’s interpretation is reasonable but not the “best” statutory interpretation—when the only reason for doing so is based on a doctrine the Supreme Court has just declared unlawful.

How will Congress respond, if at all?

Professor White spends much of his essay imagining how Congress may and should respond to a world without Chevron deference. I am less optimistic. I do not expect Congress to do much in response—just as it has shown little interest in responding to the new major questions doctrine. At most, perhaps Congress at the margins would legislate with a bit more clarity when it reauthorizes agencies’ organic statutes. The irony is that such clarity would likely come with unambiguously broader delegations, perhaps with the use of open-ended terms like “reasonable,” “appropriate,” “feasible,” or “practicable.” In other words, for those who feel like Congress has lost its legislative ambition, abandoning Chevron won’t be the cure.

I similarly do not expect Congress to amend the Administrative Procedure Act to codify Chevron deference, at least while the Senate retains the legislative filibuster. But I would love to see Congress, when reauthorizing agencies’ organic statutes, consider codifying Chevron deference as to certain agency statutory interpretations. As Kent Barnett has chronicled, Congress did that several times in the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010.

These are just four of the dozens of questions that come to mind when imagining a world without Chevron. It will be interesting to see how Congress, federal agencies, litigants, and lower federal courts react to Chevron’s demise (or at least further narrowing). On one thing I am certain: administrative law scholars will still have lots to study and write about when it comes to judicial review of administrative interpretations of law! To borrow a line from Justice Scalia’s dissent in National Cable & Telecommunications Ass’n v. Brand X Internet Services, “It is indeed a wonderful new world that the Court creates, one full of promise for administrative-law professors in need of tenure articles and, of course, for litigators.”