In a time where the average age of Supreme Court Justices keeps rising, lifetime appointments may not make sense anymore.

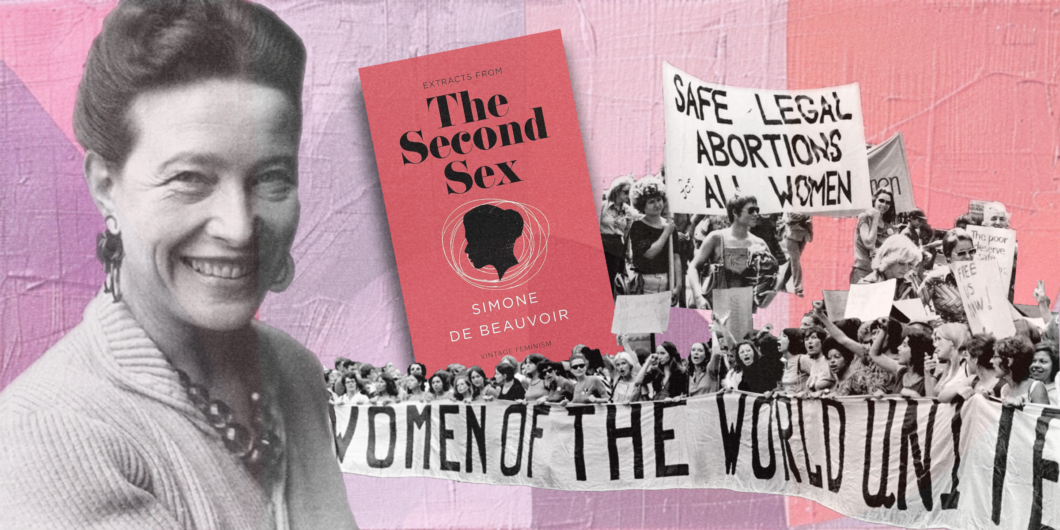

Feminism: Something to Talk About

I have little patience for Simone de Beauvoir and The Second Sex, which is full of erroneous arguments. Apart from her once being Catholic, there is little overlap in our personal biographies (though to her credit, she at least considered becoming a nun). Still, Emina Melonic opens her essay marking the 75th anniversary of The Second Sex with a Beauvoir quote even I can relate to: “I hesitated a long time before writing a book on woman. The subject is irritating, especially for women; and it is not new.”

Women, and perhaps today especially conservative women, don’t want to be the token woman who writes about women. Though we do believe there are differences between the sexes, and that women’s perspectives are unique in certain ways, it feels like we are accepting the premise of identity politics.

Sometimes we engage anyway, albeit reluctantly. I began writing about feminism because select conservatives (and so-called conservatives) were speaking about feminism, and women, in a ham-fisted and off-putting manner. And I suspect I am not alone in that reaction and concern.

The larger feminist point is that women have intellectual interests that have nothing to do with us being women. Mary Wollstonecraft, for example, argued against a coquettish education for girls. Women are rational beings, who, like men, have varying talents. For all the extreme degradations of Beauvoir and the Sexual Revolution, this is a truth we can now take for granted, in part because of feminism, though only in part. Jane Austen captured the same disputation through Mrs. Croft, who states, “I hate to hear you talk about all women as if they were fine ladies instead of rational creatures. None of us want to be in calm waters all our lives.”

Melonic raises some pertinent questions in her essay. The first is to ask, tongue in cheek, if feminism is still talked about. There are quite a number of reasons it is, and I’d like to focus on a few: We have not settled on a satisfactory definition of feminism with widespread recognition (and are unlikely to do so). Relationships between men, women, and the family and questions surrounding work are impacted by economic churnings and technologies, which are continuously shifting. And we are parsing out to what extent feminism is responsible for our current cultural ills.

Is Feminism Still Talked About?

Indeed, feminism seems to be growing in popularity. A group of academics and journalists contribute to Fairer Disputations, which publishes original work and compiles essays that promote “a vision of female and male as embodied expressions of human personhood,” and affirm “that men and women are equal in their dignity and their capacity for human excellence, yet distinct in many significant ways, particularly when it comes to sex, pregnancy, childbirth, and care for children.” Feminism is a frequent topic on conservative outlets like The Daily Wire, and in recent years, scholars like UnHerd columnist Mary Harrington, Notre Dame professor Abigail Favale, journalist Louise Perry, and Ethics and Public Policy scholar Erika Bachiochi have published thought-provoking books on feminism and the Sexual Revolution.

