The Gap Between Law and Morality

“That dog is worth more than their child,” my mother said.

The dog was a guide dog, killed when a driver mounted the curb in a nearby town. The child belonged to another local family and had some form of mental retardation. Both the blind woman’s dog and the retarded boy were known to us. The first because my mother volunteered for various charities, and the second because I went to primary school at the historical moment when there was an attempt to integrate at least some disabled children into mainstream schools. Mum did not approve of this. “An army marches at the pace of its slowest soldier,” she said.

There’s a psychiatric phenomenon called “moral dumbfounding.” It manifests when you think something is evil or disgusting, and you want to say it’s immoral, but you can’t think of a reason why it’s immoral. So, you end up saying it just is. I was, I think, seven at the time my mother ranked a dog above a human being, but I recognise in the recollection of her comment my first experience of moral dumbfounding. How could a dog be worth more than a child, even a stupid one who sat, dough-like, at his desk day-after-day, unable to write his name?

We were farmers, which meant we had working dogs. I knew before speech that the best of them—Border Collies, Kelpies, Blue Heelers—could outsmart many men. All of man’s virtues, with none of his vices as the old saw goes. My parents were also Christian without being doctrinaire (one Catholic, one Protestant, from a generation where “mixed marriages” provoked sectarian disquiet). We kids had been raised to place human beings above animals without thought.

But both agriculture and animal husbandry are older than Christianity. When mum made her remark, she was remembering—at least in a cultural sense—that in agriculture’s prehistory and even post-history, there were working dogs worth more than disabled children.

Emotion Recollected in Anger

This incident came back to me, not in tranquillity, but in response to an internet stooshie. Yes, one of those. I’m old enough to know better than to involve myself, of course, but I’m a lawyer who’s also a classicist and novelist. I’ve written two books set in classical antiquity. Unusually, I’m qualified in both Roman (civilian) and English (common) law. I’ve been paid good money by various outlets (including this one) to translate Roman jurists and write about Roman law.

An internet bunfight about Roman law, literature, and morality? Count me in.

Peter Singer is responsible for a new edition of Roman writer Apuleius’s The Golden Ass. He’s a philosopher, not a classicist, so commissioned a new translation from leading Apuleius scholar Ellen Finkelpearl. And because he’s famous (this is the bloke who wrote Animal Liberation, remember, a book that’s sold nearly a million copies), his publisher pulled out all the stops. Peter Singer’s version of The Golden Ass is a physically lovely object: gorgeously illustrated, printed on acid-free paper (so its pages will never turn yellow), with a fetching matte red dustjacket.

To go with the May publication of the new edition, British classics journal Antigone reproduced a feature Singer wrote for a paywalled outlet (Literary Review) enjoining people to read his version. The piece outlined the decisions he, Finkelpearl, and their publisher made with respect to it, and noted that Singer first read Apuleius (in translation) only seven years ago. He also admitted he’d been unaware that novels existed in antiquity.

Antigone is unpaywalled, and as is often the case with contentious copy made readily available (this is how the Guardian makes its money, after all), Singer’s article proceeded to set the internet ablaze. The academics and schoolteachers who edit and produce Antigone—interested only in encouraging more people to study classical languages and history at school or university—emerged, blinking, not into mere unaccustomed light but a conflagration.

First Came the Classicists…

The blaze took several paths, making firefighting difficult. Classicists (including Finkelpearl, the translator, to be fair) did not like Singer’s abridgment. Apuleius wrote in a literary tradition common to both Greek and Roman antiquity, known in Latin as fabula Milesiaca. “Milesian Tales” were high-end literary pornography, and like Romantic genre fiction now, the Milesian Tale had tight conventions.

Probably the most important was use of a first-person framing device where the narrator then encounters other people who tell various “side stories,” either bawdy or fantastic, interspersed throughout the text. Singer found the framing device—the story of a young, occult-obsessed young man who casts a spell on himself, only to have it go horribly wrong and turn him into a donkey—much more interesting than what he calls “the digressions.” Unfortunately, among the excised digressions is the story of Cupid and Psyche. This is probably the most beautiful of all Roman fairy tales, takes literary form only in Apuleius despite being widespread in Roman culture, and has enjoyed an outsized influence on post-Renaissance literature and art.

