Why Conservatism Failed

Serious observers of the American political and intellectual scene can hardly doubt that American conservatism is in disarray. A number of incompatible notions of conservatism contend with each other. Why all this fragmentation and controversy? There is no simple answer, but a new book by the present author relates the disorientation to the conservative movement having failed to achieve its long-standing objectives and to its being hampered by old, by now perhaps chronic, weaknesses.

It was in the decade after the Second World War that a self-consciously conservative intellectual and political movement began to take shape in America. It had major thinkers in fields like history, political theory, law, sociology, literature, and economics. The publication of Russell Kirk’s 1953 book The Conservative Mind was a watershed event and earned him the reputation as “the father” of modern American conservatism. William F. Buckley Jr. and his magazine National Review (founded in 1955) played a central role in connecting ideas with practical politics. The magazine provided the intellectual rationale for a political alliance of disparate groups, including libertarians, traditional Catholics, and other traditionalists. Intellectual consistency took a back seat to forge a rough political consensus.

Considering its own standards of success, how well has conservatism done in the last 75 years?

The movement wanted to shore up traditional Western civilization with its ancient Greek, Roman, and Christian resonances and opposed what it called the Leviathan state. Totalitarianism had been defeated in Germany, but it still existed in the Soviet Union, and in America, Big Government was being advanced by progressive intellectuals and politicians.

The movement reaffirmed the American system of limited, decentralized constitutional government. The moral-spiritual values that it saw as informing the Constitution were fading in the universities and other American institutions. This cultural change ultimately threatened the rule of law and traditional liberties. In economics, the movement advocated free markets and fiscal discipline in government.

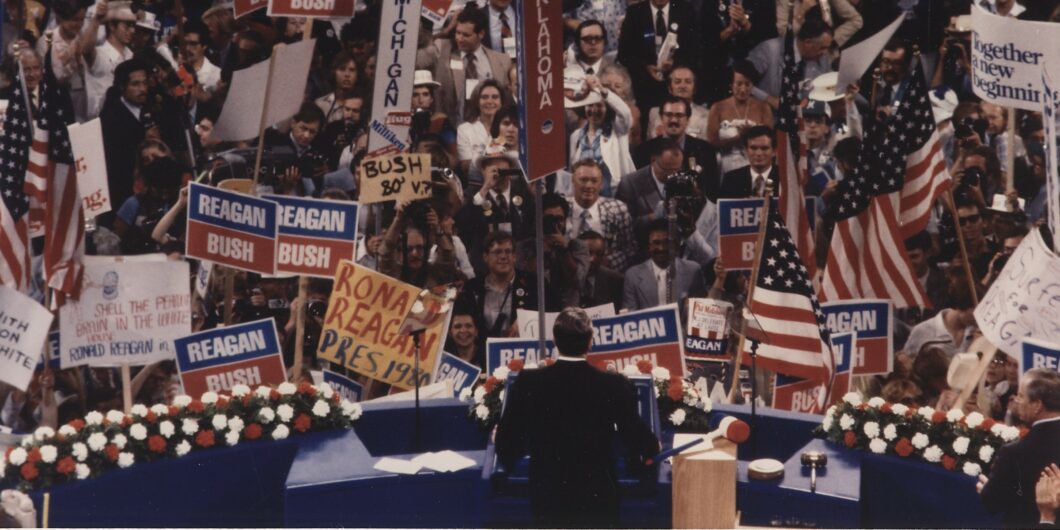

Conservatism seemed at times to be making considerable progress. During the Ronald Reagan presidency, representatives of the movement even declared that conservatism had finally “triumphed.” This notion illustrated a rather superficial view of the state of America and of what sets the long-term direction of a society. In the 1980s, developments within the general culture, specifically, the universities, did not point in the direction of triumph. As can be seen even more easily today, conservatism had not been able to reverse the deeper social trends that it opposed and that were shaping the future.

The American federal government has expanded dramatically and become progressively centralized. Federalism has greatly weakened. The US Constitution has been, in important respects, abandoned. For example, the power to go to war, which the Framers very deliberately and explicitly assigned to Congress, has been absorbed by the Executive. An elaborate national security state with an almost unlimited capacity to surveil Americans has been constructed, and government and social media, in tandem, routinely censure disapproved opinions.

President Eisenhower warned against “the military-industrial complex,” but its size and power has only grown. The influence of Big Finance and Big Business is greater than ever. The US is today far less a constitutional republic than a plutocracy in which regulations and markets are heavily biased in favor of large economic interests.

“Fiscal discipline” is just about the last phrase that might be used to describe the financial management of the federal government. Enormous deficit spending has become routine, and the size of the national debt far exceeds that of the GNP—conditions that economists and politicians in the 1950s would have considered nightmarish.

Crime, including murder, is more rampant and egregious than ever, and in many places, the rule of law is only selectively enforced. Drug abuse is everywhere.

As for the traditional values admired by the old conservatives, they have been replaced in America’s most influential institutions, including the universities, and in private life, even in some churches, by their virtual opposites, woke and cancel culture.

