What would an action program renouncing ethnic categories and embracing individualistic liberalism look like?

After the Blaine Era

Since 2017, three US Supreme Court decisions have put to death the so-called Blaine Amendments found in 37 state constitutions. These Amendments prohibit states from using public funds to provide financial aid to religious institutions, including K-12 religious schools. Under the guise of “separation of church and state,” they have been the most common legal means used to thwart school choice programs that include religious schools. The Amendments were named after Republican James G. Blaine of Maine, who served in the US House of Representatives and Senate as well as in the administrations of three presidents.

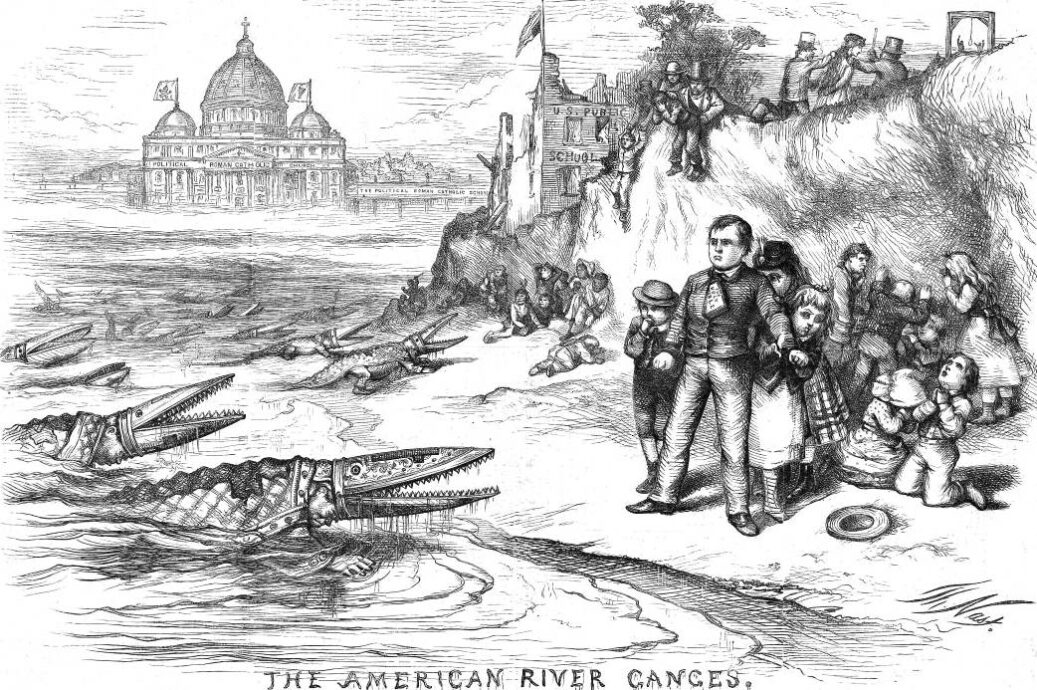

In 1875, Congressman Blaine, who was then Speaker of the US House of Representatives, tried to amend the US Constitution to outlaw direct government aid to educational institutions with a religious affiliation. His aims revealed both nineteenth-century anti-Catholic bigotry and nativist tendencies hostile to immigrants: the amendments especially targeted Catholic schools that served large immigrant populations. That effort failed. But his idea was adopted by state legislators, who added provisions to state constitutions that accomplished what Blaine could not achieve nationally.

For decades, these legislative ghosts of nineteenth-century prejudices continued to haunt efforts to bring greater educational freedom to American families. Thankfully, the “slow motion execution” of the Blaine Amendments began in 2017 with the Supreme Court case Trinity Lutheran v. Comer. State officials in Missouri had denied the benefit of state funding to the Trinity Lutheran Church Child Learning Center preschool program in Columbia, Missouri for a playground resurfacing program due to the state’s Blaine Amendment.

The Court ruled 7 to 2 that this was unconstitutional because it violated the free exercise of religion clause of the First Amendment. In that decision, the Court introduced a distinction in Footnote 3 between a benefit based on an institution’s status or identity and one based on an individual’s use or conduct. In other words, Missouri could not deny a public benefit to an otherwise eligible institutional recipient solely on account of its religious status or identity.

The potential effect of this distinction was summarized by Institute for Justice senior attorney Michael Bindas. The footnote suggested that “although the government may not withhold a benefit based on the would-be-beneficiary’s religious status, or identity, it may withhold a benefit based on the religious use to which the would-be-beneficiary might be put. [This suggests a state constitution] could still bar a family from putting their educational-choice benefit to the use of procuring a religious education.”

The effect of this is to suggest that the Blaine Amendments concern both religious status and use. In Trinity Lutheran, the Court ruled that it is unconstitutional to withhold a benefit based on status. This was an important step towards overturning the Blaine Amendments, but a decision regarding the constitutionality of allowing public dollars to be put to a religious use—for example, religious instruction—would live to see another day.

The next step on the road to slaying the Blaine Amendments was Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, decided in 2020. In 2015, the state of Montana passed a tax-credit scholarship program for individuals and businesses who contributed to non-profit scholarship organizations that provide financial assistance to low-income families to pay for private schools. But the Montana Department of Revenue promulgated an administrative rule prohibiting scholarship recipients from using scholarships at religious schools, citing the state’s Blaine Amendment.

In a 5 to 4 decision, the US Supreme Court ruled that this prohibition violated the free exercise of religion clause of the First Amendment. As with Trinity Lutheran, the state’s rule discriminated against religious schools and the individual families whose children might attend them based on their religious status. In the words of Supreme Court Justice John Roberts, “A state need not subsidize private education [but] once a State decides to do so, it cannot disqualify some private schools solely because they are religious.”