The Golden Ass is the only novel from antiquity to come down to us entire, and even then, its survival was idiosyncratic. Saint Augustine hated it with the blazing heat of a thousand suns, spending an inordinate amount of time arguing with his North African literary predecessor in both City of God and personal correspondence. Augustine’s literal cast of mind led him to treat it as memoir, not fiction. He genuinely believed Apuleius turned himself into a donkey by dint of magic and was then returned to human form thanks to the intercession of the Egyptian goddess Isis. This, of course, made pagan Apuleius a member of the Devil’s party even if he did not know it. It also ensured his novel continued to be copied in medieval scriptoria.

Not a few classicists accused Singer of being badly read for coming to Apuleius so late, and the fury over Cupid and Psyche’s absence was profound. However, not all this is Singer’s fault. Although surviving examples are always and everywhere much better written than their modern equivalents (think 50 Shades of Grey), prose was the weak sister of ancient fiction. People who wrote Milesian Tales were considered lightweights.

Neither Greeks nor Romans had an issue with writers of either sex putting their names on plays and poetry. Poets and playwrights—not to mention philosophers, historians, mathematicians, and lawyers—were much higher on the literary totem pole. Those who wrote Milesian Tales, by contrast, sometimes did so under a pseudonym. And this in civilisations that didn’t have modern conceptions of “low” pornography. Porn wasn’t the problem; it was prose wot done it. Here was the Roman world’s version of Silly Novels by Lady Novelists, and those Roman attitudes carried over into later periods. The view that prose fiction was fundamentally unserious persisted until the eighteenth century.

…Followed by the Disabled and the Woke

The niche irritations aired by classicists were as nothing beside the outrage from disabled people (many of whom think Singer wants them dead), followed by Wokies mounting a determined charge from the rear. This was thanks to what attracted Singer to Apuleius’s framing narrative in the first place: its imaginative and sympathetic portrait of an animal, albeit one with a human mind. Apuleius is a fine writer, so he captures the duality of man in an animal body not by the anthropomorphising present in, say, Aesop’s Fables. Instead, he shows a man-donkey-man who enjoys dust baths and suffers split hooves like an ass. Simultaneously, the donkey is not only attracted to mares and jennies like an ass but to human women like a man, which leads to what is probably the only well-written bestiality scene in all literature.

Singer, like Augustine, has a literal cast of mind. Although he doesn’t mistake novels for memoirs, he does assume Apuleius the writer wants readers to sympathise with animals, even to think they may have something approaching interests, if not rights. He seems to think Apuleius wrote as he did to serve an ideological purpose and attempts to persuade us this is true by imputing the views held by invented characters to the author. Even the most political of novelists don’t do this. Emmanuel Goldstein is not a stand-in for George Orwell. This forgets that the purpose of writing novels is to gain imaginative entry to the minds of fictive characters which resemble neither writer nor reader. Fail in this, and no-one will read what you write.

Because Singer engages in moral ranking that—as my mother once did—sometimes places animals above man, his claims for Apuleius’s brilliantly crafted donkey-man-character are enraging for the same reason that his wider philosophy is enraging. He believes, for example, that human life is not necessarily more sacred than canine life, and that any animal (including a human animal) with no hope of becoming self-aware has no hope of becoming what he considers “a person.” Human infants, meanwhile, are not yet persons, and in the case of some disabled infants, may never become so. If a baby is severely disabled and the parents prefer to kill it, he thinks this should be permitted. When it comes to our fellow-creatures, what matters most is not whether an animal can reason or talk but whether it can suffer, which is what makes him both a staunch and effective advocate for vegetarian and vegan diets.

While the rage directed at Antigone came from Wokies as much as disabled people, only the fact of the publication being scooped up alongside one of its writers is wholly woke: guilt-by-association is that political movement’s stock-in-trade. Separately from wokery, Singer has been a target for disability activists for decades, especially in Germany. While researching this piece, I found references to anti-Singer protests occurring there when I was in primary school. In the 1980s. For Germans, the unpleasant resonances are historical. The Nazis targeted disabled people (considered Lebensunwertes Leben, “life unworthy of life”) before they went after Jews and Gypsies. They were first to be marked out for mass killings, and first to be gassed on German soil.

