More than first in war, peace, and in his countrymen's hearts, George Washington was also first in business in America.

A Nation of Transcendental Hustlers

We are living in fraught times, as the very origins and destinies of America are controverted and convoluted. The 1619 Project tells us that slavery is the corrupt root from which the American tree of so-called liberty has grown. Various other initiatives offered with more or less sincerity—such as the National Association of Scholar’s 1620 Project, The Federalist’s 1620 Project, and the presidential 1776 Commission—challenge this revisionist origin story. Against this backdrop Lance Morrow’s God and Mammon: Chronicles of American Money offers a timely and lively retrospective of the motives, passions, and interests of American experiments in ordered liberty and misadventures in disordered license.

As Morrow describes it, the book is about money and slavery: “The triumphs of American money have been great. I talk also about its failures and limitations—and about values that lie beyond money’s capacity to measure, meanings that cannot be grasped in money’s language.” So too does Morrow focus on slavery and its historical legacy: “the book is about a theological error—an evil, slavery—introduced an eon ago, when America was a garden, and about how to evaluate that long-ago sin and its effect upon the country now.” These twin concerns emerge from the shadow of the coronavirus pandemic and social unrest in the United States, and Morrow provides an exploration of all these earthly matters with at least a nod to the eternal. Both money and slavery have theological dimensions that Morrow not only acknowledges but also interrogates well.

A Noble Mythos

There is a kind of mythology going back to the American founding and before emphasizing—if not absolutizing—the noble causes of “liberty and justice for all,” as the Pledge of Allegiance puts it, and the “unalienable Rights” of “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness,” as we read in the Declaration of Independence. Like any powerful mythos, this perspective gets at some deep and fundament truths, perhaps even the most significant truths about America. But if the founders were wise enough to substitute “Happiness” for “property” from the Lockean trinity of political economy, the grinding necessity of material provision has never been and never will be excised from human society—at least this side of the eschaton.

Take, for instance, the Pilgrims and the Mayflower Compact, whose 400th anniversary is one of the things to celebrate in 2020. The Pilgrim Fathers sought religious liberty and saw the New World as a land of opportunity to freely exercise their sacred rights of conscience. These same colonists had already spent a decade as refugees in the Netherlands, where they could worship freely. What they could not do in Amsterdam and later Leiden, however, was find enough economic opportunity and political security to adequately support their growing community. Virginia (where they hoped to end up) offered enough space for flourishing out of the practical reach of establishment England as well as Catholic Spain. For the Pilgrims, America was thus a land of opportunity not only for spiritual matters but material as well, and this dialectic of eternal and temporal concerns has defined the American experience through the centuries. In this way, the Pilgrims were among the first great enterprisers in the New World. Morrow writes that he has “entertained the notion that Americans themselves are essentially essayists—attempters—and that the country is an essay in history and ethics, a probing forward through time.”

At its best this dynamic between spiritual and economic liberty has led to moral as well as material success. As Morrow aptly observes, “In 1702, Cotton Mather preached that the Christian must row to heaven with two oars—the oar of his spiritual calling and the oar of his material calling. If he pulls on only one of them, the boat goes in circles and the Christian can never reach the safe harbor of salvation.” To continue the metaphor a bit, the stronger arm of material interests constantly pulls us off course, however, and material prosperity tends to blind us to eternal truths. Keeping both oars in the water is hard work, and a matter of ascetic discipline. “The nation’s founding Christianity,” writes Morrow, “was burdened—even embarrassed—by Christ’s preference for the very poor and abhorrence of the rich. It was the poor who would inherit the Kingdom of Heaven.” That sentiment drawn from the Sermon on the Mount is worth returning to, but in the meantime we should appreciate the scope of Morrow’s enterprise.

The theological significance of money and slavery are leitmotifs of Morrow’s study, and sociology figures just as prominently in his analysis as does economics or politics. Morrow opens with this keen insight from Tocqueville: “One usually finds that love of money is either the chief or a secondary motive at the bottom of everything the Americans do…. It agitates their minds but disciplines their lives.” Morrow wisely avoids reference to the famous Weber thesis, and he thankfully refers to Calvinism not in predestinarian terms but as a representation of American consciousness of sin. Calvinists, puritans, and pilgrims might well prosper materially, but this wealth would not substitute for sanctification.