Conservatives have over the years spent incredible amounts of money on winning elections and influencing policy views in the US Congress and elsewhere. Yet it has had little effect on general social trends. Liberal progressives and leftists would like to think that conservatism was backward from the start and was bound to be defeated by superior ideas. The chief reason for conservatism’s failure is quite different: The movement misdiagnosed the problems it faced and adopted the wrong priorities.

In the early days, leading conservative intellectuals, Kirk prominent among them, pointed to the general culture as shaping the evolution of society. It was the life of the mind and the imagination—in religion, the universities, literature, movies, music, the other arts, and the media—that gave people their basic view of reality and formed their sensibilities. According to Kirk, ”the culture” created their deepest hopes and fears and predisposed them to certain political attitudes. A like-minded thinker, who had come to public attention even earlier, was Peter Viereck. The two had been deeply influenced by the great Harvard professor Irving Babbitt (1865–1933), who had contended that the imagination plays a central role in forming the lives of individuals. A healthy society presupposes citizens with a blend of sound moral character and sound imagination. Kirk, Viereck, and others argued that unless America’s deteriorating moral-spiritual, intellectual, and aesthetical culture was redirected by a creative cultural traditionalism, a warped sense of reality would destroy what remained of Western civilization and America’s constitutional order.

Plenty of intellectuals have written about “principles” . . . but rarely have their discussions of the ultimate questions moved above the level of broad generalities, and they have typically advanced preconceived ideological and political conclusions.

But a different view of what was most needed would become dominant in the conservative movement: The way to make change was to win political power. The editorial line of Buckley’s National Review was paradigmatic. It was an intellectual magazine, but, without the editors fully realizing it themselves, ideas became for them largely a means for winning political victories, especially presidential elections. This sense of priorities drew attention and resources away from the need to change the culture.

The movement was affected by a deeply rooted but dubious form of American pragmatism, which tends to discount the importance of mind and imagination and sometimes borders on the philistine. Consider the amount of attention paid in the news media to presidential politics, elections, and battles in the US Congress. Could any sphere of activity possibly influence the lives of Americans more? Does not the power to shape the future ultimately reside in Washington, DC?

In the 1980s when the movement celebrated the “triumph” of conservatism, people more attentive to “the culture” could see that developments there were actually continuing to radicalize the American mind and imagination. The New Left and Counter Culture of the 1960s and ’70s had not been transitory aberrations. They reflected broad, long-discernible trends within Western society that were undermining or replacing classical and Christian beliefs. Woke and cancel culture are but extreme new manifestations of the same general trends. It is those trends that have produced the progressive radicalization of American politics and that keep surprising and confusing conservatives.

The movement never fully understood the deeper sources of human conduct and the depth of the problems it faced. Politics can in some circumstances be supremely important, but there can be no realistic and effective political action without proper diagnosis of the problems to be addressed and without understanding the limits of politics.

The movement has not ignored ideas. Plenty of intellectuals have written about “principles” and advocated things like “great books” programs, but rarely have their discussions of the ultimate questions moved above the level of broad generalities, and they have typically advanced preconceived ideological and political conclusions, as when the arch-elitist Plato has been shown to be actually a defender of “democracy.” Some movement conservatives have spoken of the crucial role of the arts and the imagination, but rarely have they tried to explain in depth just what the imagination is or just why it so strongly influences human beings.

The movement never achieved a mature philosophical culture. Perhaps the best example of this weakness is that many supposedly conservative thinkers endorsed an anti-historical view of higher values and human existence generally. They were attracted to the view of Leo Strauss and his disciples that when it came to understanding higher values there was nothing to be learnt from history and tradition. Only abstract, ahistorical principles matter. Yet the father of modern conservatism, the British thinker-statesman Edmund Burke, had famously emphasized the opposite. He dreaded the abstract ideas of the French Revolution. He argued that, in isolation, individuals and individual generations have meager moral and intellectual resources. But through an intergenerational effort, we can gain access to and creatively bring forward the wisdom of mankind, what Burke called “the bank and capital of nations and of ages.” Here he made explicit and developed a predisposition that had long been implicit in Western civilization, especially in Christianity. His inclination ran parallel to that of the US Framers. For example, in the Federalist Papers, James Madison explicitly endorses relying on experience and rejects thinking like an “ingenious theorist” who is planning a constitution “in his closet.” How paradoxical that in endorsing ahistorical, abstract natural right thinking and rejecting the guidance of history, many members of a supposedly conservative American movement were attracted to an intellectual posture heretofore associated with leftists and revolutionaries.

Preoccupied with winning elections and policy debates and disinclined to pursue the more demanding questions of mind and imagination, the movement was eventually overwhelmed by the cultural trends that it had largely ignored. Even its notion of politics was truncated. Now that conservatism is in a state of disorientation, one wonders whether its deep-seated intellectual and other habits will stand in the way of urgently needed self-examination and soul-searching.