However, the dispute over Singer’s version of The Golden Ass, and Apuleius’s sympathetic portrait of animal suffering, pulls on a different historical thread. One with origins in Roman law.

The Law of Animals

The planet’s two great legal systems developed in two European civilisations, Rome and England. Their wide provenance is not only due to both peoples conquering great empires. It’s also because they worked: they did things no other legal regime did before them, and those others are still incapable of doing now. And not just high-minded things like the presumption of innocence or the rule of law. Things like consumer protection (which, somewhat nauseatingly, has roots in the Roman law of slavery), limited liability, commercial loans, maritime law, the law of trusts, remedies that take the form of performance as well as damages. Incredibly, these developed independently of each other. The English common law did not borrow from Rome: when it first emerged, Roman law was lost.

This meant both traditions produced laws around animals—especially, given the importance of agriculture and animal husbandry—liability for the damage animals can cause. Singer makes much of the fact that pagan Romans had no doctrine of special creation, and while Roman law drew a firm line between human capacities for reason and speech and their absence among animals, it recognised man was also an animal. Roman philosophers like Lucretius and Roman jurists like Gaius and Ulpian were much closer to Charles Darwin than what came after, until, of course, Darwin himself. This means ancient Roman animal law looks much like modern animal law. At no point is it supernatural or does it imbue animals with capacities they do not have. Liability is carefully and sensibly worked out using reasoning familiar to every lawyer.

However, as Professors Katy Barnett and Jeremy Gans reveal in their forthcoming book, Guilty Pigs: the Weird and Wonderful History of Animal Law—despite the Christian doctrine of special creation—animals were later saddled with both criminal and civil responsibility and assumed to have the ability to form intent. “Pigs, cows and other domestic animals were put on trial for murder and other crimes in late medieval and early modern Western Europe, particularly in France. Writs were served on weevils, rats and other vermin, abjuring them to leave an area upon pain of anathematisation,” Barnett told me.

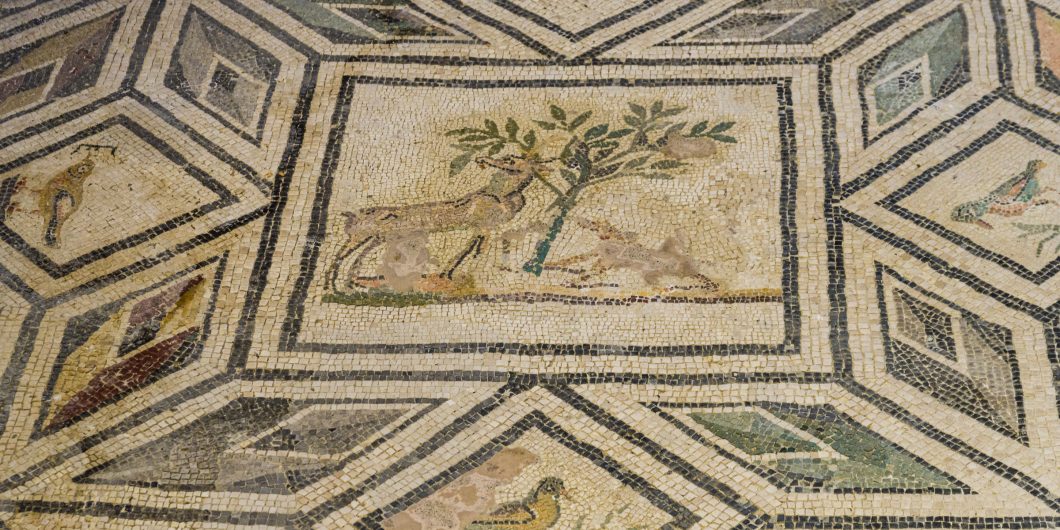

Even more incredibly, Barnett describes how “this was bolted onto pre-existing Roman law in civilian countries; it didn’t emerge at all in England, where animals were treated as analogous to things.” Roman legal arguments categorising animals alongside children and slaves were blended with Biblical and Talmudic laws on goring oxen (where animals could be prosecuted), then added to Canon law, producing frankly bizarre trials. The cover design for Guilty Pigs is based on a fresco from the church of Sainte-Trinité in Falaise—unfortunately painted over in 1820—depicting a pig in the dock, on trial with defence, prosecution, witnesses, judges, bailiffs, the lot.