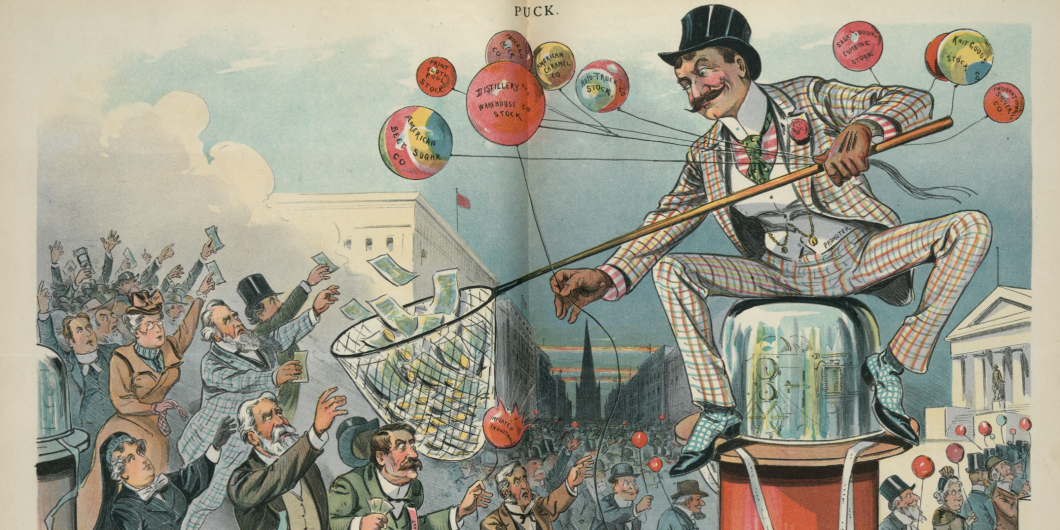

If the biblical Exodus narrative forms an important image for American self-understanding, then the pattern of prosperity, idolatry, and judgment in the Hebrew scriptures likewise applies to American history. In his own time, writes Morrow, Cotton Mather “fretted that money had already gotten the upper hand. He wrote: ‘Religion brought forth prosperity, and the daughter destroyed the mother… there is danger lest the enchantments of this world make them forget their errand into the wilderness.’” The biblical cycle of divine blessings and prosperity preceding a turn to idolatry, sinfulness, and decadence was already beginning in the New World. Rather than being viewed as a divinely ordained means to serve God and one another, money became an end in itself.

“I love America more than any other country in this world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.”

James Baldwin

A recent pop culture artifact can be called as a witness. Lana Del Ray’s 2015 song “National Anthem” plays on the Kennedys, Camelot, and 20th-century Americana to illustrate one facet of the truth about our nation: “Money is the anthem of success / Money is the reason we exist / Everybody knows it, it’s a fact / Kiss, kiss.” It was, in fact, just about the time of JFK’s ascension to the presidency that John Kenneth Galbraith was describing the “mountainous rise in well-being” associated with The Affluent Society, a consequence of what economists have called “the Great Enrichment” enjoyed most prominently but not exclusively by the United States since the mid-18th century.

This mid-20th-century affluence led to a kind of social and moral agonizing over injustice and inequity and an existential need for liberation, which increasingly meant freedom from any kind of constraint, moral or otherwise. One of the great services of Morrow’s account is to place the insanity and instability of 2020 within a broader historical frame. The bitter fruits harvested today have grown from seeds planted decades and even centuries ago. Morrow presciently writes of the 1960s, the Vietnam era and the time of the sexual revolution, for instance: “I trace our current troubles to that time—the youth of the boomers who are now old.”

This was also the time of the fight for modern civil rights, too, and Morrow’s insights into the racial history of America are worth considering. Drawing on the models offered by W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington, respectively, Morrow writes that “Du Bois and Washington represent different calculations as to pride, defiance or deference, and self-suppression. There was a psychic price to be paid if an American black followed Booker Washington’s way, and who was to say at what moment that price became too steep?”

