Movement conservatism never fully understood the deeper sources of human conduct and the depth of the problems America faced.

Every Word in Its Proper Place

Every book by Joan Didion is a short book. Her two most famous, Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968), and The White Album (1979), are 238 and 222 pages respectively, and the most widely read of her five novels, Play It As It Lays (1970), is just a little longer, at 240 pages. Her recent memoirs, The Year of Magical Thinking (2005), and Blue Nights (2011), chronicling the deaths of her husband, the novelist John Gregory Dunne (heart attack), and her adopted daughter, Quintana (acute pancreatitis), clock in at 240 and 208 pages. This latest book, a collection of reprinted magazine essays and book forwards titled Let Me Tell You What I Mean, is a mere 149 pages, although a 35-page introduction by Hilton Als, a drama critic for the New Yorker, pads the total up to a more respectable 184, so it is not quite Didion’s shortest book, which seems to be Salvador (1983), a 110-page repackaging of two articles she wrote for the New York Review of Books about a trip she and Dunne had made to that Central American country nearly forty years ago when the hordes of journalists who descended there to cover its left-right civil war liked to leave out the “El” in its name, in contrast to today, when El Salvador’s chief interest to journalists is that Donald Trump reportedly called it a “s—hole” in 2018.

Let Me Tell You What I Mean, besides being one of Didion’s shortest books, is also one of her smallest physically, at 5 by 8 inches, so a reader is entitled to wonder whether she is getting her money’s worth at the $23 list price. For nearly the same price, $23.99, for example, one can purchase the Library of America’s Joan Didion: The 1960s & 70s (2019), a fat, 980-page compilation of five entire books of hers, including Slouching, Play It, and The White Album.

Six of the twelve essays in Let Me Tell You What I Mean are reprints of columns that Didion, alternating with Dunne, wrote for The Saturday Evening Post for several years until the magazine’s demise in 1969. All six date from the same year, 1968, and because the Didion/Dunne columns had a word limit of about 1,200 words, they are very short essays indeed, and it is one of the marvels of a book with 5 by 8-inch pages that a 1,200-word essay can stretch out to fill seven of those pages. One of the Saturday Evening Post offerings, “Pretty Nancy,” in which Didion watches Nancy Reagan, the wife of the governor of California and not yet the wife of the president of the United States, fake the picking of rhododendron blossoms from her Sacramento garden for a television shoot, also appeared as a reprint in shortened form in The White Album, so here it is, in a sense, a reprint of a reprint. Another double reprint in Let Me Tell You What I Mean is “Why I Write,” which appeared first as an article in the New York Times Magazine in 1976, then as an entry in an anthology titled The Writer on Her Work in 1980 before it landed here. A third essay, “On Being Unchosen by the College of One’s Choice,” dating from that year of magical Saturday Evening Post reprint thinking, 1968, about the rejection letter she had received from Stanford as a high-school senior that obliged her to attend the University of California-Berkeley instead, has been posted on the now-defunct website College Admission since at least 2013.

It is easy to parody Didion’s style, with its deliberate repetitions that result in sentences that are perhaps a good deal more meandering and elongated than is ordinarily called for.

This is not to say that the rather old and occasionally shopworn material in this rather slender volume (the latest-written essay, for the New Yorker and about Martha Stewart and the Martha Stewart industry, dates from the year 2000) is not worth reading. Every one of the twelve essays is marked by the precise, diamond-drill rigor that Didion, by her own account, labored over with countless rewrites to put every word into its proper place in her very long and rhythmic sentences, and by her preternatural powers of observation that enable her to pinpoint a detail of dress or demeanor or language inflection or interior decoration, tiny to nearly the point of imperceptibility, that tell a reader everything he needs to know about the person she is describing, as in this about Nancy Reagan’s voice:

‘Indeed it is,’ Nancy Reagan said with spirit. Nancy Reagan says almost everything with spirit, perhaps because she was an actress for a couple of years and has the beginning actress’s habit of investing even the most casual lines with a good deal more dramatic emphasis than is ordinarily called for on a Tuesday morning on Forty-fifth Street in Sacramento.

It is easy to parody this style, with its deliberate repetitions that result in sentences that are perhaps a good deal more meandering and elongated than is ordinarily called for—just as it is easy to parody the style of Ernest Hemingway, whose sentences Didion writes, in “Last Words,” her essay about Hemingway (the New Yorker, 1998), she studied over and over, down to the punctuation marks, as a teen-ager practicing to be a writer herself. As with Hemingway, however, when Joan Didion is good, she is very, very good, and her darts, tiny, slender, and sharp as silk pins (those appear in a 1966 Saturday Evening Post essay that is sadly not in this book but can be found online), hit their targets on the bulls-eye.

