In cutting by half the funding to Palestinian refugees, President Trump has made a significant action that other Republican Presidents did not.

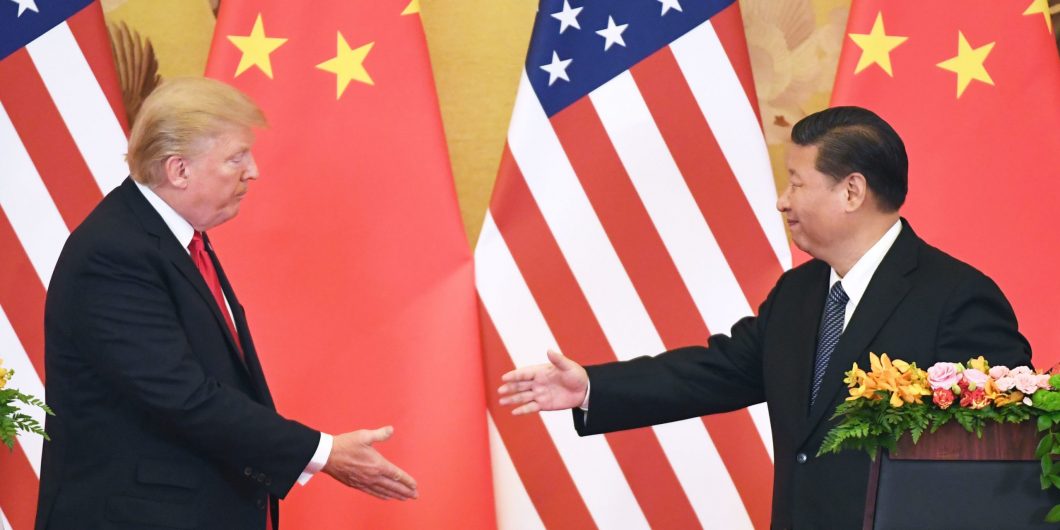

Divorcing from China?

What is the proper role of commercial relations in the Sino-American geopolitical competition? Should Washington do anything to economically strengthen the most complicated and challenging rival it has ever faced? Thus far policymakers have avoided this most fundamental of strategic questions. But a well-considered answer would help clarify much of the confusion that bedevils the current China policy debate.

The United States is gradually moving from a China policy of “engagement,” animated by the idea that China could be tamed and “socialized” into becoming a “responsible stakeholder” in an American-made international order to one of competition and confrontation. Economic enmeshment was the key to the engagement policy. But that is changing.

Donald Trump, who has done more to change the conversation about China than any president since Richard Nixon is driving this new approach. As the authors Bob Davis and Lingling Wei show in their well-reported and fascinating look into Sino-American economic relations, Superpower Showdown: How the Battle Between Trump and Xi Threatens a New Cold War, Trump acted on concerns that previous administrations had only intermittently addressed.

The list of grievances—debilitating intellectual property theft, currency devaluations to favor Chinese exporters, mass subsidization of state-owned companies—is long. Not known for his subtlety, Trump confronted China with the bluntest of tools: tariffs. Before 2016, the idea of imposing across the board tariffs on China would get one excommunicated from most think tanks, presidential administrations, and congressional offices. But we now have grown accustomed to them. Even if Trump loses his re-election bid in November, it is unlikely that a President Biden would lift all the tariffs on China.

Not only did Trump use tariffs, but his administration has tightened export restrictions on high-technology goods, strengthened investment restrictions on Chinese companies, and levied criminal and civil charges against Chinese technology giant Huawei for sanction violations, bank fraud, and trade theft. The case is ongoing, but the US has officially banned tech sales to the Chinese malfeasant tech company. These legal and administrative actions against Huawei have been accompanied by a diplomatic campaign meant to convince allies to reject the tech colossus’s equipment from international telecommunications networks.

But still, as Davis and Wei chronicle, the Trump administration has not asked or answered the fundamental question about trading with a rival: what do we want out of our trade relations with the Middle Kingdom? This question is not trivial. China was the largest US trading partner (in terms of goods), the third-largest US export market, the largest source of US imports, and had a $380.8 billion trade surplus with the United States in 2018. The US benefits from trade with China, and will benefit more if China returns to market reforms.

Perhaps for the president the answer regarding the future of Sino-American economic relations is simple enough. He campaigned on reversing trade deficits and on redressing China’s unfair trade practices. A “win” for him would be massive new US exports into China (and an accompanying supercharching of the stock market).

But some of his savvier trade negotiators and national security officials want more. The most compelling parts of the book report on what the negotiators and policymakers on both sides were thinking before striking a deal in January 2020. The authors provide a detailed account of the negotiations that failed in April and May 2019. As the authors write:

US tariffs hurt China more than its leader, Xi Jinping, publicly acknowledge. Electronic exporters in Dongguan and other coastal cities were losing American customers… Both government-controlled and privately owned businesses were delaying or cancelling investment plans. Big US companies were accelerating their decisions to move production from China to Vietnam, Malaysia, and other countries far from the trade war.