Morrow does not presume to answer this question, which hovers as a kind of existential challenge for every black American to answer. Du Bois’s exploration of the “double consciousness” of being both black and American serves as a powerful reminder of the legacy of race and racism in American history. In Du Bois’s words, “One ever feels his two-ness—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.” Morrow’s attempts to reckon with these themes in his professional and personal life recall this insight from Du Bois, and Du Bois’s attempts can be seen as a salient background for later 20th-century strivings over civil rights and American history, notably the debate between James Baldwin and William F. Buckley. Baldwin hinted at a kind of double consciousness in his claim: “I love America more than any other country in this world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.” Baldwin’s sentiment in some ways crystallizes the moment we are experiencing in today’s discussions and discord over race in America. Love and legitimate criticism must go together and be seen as partners rather than alternatives.

Personality and History

In dealing with the divergence between Du Bois and Booker T. Washington, Morrow observes that the latter’s project was to prioritize economic opportunity and gain over legal and cultural recognition of equality and dignity. There was a kind of dignity, perhaps the most substantive, to be gained from productive and generative work on its own terms. Washington’s critics, writes Morrow, “had their minds fixed on black Americans’ rights, and beyond that, on their dignity.” By contrast, Washington “sought to build them the fundamental thing they lacked: an economic role in the society. He calculated that rights and respect would follow the money.” Perhaps this was true for many of the immigrants who came to the United States from all over the world throughout its history. But one can hardly think of the fate of Black Wall Street in Tulsa, Oklahoma or the impacts of violence on black entrepreneurship and invention without concluding that the rule of law and equal legal protection are prerequisites not only for making money but keeping it—to say nothing of the complex question of dignity—especially in the face of a history of racial prejudice, disenfranchisement, and enslavement.

On its own, money certainly seems to require gratitude, to the original giver of all good gifts as well as to those who have made it possible to earn and enjoy its benefits.

The histories that Morrow traces are not merely national; they are personal and familial as well. A variety of personages figure prominently in his essay into the wilderness of money and slavery, including a trio of Henrys: James (the novelist), Luce (the media magnate), and Adams (the historian). Siblings like Henry James’ brother William (the philosopher) and the Browns—Moses (an abolitionist) and John (most decidedly not an abolitionist)—also make important appearances. Morrow is certainly right to emphasize the interplay between personal and collective history. Many of the great figures of American history have been formed or malformed by their upbringings. As Morrow observes, given America’s equation of wealth with success, “The lack of money produces, especially in a child, an unbearable sense of unworthiness… and out of the injustice of that humiliation, a feeling of resentment that may become a permanent aspect of his character.” The social philosopher Michael Novak once keenly remarked, “Parents brought up under poverty do not know how to bring up children under affluence.” The intergenerational dynamics of wealth and poverty, especially as they relate to moral and spiritual formation beyond material prosperity, are a significant driver of contemporary American discontent. The Hebrew scriptures rightly reiterate the importance of inculcating virtue and remembrance of the past for each new generation. Those who grow up poor and experience some later prospering can in some measure appreciate the difference and be thankful. Those who grow up in affluence tend to view such blessings as a given, the baseline. Today’s privileges become tomorrow’s rights, while gratitude and responsibility are left behind.

To return to another of Mather’s images, if the mother of religiosity breeds prosperity, which in turn begets idolatry, unbelief, and irreligiousness, the American history of blessings and judgments hints at the only way forward toward true flourishing. “Give me neither poverty nor riches,” we read in Proverbs, “but give me only my daily bread.” Jesus taught his disciples to pray that latter request in his Sermon on the Mount, where we also find the truth as Luke writes that “blessed are the poor,” to which Matthew adds: “in spirit” (5:3). Another kind of “double consciousness” is necessary, it seems, for the proper valuation of money. Americans must see themselves not only as citizens of an earthly kingdom and having a temporal citizenship, but also as having an eternal destiny. For Christians, this comes to expression in an identity conscious of loves for and loyalties to both the earthly city and the city of God.

“Is money a miracle or a disaster?” wonders Morrow. Is it something to be thankful for or something to be mourned? It depends. Is money the god you serve or is your money in service to God? This dichotomy sets the parameters for the options facing Americans yesterday, today, and tomorrow, or what the Didache describes as the paths leading either to death or to life. On its own, money certainly seems to require gratitude, to the original giver of all good gifts as well as to those who have made it possible to earn and enjoy its benefits. If money so often leads to despair and ingratitude, however, we have to wonder if the problem is to be found ultimately in money itself or rather in those who love it wrongly. Whether money is ultimately a miracle or a disaster depends entirely upon what people “seek first” (Matt 6:33).