Reaching back to a morally different past may be excellent education but not necessarily excellent guidance.

As he isn’t a classicist, Singer also isn’t a lawyer, which means he probably doesn’t know this idiosyncratic legal history (and should read Guilty Pigs when it’s published next year). Relatedly, we (and he) now have a problem. Here is a philosopher notorious for ranking animals above humans—at least some of the time—paying admiring obeisance to a legal system that was not only superior as law to what came after, but which also (and notoriously) ranked incapable humans with unwanted animals. Roman law permitted killing both animals and humans for sport (the jurist Gaius even provides specimen clauses for gladiator hire-purchase contracts) while encouraging parents to kill disabled children. It was, in modern terms, eugenicist. True, Roman eugenics differed from Spartan eugenics in that the decision was left to parents and not mandated at the state’s behest, but the distinction is one of degree, not kind.

When I came to write Kingdom of the Wicked, a novel imagining what the world would look like if the Romans had undergone an industrial revolution (while retaining their pre-Christian morality), I had to grapple with the issues Barnett and Gans raise. It meant, for example, writing a scene where an admirable Roman advocate loses his lunch when he first meets a particular client. The reason? The Jewish parents he’s acting for have kept their spina bifida-afflicted son alive. So seldom is this done at home, he doesn’t even know whether the child is human. After Kingdom of the Wicked was published—when I had to explain this scene (and others like it) to interviewers in Australia and the UK who knew nothing of Roman law—I said things like, “basically, they had Peter Singer laws.”

Who Counts?

I’m happy with anything that makes both Latin literature and Roman law better known, especially outside the civilian countries that are now the latter’s natural home. I’m not going to get a bug in my hat about the absence of Cupid and Psyche. Relatedly, I think the people who went after Antigone because they don’t like one of the writers it published need to get better hobbies.

That said, both Apuleius’s The Golden Ass and Peter Singer’s gloss on it are reminders that different societies (and individuals) can hold different logically coherent ethical frameworks because they prioritise different values. Maybe they even have different conceptions of those values. “Freedom” means different things in different countries and cultures, for example. In America the right to own a firearm is a core component of liberty, in Britain it isn’t. In Britain there’s strong resistance to ID cards (whence the current contretemps over vaccine passports) and banning items of clothing. Meanwhile, in France ID cards are accepted, and niqabs are illegal. I’ve had to argue in this magazine that France is also a liberal polity: not all liberalism is based on Anglophone-style state neutrality in the face of competing conceptions of the good.

I’m not making an argument for moral relativism here. I think there are better and worse moral systems, and better and worse cultures. What I am arguing for is value pluralism, and against the notion that ethical decision-making is a relatively straightforward calculation between comparable goods. Legal practice taught me that most people have several sets of value-scales and if you ask them to set those scales off against each other the response will be something like the moral dumbfounding I experienced as a child. For that reason, I don’t think it’s possible to rank goods on a scale reducible to a single super-value like utility or happiness.

The moral contrasts between us and the Romans represent value shifts over time. Reaching back to a morally different past may be excellent education but not necessarily excellent guidance. On this point, the man who taught me jurisprudence at Oxford, Professor John Gardner, used to quip, “when you want to know if something is cruel, don’t ask a moral philosopher.”

We can learn a great deal from Ancient Greece and Rome without promoting them as cultures that any sane person should seek to emulate. The study of Roman law forces us to confront hard questions like, given people are factually unequal, how do we uphold the rule of law? Reading both Roman jurists and writers like Apuleius is to be reminded that one legal principle taught to generations of law students—often in their first lecture—remains as true as ever. There is no necessary connection between law and morality. Of course, there can be. But don’t bet the farm on it.