A Strategy for Fiscal Discipline

Recent debates in Washington on the debt ceiling and on the mandatory expiration of all federal legislation have made one thing clear: in the very near future, federal politicians will need to find a way to reverse more than a half-century of expanding government. While there are natural limits on how intrusive and confiscatory a democratic government can be—witness the turmoil in today’s France resulting from tussles over its gigantic state—the American public will demand change before that. Experience elsewhere shows that inescapable and formal rules that limit government are the only way forward.

Frustration that the American public sector is too large and needs to be constrained more effectively has been a major driving motivation of conservatives for decades. But they have placed their faith in energetic political movements and philosophical appeals to liberty. In a country whose population increasingly mirrors those of other social welfare Leviathans, such approaches have failed. We may pride ourselves on the fact that only 38% of spending in our economy this year will come from governments at various levels, compared to 58% in France, according to International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecasts. But the evidence shows we are merely lagging behind France, not avoiding its path. For every Tea Party, there are three Green New Deals.

Countries like the United States with large federal legislatures tend to have more out-of-control governments, according to work by Beatriz Maldonado of the College of Charleston. But changing our constitution with, say, a smaller House of Representatives or a constitutional amendment to limit the size of government, are non-starters because of the high bar for constitutional amendments. Switzerland put a balanced budget into its constitution in 2003 via a popular referendum. But in the US, where most of the population pays little or no income taxes and thus thinks that it benefits from government excess, there is no chance of doing likewise. Formal rules are the last hope.

Formal rules differ from the usual prescriptions to control government because they limit the gas in the tank, rather than the number of planned road trips. If we cannot prevent politicians from devising ever-more plans for government action, we can at least deny them the means to put them into effect.

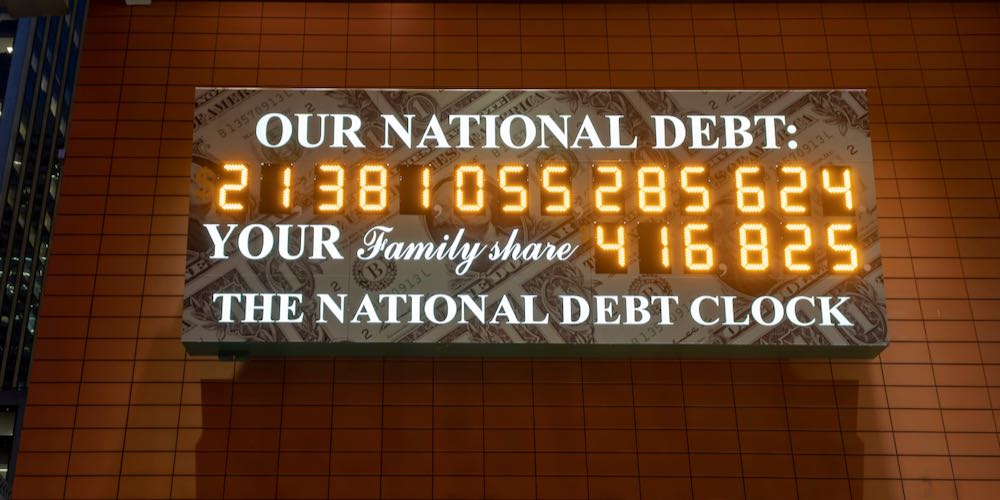

Fiscal rules are the most urgent need because there are too many lenders in the world eager to park their savings in US treasury bonds. That means we are addicted to deficits, which places burdens on current generations with rising interest payments and on future generations with the principal. Such rules commit politicians to follow a fixed formula for balanced budgets, reserves, and debt levels, giving them plausible deniability with voters when spending is cut. They can even extend limits on the size of certain spending items.

Sweden and Germany are two countries where fiscal rules have worked. When Sweden’s public debt peaked at the equivalent of 69% of GDP in 1996, the country got serious. The legislature passed rules mandating an annual budget surplus of 2% of GDP (later reduced to 1%) that could be softened only to a balanced budget in times of recession. The only item excluded was interest on the public debt.

No major country has brought its fiscal house in order without mandatory rules, and it seems only a matter of time before US politicians are forced to follow their peers in other countries.

Sweden tackled entitlements via four means: making them more efficient by cutting waste; reconfiguring pensions into a defined contribution rather than a defined benefit system, alongside partial privatization; automatic cuts to pension payments when the economy is in recession; and directing all of the budget surpluses into those same programs to cushion them from the effects of cuts.