The US team sensed this and pushed a “150 page agreement covering many American complaints against China: technology transfer, weak intellectual property, protection, closed financial services market, currency devaluation. Each chapter of the document had specific laws and regulations that China had to amend.”

Chief trade negotiator Robert Lighthizer, a seasoned trade lawyer with years of experience suing China on behalf of steel companies and other clients knew what he was doing. He wanted to settle for no less than a systemic reform of the Chinese economic system, akin to what president Bill Clinton’s team had asked for and Chinese reformers Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin, and Zhu Rongji had accomplished to prepare China for the World Trade Organization. But since that time China had taken a great leap backward economically. The state sector roared back to dominate the Chinese economy. State subsidies to state-owned enterprises (SOEs) dominate the economy and distort domestic and global markets.

What the American negotiators did not know is how constricted Xi had become politically, contrary to his all-powerful public image:

Xi had angered so many senior party officials, bureaucrats, and influential former officials with his anticorruption drive that he had enemies waiting to take him down a notch.

China’s paramount leader could not afford to be seen as weak in dealing with the US. And Xi had also misread Trump’s United States. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) read too much into the president’s hectoring of Fed Chairman Jerome Powell. Xi thought American allies, who were furious with Washington over tariffs targeting them, would be on his side of the Sino-American dispute. His view of US isolation was reinforced when 40 heads of state and government ignored a U.S. boycott and attended an April 2019 conference on the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Thus China crossed out most of the IP section in the 150 page document including requirements to change laws, and would not address currency devaluation. At the time, China faced 25 percent tariffs on $50 billion worth of goods and 10 percent on another $200 billion. Xi and the senior leadership wanted to keep a dialogue going so that China can be seen to be a “responsible party”—even as Trump levied 25 percent tariffs on the remaining $300 billion worth of goods exported to the US.

Certainly de-coupling from China poses a big problem if Washington doesn’t open other big markets. But the authors may overstate the importance of trade with China for the US. The American economy was still growing fast before COVID. Moreover, no one is filing for a full economic divorce.

The authors report, not completely accurately, that the breakdown in talks allowed national security hawks such as then-National Security Advisor John Bolton to implement a plan to rattle Beijing, by crippling Huawei among other actions, for example. Indeed, as Huawei faced criminal and civil legal actions, the US put it on an “entity list” at the Department of Commerce, severely restricting US companies sales to it (semiconductors, other components). A May 15, 2019 Executive Order targeted Huawei for violating sanctions on Iran and other “actions counter to US interests.” It is true that Bolton and his NSC team had a plan for economic and national security pushback once the trade talks failed. But his predecessor, H.R. McMaster, was no less hawkish. He oversaw the crafting of the 2017 US National Security Strategy (NSS). By Washington DC policy standards, the NSS was revolutionary in identifying China as a revisionist power and a strategic competitor for two reasons. First, since 9/11 the Middle East and then Russia had pre-occupied the foreign policy cognoscenti’s attention. Second, it is rare for a consensus national security document to describe a threat in such stark terms, particularly if it is a major trading partner.

The vast US bureaucracy already had started to shift, however gradually and fitfully, to ready itself for a strategic competition with China. For example, the US military is prioritizing the Indo-Pacific and upped its challenges to China’s territorial ambitions in the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait.

Eventually the two sides reached a modest trade deal. But then came COVID-19. The fury of the US at China’s malfeasance during the pandemic resulted in a much tougher China policy, from sanctions against the PRC for human rights abuses in Xinjiang to a crackdown on Chinese malign influence in the US. This has been a tough year for Sino-American relations.

What about the biggest question: where will all this leave us with respect to trading with China? According to the authors, Trump is both a “hawk and dove” on economic issues. He wants to change China’s policies but not rattle global markets. The authors think the US is too dependent on China to “de-couple” from its economic relations with China. Certainly de-coupling from China poses a big problem if Washington doesn’t open other big markets. But the authors may overstate the importance of trade with China for the US. The American economy was still growing fast before COVID. Moreover, no one is filing for a full economic divorce. Rather, the US is blocking the acquisition by the PRC of the most cutting-edge technologies that have military applications. That should not be overly burdensome.

And would US national security policy be served if the economic team got what it wanted from China on economics? In such a scenario, China would undergo “structural reform” again—less subsidization and market manipulation and a stronger IP regime would be the result. At first glance, the answer appears simple: of course the US would welcome such a change. Global growth would be higher, and US companies and workers would prosper as well.

But a more economically vibrant China would still compete with the US over who is the prime power in global affairs and who gets to shape the 21st century global order. If the US got what it wanted economically, China would likely be a more wily and enduring competitor. This dilemma illustrates why, contrary to the authors’ argument, the US and China are not in a “Cold War”—a war that doesn’t involve actual shooting. They still want to trade which means mutual benefit. Indeed, the very purposes of a strategy of competition should be to illustrate to the CCP that it cannot prevail in its more nefarious purposes. US strategy would try to make unattractive all other options besides returning to open-market policies which benefit both countries. That is a far more complicated strategic task then anything the US faced in the Cold War.