The judicial death knell for the Blaine Amendments came in 2022 with Carson v. Macon. This case involved the state of Maine, which did not have a Blaine Amendment. But it did have a law codified in 1981 that excludes religious schools from a tuition program enacted in 1873 that pays for students to attend private high schools (since many rural communities in Maine do not have high schools at all). Prior to 1981, the tuition program was used to send children to religious schools. The US Court of Appeals for the First Circuit ruled that the state’s tuition program—which could be used at religiously affiliated schools, but only if they did not proscribe religious instruction—was constitutional because it discriminated based on religious use and not status.

However, the US Supreme Court ruled 6 to 3 that this approach was unconstitutional because its use-based distinction was equivalent to religious discrimination. Justice Roberts wrote, “The State pays tuition for certain students at private schools—so long as the schools are not religious. That is discrimination against religion [as it] exclude[s] some members of the community from an otherwise generally available public benefit because of their religious exercise.”

So as Trinity and Espinoza were about discrimination on the basis of status and Carson was about discrimination on the basis of use, the Court put the nail in the coffin of the Blaine Amendments. Carson “killed the status/use distinction [and] the Blaine Amendments,” writes Institute for Justice’s Michael Bindas, because it removed “the most significant legal cloud that remained over educational-choice programs: the constitutionality of state bars to religious options.”

Proponents of educational freedom can rejoice that the long battle to overcome the Blaine Amendments has been won along with another step on the path to First Amendment pluralism.

The landscape for educational freedom is thus finally freed of nineteenth-century prejudices. But other federal constitutional questions remain.

For example, immediately following the Carson decision, Maine Attorney General Aaron Frey released a statement decrying the decision. “The education provided by the schools at issue here is inimical to a public education. They promote a single religion to the exclusion of all others, refuse to admit gay and transgender children, and openly discriminate in hiring teachers and staff. I intend to … ensure that public money is not used to promote discrimination, intolerance, and bigotry.” He vowed to do all within his power to ensure that the Maine Human Rights Act banning discrimination against someone because of their race, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity or disability would be enforced since the Court’s decision does not make it clear whether “any religious schools that accept public funds must comply with anti-discrimination provisions.” This would mean that religious schools with policies that discriminate against students and staff for any of those reasons would be prevented from participating in the Maine tuition program. (Of course, federal law currently prohibits all private schools, whether or not they participate in educational choice programs, from discriminating based on race or ethnicity.) But Nick Reaves, counsel at the Becket Fund, writes in the Harvard Journal of Law that since the Court in Carson relies on “the principles of religious autonomy, [the Court] confirmed that religious organizations must have the freedom to operate in accordance with their beliefs.” The Supreme Court will eventually decide this issue.

Another unresolved question is whether states with secular public charter school laws can allow religious private charter schools. Charter schools are privately operated but publicly funded institutions that are defined in state laws to be public schools. The answer depends on a legal concept named the state action doctrine which requires that there be state action—not merely private action—before there can be a constitutional violation. If for federal constitutional purposes charter schools “are private then … prohibitions on charter schools being religious are unconstitutional. But if they are public ‘state actors’ then [charter schools] likely [must] be secular,” writes Notre Dame Law Professor Nicolle Stelle Garnett.

This issue has sharply divided elements of the school choice movement. Some like Professor Garnett argue that charter schools are not state actors for federal constitutional purposes and are “programs of private school choice.” Others like the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools strongly disagree, arguing “Charter schools are public schools and are state actors for the purposes of protecting students’ federal constitutional rights.”

The US Supreme Court had an opportunity to accept a North Carolina case that raised questions about students’ constitutional rights in a public charter school under the federal equal protection clause. The school’s founder argued the school could enforce its specific dress code requirements barring girls from wearing slacks or shorts because it operates as a private institution with public funding. The 4th Circuit of Appeals in a 101-page ruling rejected that argument in a 10 to 6 ruling saying that the public charter school is a state actor. Attorneys general in 10 GOP-controlled states had urged the Supreme Court to consider the case. The Supreme Court asked the Biden administration to weigh in on a pending appeal. The administration, in filings, urged the justices to pass on the case. The Court declined to take up the case, leaving the state actor decision until another day, which seems to be coming the Court’s way by way of Oklahoma.

Authorities in Oklahoma approved plans for an online or virtual religious charter school that would be paid for using taxpayer dollars (like all other charter schools) and run by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Oklahoma City and the Diocese of Tulsa. This approval was based on a 15-page single-spaced advisory opinion of Oklahoma Republican Attorney General John M. O’Connor’s legal interpretation of Trinity Lutheran, Espinoza, and Carson decisions. O’Connor was succeeded by Republican Gentner Drummond in January 2023 who proceeded to withdraw his predecessor’s opinion. He filed a lawsuit against the State Virtual Charter School Board that approved the school arguing that charter schools are state actors and therefore must be secular. None of the three cases discussed above clearly resolve this issue.

A final example involves the so-called public/private Blaine Amendments that are found in some states. These ban aid to all private schools, whether religious or nonreligious. For example, the Alaska constitution’s Article VII Section 1 on Public Education states, “No money shall be paid from public funds for the direct benefit of any religious or other private educational institutions.” Most state courts have interpreted these laws as barring aid to schools and not to students who attend private schools. But a few state courts—like those in Alaska, Hawaii, and Massachusetts—have been more restrictive and do not allow programs that aid students. In light of these recent Supreme Court decisions, those laws may now be challenged.

The broader debate concerning the use of taxpayer dollars to support school choice programs that include religious schools will continue. But proponents of educational freedom can rejoice that the long battle to overcome the Blaine Amendments has been won along with another step on the path to First Amendment pluralism.