Sweden also created an autonomous Fiscal Policy Council, a fiscal equivalent of our Federal Reserve, to make the hard choices that politicians feared. The council removed so-called “fiscal alchemy” from the public debate when politicians lie to the public about the fiscal effects of their policies. The whole package worked miraculously. This year, Sweden’s public debt will be the equivalent of just 31% of GDP, according to the IMF.

The German fiscal rules were messier because of the country’s federal structure and because they were tied to European Union guidelines. But the results were similar. After peaking at the equivalent of 82% of GDP in 2010, Germany’s public debt will fall to 68% this year.

Why haven’t fiscal rules—like the debt ceiling or various balanced budget amendments—worked in the United States, where public debt will reach 123% of GDP this year? In a word, because they have been ignored. As a Congressional Budget Office report of 2020 showed, fiscal rules work only when they cannot be gamed or amended and when they cover the biggest drivers of deficits, in our case Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security. The IMF recommends mandatory triggers to cut spending on pensions and healthcare when it exceeds forecast projections in the absence of revenue increases, a blunt instrument that, when wielded credibly, will force politicians to make decisions to keep the programs solvent. No major country has brought its fiscal house in order without mandatory rules, and it seems only a matter of time before US politicians are forced to follow their peers in other countries.

Fiscal rules are not enough, however. Governments also constrain liberty and crowd out civil society by over-using their regulatory and administrative powers. These gas tanks also need to be siphoned off. President Biden’s litany of petty new regulations promised in his 2023 State of the Union address shows the threat from red tape as well as red ink.

The number of new pages published in the federal government’s record of all regulations, the Federal Register, was just 17,000 per year in 1960 but rose to 76,000 per year in the 2010s. Now the figure is above 80,000 per year, or one new page every seven minutes. The Competitive Enterprise Institute estimates that federal regulations cost the equivalent of 8% of GDP in 2021. This is almost certainly an underestimate because firms shift into less productive activities in the face of regulatory burdens. The IMF, for instance, estimates that the costs of the 2010 Dodd-Frank banking law amounted to a 0.41% tax on bank profits as banks avoided heavier regulation by sizing down.

Add in state-level regulations, and you have a sclerotic economy burdened down by dumb ideas that do not achieve anything. Rules governing, say, mergers and acquisitions, banking regulation, and methane emissions from new oil and gas wells have been subject to constant change since the Obama days.

Some regulations may deliver benefits that justify the costs. But most federal and state regulations have no in-built processes to determine whether they are working as intended or are worthwhile. Many regulations are so badly written or impractical that companies take calculated compliance risks to ignore them, which in turn creates an industry of litigation lawyers. While well-intentioned, the 1995 Paperwork Reduction Act often displaced paperwork burdens to other forms. The federal regulation created in 1981 on the use of human subjects in research failed from the start but did not get simplified until 2017, more than a decade after the first bottom-up efforts to demand change.

While sometimes welcome, government intrusion can replace the pluralism of private information with centralized Groupthink.

The OECD encourages member states to adopt rules against a “regulate first” mentality in favor of a “reflect first” mentality that considers other options. It also advises mandatory evaluations of all regulations two years after implementation, the topic of a recent tussle in Washington over the “sunset” of all laws. South Korea sunsets all laws and regulations, meaning they expire unless explicitly renewed. Another idea is “regulatory offsets” that eliminate old regulations when new ones are created, usually “one in, one out.” President Trump’s “one in, two out” was a bold stroke overturned by Biden’s regulatory-happy administration.

Rules controlling other types of government sprawl are more tricky. In an era of big data, the federal government has followed its counterparts elsewhere to provide new forms of information like college scorecard rankings, certified federal contractor lists, stress tests for major financial institutions, or, notoriously, infographics on “whiteness.” While sometimes welcome, government intrusion can replace the pluralism of private information with centralized Groupthink.

The dangers of federal informational overreach in banking were apparent during COVID when stress-test results were issued that experts argued did not reflect the depth of the crisis. Yet, as with regulations, there are no mandatory rules to evaluate when government information does more harm than good.

Finally, the proliferation of new government institutions, an ever-expanding list of agencies, directorates, commands, and commissions, as well as expanded roles for existing ones, is desperately in need of rules-based governance. Just as government spending, regulation, and data need a rules-based diet, so do government staff and organizations. An easy start: ban public sector unions, which bloat staff numbers and benefits and stymie private outsourcing. No less important, follow best practices in other advanced industrial economies and routinely terminate unnecessary government agencies. Does anyone miss the federal Office of Noise Abatement and Control?

The US is behind other rich countries in confronting the need for fiscal rules to control government. But there’s no need to stop there if we want to protect a free republic of citizens rather than bureaucrats.