One reason for this could be that new technologies have created opportunities for conservative women, who sometimes take a break from their full-time jobs and careers to pursue the vocation of motherhood, to have more flexibility and maintain more engagement in the intellectual space. Their voices, as well as the perspective of women at other stages of life and in varying situations, could prove helpful (though not foolproof) in pulling feminism away from being ideological in the manner Melonic warns against: of one woman speaking for all and by turning “a legitimate grievance into collective victimhood.” They also could assist in moving feminism towards reflecting a “lived reality for women” (though working-class women still seem to be getting the short end of the stick). Overall, such a recalibration is likely good for conservatives, who haven’t always done so well with women.

What is Feminism?

Broadly, we are still talking about feminism because we lack a satisfactory definition. This is unlikely to be definitively settled, as feminism has always been a big tent with varying voices and coalitions, a feature that has its pros and cons. More to the point, the typical descriptions of the three waves of feminism, with second-wave feminism being equated with the Sexual Revolution, are often unnuanced and dissatisfying.

When many criticize feminism, they are really talking about the Sexual Revolution, which is more cohesive yet not entirely monolithic. The Sexual Revolution was a rolling movement that sought to undermine sexual norms and relationships and often warred against nature and the family. Modern “feminism” is an outgrowth of the Sexual Revolution (Judith Butler, for example, is much more akin to revolutionary Kate Millett than Mary Wollstonecraft or Susan B. Anthony). Many recognize that the Sexual Revolution was disastrous for the family and undermined the truth that human beings belong to each other, and more people seem to be rejecting the false promises of the Sexual Revolution.

The relationship between feminism and the Sexual Revolution is a messy one. Beauvoir herself demonstrates both the connections and tensions. She is widely considered a feminist (by what criteria is a good question), and her intellectual contribution of divorcing sex from gender is essential for the Sexual Revolution.

But her views are not in complete accord, and are overall more extreme, than Betty Friedan, whose book The Feminine Mystique, sold over a million copies in its first year despite her being unknown, an event that marks the start of second-wave feminism. Friedan believed in differences between the sexes and the value of motherhood (though she sometimes also disparaged it), while Beauvoir contended that:

No woman should be authorized to stay at home to raise her children. Society should be totally different. Women should not have that choice, precisely because if there is such a choice, too many women will make one.

Beauvoir was aiming to revolutionize society, while most women in the 1970s were in favor of improving the status of women. It seems fair to say that Friedan was more popular with everyday women, while Beauvoir rose in academia, evidencing that feminism speaks to multiple audiences.

Feminism and Technology

Parsing out the relationship between feminism and the Sexual Revolution is part of the renewed interest in feminism. So is understanding and addressing technological inventions and economic shifts that have changed how men, women, and families live, and even our comprehension of the human person.

In “The Sexual Revolution Killed Feminism,” Mary Harrington has suggested that the relationship between men, women, the family, and material conditions should inform a better definition of feminism, that feminism is:

A story of how men and women re-negotiated life in common, in response first to the transition into the industrial era, then into twentieth-century market society. If everyone today seems to be arguing about men and women again, it’s because we’re in the throes of another economic transition.

Along with Harrington, Erika Bachiochi has emphasized that the Industrial Revolution took men away from family farms, precipitating an unprecedented division between labor and home.

The rise of the knowledge economy and remote work present opportunities and challenges today. Remote work has the potential to reunite work and home. Women have done well, career-wise, in the global knowledge economy, while men without much education have been left behind in certain ways. If we are to renegotiate relationships between men, women, and the family, such phenomena are pertinent.

In short, we need less Simone de Beauvoir—and more Jane Austen.

In addition, innovations like the birth-control pill and synthetic hormones seemed to make the conquering of nature possible, contributing to the success of the Sexual Revolution. It’s hard to imagine people taking seriously the notion that gender is a social construct without such interventions. We are marching further down this path, with surgeries, reproductive technologies, and the looming possibilities of Artificial Intelligence.

Social media, the smartphone, pornography, and online dating have changed the way men and women live and relate to one another, making it more difficult for them to form relationships or even have face-to-face interactions. As Melonic notes, “We are experiencing great shifts in society, especially in terms of human relationship to technology, which has rendered us more alienated from each other.”

Is Feminism Responsible for Cultural Decline?

