Nostalgia for the Smoke-Filled Room

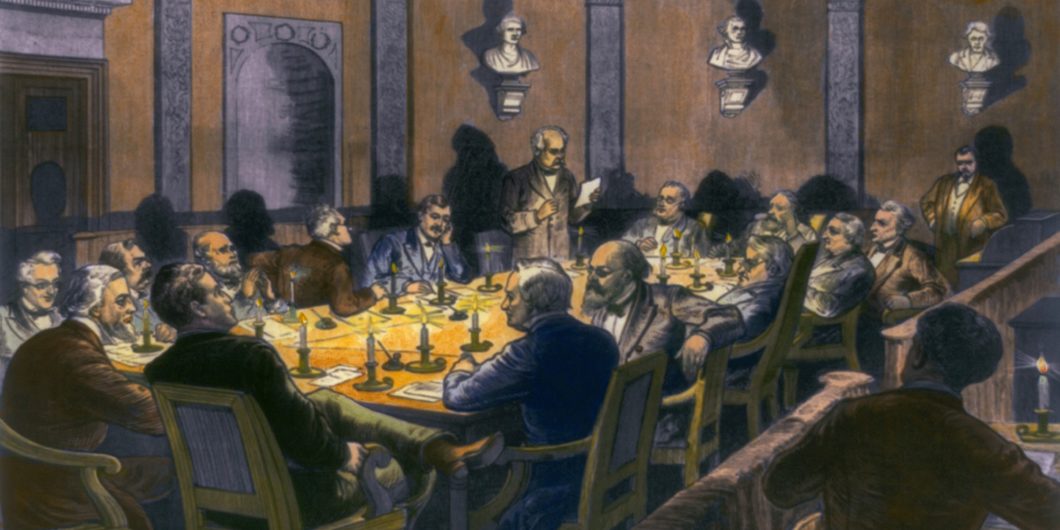

Eitan Hersh, an associate professor of political science at Tufts University, mourns the passing of the smoke-filled room. Well into the 20th century—and right up through 1968 in the late Democratic Mayor Richard J. Daley’s machine-politics Chicago—there was no such thing as simply deciding to run for public office and then amassing the money and organization to put together a campaign, à la Donald Trump, Bernie Sanders, or Pete Buttigieg. Candidates were handpicked by party mucky-mucks who drew on elaborate hierarchies of local patronage to turn out the vote for the individuals they endorsed. This meant that political power devolved down to fine-grained neighborhood levels: in Daley’s Chicago the precinct captains answered to the Cook County Democratic Committee. The captains, like their counterparts elsewhere in America, racked up votes by providing local voters with concrete services like municipal jobs, rodent extermination, legal assistance, and even cash to help out with rent and bills.

The working-class voters presumably cared little about the larger state or national policy issues on which a particular nominee might take a position. They were happy enough with the brand-new garbage cans and low property-tax bills that the ward heelers and neighborhood Democratic clubs delivered. Hersh’s book is a contrarian focus on the positive side of Tammany Hall-style politics and a touted blueprint for adapting it to the 21st century.

The Decline of the Machine and Rise of “Political Hobbyism”

The smoke began to clear from the back rooms as early as the 1880s, with the rise of the Progressive movement, backed by a growing and increasingly educated middle class, which regarded this species of transactional politics as vote-buying and worse. “Patronage, bossism, and raucous political parties were an affront to middle-class tastes,” Hersh writes. The Progressive reformers sought to break down the political parties as intermediaries between voters and the government and “let voters participate in politics without that corrupt influence.” One goal of the Progressives—fairly successfully achieved—was the substitution of primary elections for back-room candidate selection.

Still, as late as 1968, local party insiders controlled the power to pick the delegates to the national conventions at which presidential candidates were nominated. Some latter-day Progressives, namely youthful, impressively degreed anti-Vietnam War liberals, tried to introduce their own delegate slates at the 1968 Democratic convention (in Daley’s Chicago) that would vote for the ultra-anti-Vietnam War candidate Eugene McCarthy instead of the insider pick Hubert Humphrey. But they were rebuffed by clever party bosses who switched around meeting times and locations and even, on one occasion recounted by Hersh, delivered a knock-down punch in the jaw to one of the McCarthy liberals. That, plus Daley’s aggressive and extensively televised use of Chicago police to quell rioting at the convention by antiwar protesters, led to hastily mounted Democratic Party reforms (with Republicans following suit). These included transparency rules and an ironclad requirement that state delegates to presidential conventions be chosen either by government-run primaries or by caucuses open to all voters—that is, the system that prevails today.

