Progressives will never understand violent incidents until they look to human nature itself.

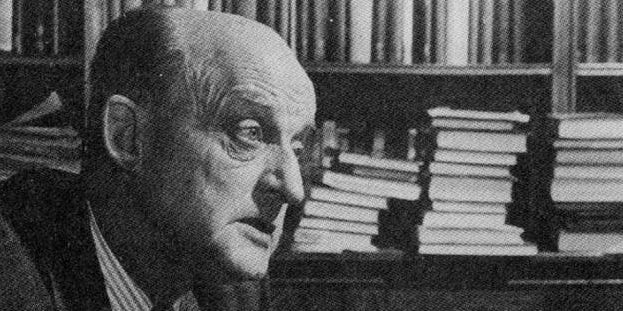

A Shrewd Diagnostician

A veritable fixture in the mid-twentieth-century American mind, Reinhold Niebuhr faded from view as the 1960s drew to a close. On the consuming issues of the day—civil rights and the Vietnam War—his convictions aligned with those of a vast swath of his fellow American citizens. What changed, what seemed to make him increasingly irrelevant, was the fading appeal of the framework of Christian realism that in the preceding decades Niebuhr had brought to bear on the issues of the day. The Great Depression in America; the ghastly Utopian schemes of National Socialism, Fascism, and Communism abroad; the carnage of World War II—did these not confirm that an impenetrable darkness resides in the recesses of man’s heart? A truly realistic assessment of man would surely rule out any dreamy illusion of innocence and natural goodness of the sort Rousseau gave us. In making such an assessment, Reinhold Niebuhr: Major Works on Religion and Politics, collected by Elisabeth Sifton, will be a valuable asset.

Niebuhr spent much of his writing life reminding latter-day heirs of the Reformation of their central insight, namely, that man’s sin is original, that it distorts all that man thinks and does. Man prides himself on being a child of light, who lords over all of creation, and deludes himself about the darkness within. In the Epistles of St. Paul, the gravity of the problem of original sin had first become a subject of sustained theological reflection. In Athanasius’ On the Incarnation, the co-relation of original sin and Incarnate God/man was clarified. In Augustine, a framework for thinking about history in light of sin and the Incarnation had been developed. During and after the Reformation, Luther, Calvin, and Kierkegaard, had further worked out its implications.

Now, during the most barbarous century in recorded human history, heirs of the Reformation were abandoning their fundamental insight about original sin and the catastrophe of human history that events around them most readily confirmed. In the tumultuous decade of the 1960s, the last wisp of this insight dissipated. America chose to forget, to ignore, to rebel; America chose the City of Man over the City of God. Niebuhr saw it coming. When it arrived, Niebuhr’s Christian account of this perennial temptation lost its purchase on the American imagination. No sympathetic effort to retrieve him for the last half-century—and there have been many—has prompted Americans to return to his fundamental insight. At the height of his influence, in the 1940s and 1950s, Niebuhr lectured to packed houses across the country; he was on the cover of Time Magazine; the great Hans Morgenthau, the father of the realist school of international relations, declared, “Reiny is my Rabbi.” College students were routinely assigned his books; for the reading public, his was a household name. Today, he is all but forgotten.

What accounts for this reversal? Why, after eleven centuries of Christian history in which the enormity of original sin remained unrealized in the bosom of the Roman Catholic Church—that is what Niebuhr believed—did original sin become, in the mid-twentieth century, an anachronism and an embarrassment for heirs of the Protestant Reformation?

One answer, the ahistorical answer, had already been laid out by St. Augustine in City of God. To be man is to rebel against God, to wish to forget Him. A rebel finds no satisfaction with the City of God, a City prepared for man before the creation of the world. Instead, the rebel/man conspires within himself and with others to construct a City of Man. Refusing his place in creation, which is to supplement God, by cooperating with His unfolding providential plan, the rebel/man insists instead on being a substitute for God. The Roman Catholic Church is not to blame. The problem precedes its emergence in the fourth century. Man himself is at fault. Adam and Eve’s first utterances were rebellious denials of their defection from God (Gen. 3:10–13). All subsequent generations have reproduced their rebellion.