Certainly, many of the conversations surrounding feminism are about identifying to what extent feminism is responsible for our current societal ills. Thinking through this is useful in considering which feminist or Sexual Revolutionist ideas or policies would need to be rolled back for positive change. Rather than feminism being the single poisonous tree, the rise of expressive individualism (or, as I believe is more precise, expressive autonomy) seems to encapsulate our current malaise better, positioning the Sexual Revolution as both a cause and symptom of character and cultural shifts.

Expressive individualism is a combination of radical autonomy and the notion that the inner self is the true self, not necessarily reflective of or inextricably tied to the physical body. We live in a very self-focused subjective psychological world, with the rise of transgenderism, encouragements to achieve “self-actualization,” prioritize “me time” and “self-care,” and exhortations like “pursue your truth.” Relationships and morals are viewed as restrictive and burdensome, rather than ennobling and necessary for human flourishing.

Public policy professor Andrew Cherlin demonstrates in The Marriage Go-Round that America’s churches, by shifting from a spirituality of dwelling to a spirituality of seeking, played a role in promoting expressive individualism. “The spirituality of seeking was not about laws or doctrines but about finding a style of spirituality that made you feel good, that seemed to fit your personality.” By around the 1950s, expressive individualism had captured the American mind. It had a tremendous impact on the stability of marriages, subverting the Christian view of marriage with an individualized romantic view based in emotional satisfaction. Religious denominations loosened laws pertaining to divorce simultaneously with, and even prior to, no-fault divorce, which led to further marital breakdown.

In The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self: Cultural Amnesia, Expressive Individualism, and the Road to the Sexual Revolution, theologian Carl Trueman traces the intellectual roots of expressive individualism, outing philosophers like Karl Marx, Jean Jacques Rousseau, and Beauvoir and psychologist Sigmund Freud. Likewise, Hillsdale College professor Kevin Slack identifies psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich as the “father of the modern sexual revolution in the US” and notes that Reich also influenced New Leftist Paul Goodman.

This exercise raises some provocative questions: To what extent is the Sexual Revolution a project of feminism versus the arguments and political machinations of the New Left? Are certain religious denominations more susceptible to the degradation of expressive individualism and have they, in their warped form, even contributed to promoting its spread? Do we believe the lack of family formation and family separation today is mostly a rejection of marriage as a patriarchal capitalistic institution or because the purely romantic view of marriage, which brings with it almost unattainable standards for spouses and marriage, dominates?

Perhaps there is simply more than one way to tell the story of familial and cultural breakdown. Yet first-wave feminist’s advocacy for women’s political equality seems unrelated to the development of expressive individualism.

Further, these analyses demonstrate the magnitude and complexity of the problem we are facing. As Melonic notes, feminism feels like a peripheral issue when “we must first defend our humanity—our whole Selves—not just some aspects of who we are.” We don’t even agree on what it means to be human, that there is an objective and observable truth, or the primacy of reason.

Finally, thinking through these questions helps us see the Sexual Revolution as both a contributor to and a manifestation of the shift from the human person to the psychological self. Beauvoir is crucial to the rise of expressive individualism, since she promoted a false anthropology that divorced sex from gender.

But to turn back to Betty Friedan, we can see in 1963’s The Feminine Mystique, that the psychological self was already part of the social imagery. Friedan relied on the work of Abraham Maslow, who promoted the needs theory and the pursuit of “self-actualization.” In his view, according to Alma Acevedo, “ethical norms are neither consistent, universal, nor communicable, but precariously shut into the individual’s ‘private psychological world.’ Moral good is not what everyone ought to will, but what self-actualizers desire.” Friedan’s basing of her arguments on such false ideologies demonstrates that they indeed had an appeal, and in turn, her work contributed to their spread.

What Now?

Having discussions about feminism, defining it, and considering its relationship to the Sexual Revolution is academically compelling and useful in some ways. However, to find our way out on the ideas front, we will likely have to turn to sources that put forth a robust understanding of the human person, like the theology of the body, and natural law. The disagreements are fundamental and deep, beyond feminism.

Practically, and probably more essentially, we need to move towards embodied interactions and promote role models. Men and women tend to learn how to be virtuous by imitating other good men and women; the breakdown of marriage and dad deprivation (and the ascendance of the online world) are significant sources of the confusion over what it means to be an admirable man, woman, and spouse.

While examples in the real world are best, cultural portrayals of men, women, and marriage have significant effect. As Melonic argues, “literature, art, and film have revealed the complexities of being a woman better than any feminist or philosophical tract can even dream of doing.”

In short, we need less Simone de Beauvoir—and more Jane Austen.