The problem with Let Me Tell You What I Mean isn’t the quality of the material, but why much of it is reappearing at all in 2021. The Saturday Evening Post column “Alicia and the Underground Press,” observes how much more truth, not to mention sheer liveliness, was to be found in the subjective takes on events in the countercultural “alternative” urban newsweeklies that mushroomed during the 1960s than in the staid accounts of the mainstream press. Except that this is not 1968, or even 1998, and there are no more alternative newsweeklies for all intents and purposes, the underground press having been killed or reduced to inconsequentiality by the internet. The Martha Stewart essay, “Everywoman.com,” is as brilliantly observational as anything Didion has written, pointing out that Stewart, contrary to what leftist journalists have written about her ad nauseam, wasn’t, in building her massive multimedia empire, capitalizing on ordinary women’s anxieties about being able to maintain the picture-perfect, handcrafty households photographed in Martha Stewart Living. Rather, Stewart cashed in on their fantasies—shared, Didion admits, by herself—that they, too, if they put their minds to it, could build a billion-dollar company out of such everyday homemaking skills as canning, baking, decorating, and catering. But the Martha Stewart story didn’t end in 2000, when the New Yorker published Didion’s essay. It went on and on, to include Stewart’s 2004 conviction and imprisonment for lying to the FBI about a stock trade, her self-proclaimed redemption and clawback of her company from the men who took it over, the company’s ultimate acquisition, nonetheless, by an even larger entity, and Stewart’s current sort-of retirement at age 79, her star having faded somewhat. Stewart has outlived what even Didion had to say about her.

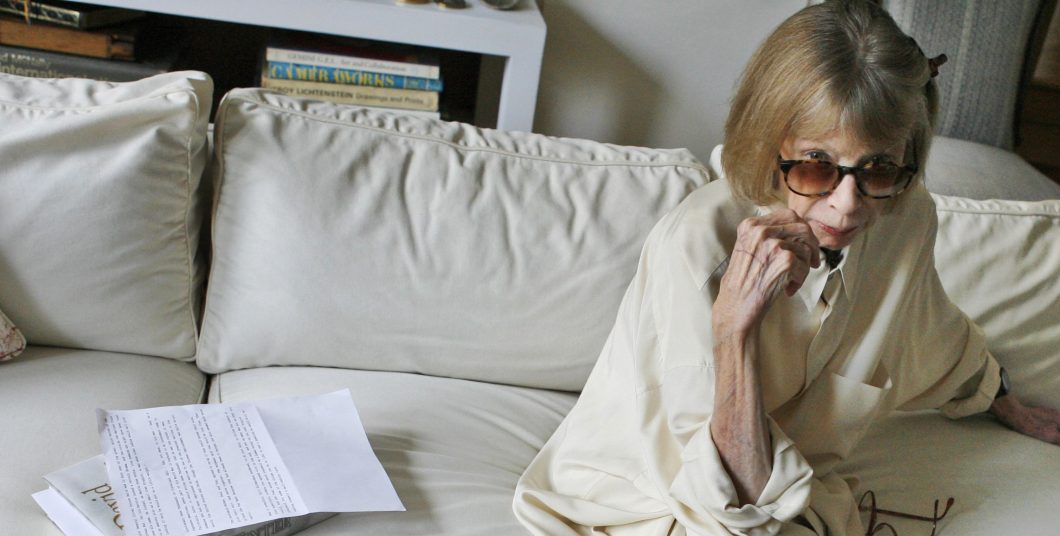

And that leads to the other problem: Joan Didion, who is now 86, retired from writing after Blue Nights, that is, ten years ago. As the Atlantic writer Caitlin Flanagan pointed out in a review of that book that is probably the most perceptive critique of Didion’s writerly strengths and weaknesses to date, Didion was at heart, and is remembered best as, a young woman, with a young woman’s fresh, often introspective take on the scene around her: the hippies of Haight-Ashbury, the freeways of Los Angeles, the compassless inner lives of the prosperous in the sun-burnished, not yet-overpopulated California of the 1960s and 1970s. Her best work, the work that made her an iconic figure, was her work—her magazine pieces—during that period: Slouching Towards Bethlehem and The White Album. Let Me Tell You What I Mean pays homage to that sparkling time, and to readers’ nostalgia for it, with a dustcover photo of a 30-ish Didion wearing a modish shift-dress, lit cigarette in hand, looking pensive but mostly straight at the camera to command its attention. Her later work, with a few exceptions, deteriorated: the pieties about “Salvador” and elsewhere that the progressive New York Review of Books readership wanted to see in print, and, most recently, the memoirs in which introspection seemed to have crumbled into tiresome self-absorption and style into annoying tics. But the market for books by Joan Didion remains as hungry as ever, and thus the current flow of reprints from the past, of which the 2019 Library of America volume is Exhibit A. And by now, in Let Me Tell You What I Mean, we can hear the distinct sound of the scraping of the bottom of the Didion barrel. Hilton Als, in his rambling forward that is longer than any of the book’s contributions by Didion, strains to find something fresh to say about his subject (“Didion, a carver of words in the granite of the specific”), but mostly fills his allotted pages by summarizing and quoting large chunks from the contents and other, better-known Didion works.

Still, it doesn’t hurt, I suppose, to read “Why I Write” one more time, or finally to see the unabridged version of “Pretty Nancy.” And there is one essay in the book that has not lost its capacity to move the reader, even to tears, even after all these years. It is “Fathers, Sons, Screaming Eagles,” a Saturday Evening Post column from 1968. Didion attends a reunion in Las Vegas of the 101st Airborne Division, which jumped into Normandy and was besieged at Bastogne. These are the survivors, and they now have sons serving or getting ready to serve in Vietnam. One man’s son is already missing in action, and another is not eager to see his teenager risk death. “[P]erhaps it was not such a great adventure this time,” Didion writes. “Perhaps it was hard to bring quite the same urgency to holding a position in a Vietnamese village or two that they had brought to liberating Europe.” Vietnam was not the last time the Screaming Eagles spent their valor in Washington-instigated wars far away whose urgency has been difficult to discern. Iraq and Afghanistan come to mind. Of all the essays in Let Me Tell You What I Mean, this one is not stale.