Now, a cynic might point out that party insiders have actually managed to do pretty well for themselves despite the reforms. In both the 2016 and, currently, the 2020 presidential races, Democratic Party higher-ups have ruthlessly derailed the campaigns of the popular but unelectably leftist Bernie Sander in order to ensure the nomination of candidates they deemed more viable: Hillary Clinton in 2016 via the use of “superdelegates,” and Joe Biden in 2020 via what looked like orchestrated endorsements by swiftly dropping-out rivals. Furthermore, such newly resurrected (and staunchly Democratic-backed) practices as ballot-harvesting, voting by mail, and adamant opposition to any form of voter-identification at polling places threaten to bring back, in different forms, the proxy-voting and stuffed ballot boxes that were septic features of the old system. But that is not the book that Hersh has written.

While admitting that machine politics in the old days often fostered racism, exclusion of outsiders, and self-enrichment, Hersh argues that doing away with machine politics had a terrible cost: the death of meaningful individual and local participation in political life. When local party bosses and precinct captains lost their power—when Progressive civil-service reform eliminated patronage jobs to be handed out and Progressive election reform eliminated the ability to trade social services for votes—few people with better things to do wanted to be local party bosses or precinct captains. That is because, Hersh contends, “[W]hen ordinary Americans volunteer in politics, they are trying to acquire power. Each voter they convince is a small piece of that power.”

How many people have ever actually yearned to wield political power, either in the backroom or at the front door?

Not only did local party hierarchies which, for all their faults, served genuine human needs, melt away when deprived of power, but the high-minded, highly articulate, and often well-financed elites who now dominated the American political scene (half the delegates to the 1976 Democratic convention were lawyers and other professionals) were and remain typically more interested in large-scale, semi-abstract issues such as environmental regulation and various concepts of racial justice than in the bread-and-butter concerns of either their own neighborhoods or anyone else’s.

The result, as Hersh describes it, has been the rise of what he calls “political hobbyism” on the part of the college-educated: avid consumption of political news that is typically accompanied by avid emotional engagement in the form of venting—either in-person to one’s family and friends, or on various social media platforms and the occasional signing of online petitions. They might consider themselves “informed citizens…spending significant time and energy on politics,” but in fact, they are engaging in a “leisure activity…similar to the activities of sports fans or at-home foodies.” Hersh writes: “[W]hen people engage in political hobbyism, power is the reason that politics is exciting to them. In contrast, when people do politics, power is not just a topic, it’s the goal.”

Must We All “Do Something”?

Hersh’s aim in this book is to get these credentialed duffers off their laptops and into the trenches of actually accomplishing something political—that is, turning their political sentiments into political clout on a local scale. This is where the book seriously falters. First of all, Hersh, a self-proclaimed Democrat, isn’t very interested in Republican grassroots political activism, except for a few passing references to the successes of the Tea Party and gun-rights movements in rousting political amateurs to action during the Obama years. His book is primarily an inspirational tract for his fellow Democrats (since, as Hersh himself points out, the political-hobbyist class is, besides being disproportionately college-educated, disproportionately Democratic in affiliation), especially Democrats dismayed—as Hersh himself seems to be—that Trump is living in the White House.

So Hersh casts about for inspirational people whose political trajectories and successes his readers might emulate. One of them is Lisa Mann, an architect in her “midfifties” living in Brooklyn’s affluent Park Slope neighborhood who gets fired up enough by Trump’s election to trek to Staten Island every weekend going from door to door with a group of likeminded souls who try to talk the residents of New York City’s lone Republican borough into voting Democratic in the 2018 congressional election. And in fact, a Democrat, Max Rose, flips the seat, perhaps—although perhaps not—owing to the “deep canvassing” efforts of Mann and her ilk. (Establishing causality is not one of the book’s strong points.)

Then there’s Drew Kromer, a sophomore in 2018 at Davidson College, an island of Democrats in otherwise solidly Republican Mecklenburg County in North Carolina. Kromer engineers a student takeover of the disorganized Democratic Party chapter in the college’s precinct and throws the precinct’s weight behind Democratic state legislature candidate Christy Clark, who wins the election by 415 votes. Kromer gets invited to Democratic Governor Roy Cooper’s Christmas party.

Finally, there is Angela Aldous. A veteran of the 2011 occupation of the Wisconsin State Capitol by public employees protesting then-Republican Governor Scott Walker’s campaign against public-employee unions (she worked as a nurse for the University of Wisconsin’s hospital system), Aldous has moved to blue-collar Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, with her husband and lain politically dormant until—Trump. On the day of his inauguration, she downs an entire container of Oreos and starts a journal in which she vows to “do something” every single day to resist his presidency. And so she does: watching resistance videos, attending organizing training sessions, and ultimately creating a group of about 50 kitchen-table regulars (plus a mailing list of hundreds), the Voice of Westmoreland (VOW), that probably includes every last liberal to be found in this pocket of western Pennsylvania MAGA country.

As with Mann, door-to-door canvassing is Aldous’ specialty. VOW takes credit for getting a Democrat, Conor Lamb, elected to Congress by 755 votes in a February 2018 special election—although Lamb’s victory might have also been owing to the fact that his Republican and staunchly anti-abortion predecessor, Tim Murphy, had been forced to resign after it was revealed that he not only had engaged in an adulterous affair but had urged his mistress to have an abortion. Hersh seems enthralled by Aldous. “I realize I am talking to an American hero,” he writes after summarizing a phone interview. In turn, VOW’s website features a pitch for Hersh’s book.

Conspicuously absent from the resumés of this trio, however, is the quid—the community service—that Hersh argues must be given in exchange for the quo of genuine local political power. Only Aldous does a bit of it, occasionally driving “undocumented” VOW members to doctors’ appointments and spurring VOW to chip in for gas cards and diapers for members laid off when the federal government briefly shut down in 2019. The rest of the actions of all three—mailings, going door to door, and so forth—are conventional volunteer political activity, or, as may be the case with Kromer, preparation for a full-time career in Democratic politics (he is currently enrolled in law school). Indeed, it is arguable that what the three are actually engaging in—especially Aldous with her Trump resistance journal—is simply a glorified, more interactive form of exactly the political hobbyism that Hersh decries elsewhere in his book. Their goal looks more like self-fulfillment than actual political power.

Perhaps aware of this problem, Hersh fleshes out his account with a fourth, more convincing profile: Naakh Vysoky, the unofficial boss of the Russian-Jewish immigrant community in Boston’s Brighton neighborhood. For decades Vysoky and his wife drove elderly immigrants to their physicians, gave them English lessons, and helped them study for citizenship tests, in turn producing votes for legislative candidates who could get the immigrants’ snow shoveled, for example. But Vysoky, who died on December 31, 2019, after Hersh’s book went to press, was already 98 when Hersh interviewed him: a throwback to an earlier era.

One problem is that it is not so easy as it once was to be a favor-trading ward heeler. Hersh relates his own recent foray into community organizing: setting up a Democratic Party-sponsored phone bank in his suburban Boston neighborhood. He wanted to expand to provide babysitting services, gift cards for gas and groceries to those in need, and similar goods and services—but discovered that state campaign regulators, restrained by Progressive reforms, take a dim view nowadays of such giveaways by political entities.

The other problem is simpler: How many people at any given time have ever actually yearned to wield political power, either in the backroom or at the front door? It seems like a niche ambition that is not for the faint of heart. “Power is getting ten, fifty, a hundred, a thousand people to vote the way you want,” Hersh writes. Just reading that sentence, much less contemplating ringing dozens of doorbells on a dreary Saturday, made me want to do anything else: bake a cake, start a Dickens novel, or, well, surf the internet for juice on Joe Biden. Sorry, but I, apparently like most Americans these days, actually like being a political hobbyist.