The second answer, the historical answer, is that this rebellion has taken a particular form in modernity. Modernity is the succession of Christian heresies and apostasies in which a single key is said to unlock the riddle of suffering and open the door to man’s self-deliverance—capitalism, scientism, communism, psychotherapy, cosmopolitan liberalism, feminism, sexual liberation, environmentalism, and, now, identity politics. Niebuhr was at his best when critiquing these city-of-man schemes that offer faux redemptive histories. By the time the last four of these emerged into the light of day, Niebuhr had put down his pen; but in the two decades before and after World War II, he took on all the others, extracting the small part of what was true in them while showing that rest was delusion and detour. Look no further than Part V of The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness, reproduced on pp. 439–58 in this important volume, for Niebuhr’s prescience on the folly of neo-liberal cosmopolitanism today.

Niebuhr’s great gift was his ability to position the horrors of the twentieth century within the biblical horizon of Adam’s fall, Christ’s Incarnation, and the long patient wait for God’s providential plan of history to unfold. This is not the theology of Aquinas, in which reason’s light shines brightly, but rather of the late Augustine, who lives by faith and not by sight in the aftermath of the collapse of the Roman world. Only staunch Biblicists and, in a deeply twisted way, New Elect parishioners in the Establishment Church of Identity Politics practice this sort of thinking in America today. The former, Niebuhr rejected because they had disengaged with the world; the latter he would indict because they seek to transform the world, authorized by what can only be described as a Christian heresy. For Niebuhr, all of mankind is stained by sin, and as a consequence, all mortal institutions, including the churches, are tainted by that stain. The great longing in man for justice in a broken world remains unfulfilled, until Christ returns—not in love, but in judgment.

Identity politics declares that some are stained—the irredeemables—and some are innocent victims; and that the purity of the community, the code for which is “our democracy,” can be vouchsafed by purging—canceling—stain, be it “whiteness” or “dirty” fossil fuels. For Niebuhr, this would be yet another utopian scheme to cleanse the world. He himself witnessed a half-century of failed attempts to do just that, at the cost of one hundred million lives. Are we on the verge of another such cleaning, he would wonder? The darkness in man is not illuminated through a program of spiritual eugenics that separates pure and impure “identity groups,” as identity politics propounds. The darkness in man resides in every heart, no matter what the person’s race, sex (we must now refuse the term “gender,” which is a utopian illusion that sex is not real), ethnicity, or religion.

Niebuhr’s project, like that of post-modern thought today, involved a thorough-going critique of modern pretensions. But today’s post-modern thinkers are, in a way, the mirror opposites of Niebuhr.

Where should Niebuhr be located politically? He called himself a Christian Realist, and it is no secret that he was a lifelong Democrat. If his principal concerns could be consolidated, they would gather around three issues: the fragility of the middle class (hence his work with labor unions), a robust but non-expansionist foreign policy (he was continually worried about American hubris abroad, as the book makes clear in the essay, “The Irony of American History”) and, especially later in life, race relations in America. Neither major political party in America today gathers these three issues together, to their detriment. The middle class has been betrayed by both parties for some time, not least by trade policies that outsourced manufacturing jobs and immigration policies that drove down wages. Unionized labor had its malignancies; has the alternative been worse? While Democratic Party rhetoric focuses on innocent victimhood, its recipe for redress involves ever more government programs that provide a safety net but not a ladder to climb into the middle class. A faction of the Republican Party now claims to be a friend of the middle class; but it is hard to see how tax cuts, the perennial rallying cry, clear away the obstacles that now beset the middle class. On these two matters—the cause of the middle class and of a modest yet sober foreign policy—Niebuhr would today be politically homeless.

The contemporary reader of Niebuhr is disadvantaged not only because the doctrine of original sin seems to him strange, but also because the breadth of knowledge of the history of Western thought that Niebuhr evinced is likely to intimidate almost everyone who seeks a serious engagement with him. Niebuhr was a confident Christian, who believed that every intellectual movement within modernity could only fully be evaluated and understood in the light of Christianity. Try though it may, modernity could never take the measure of Christianity; it was rather the other way around: Christianity alone could take the measure of modernity. Far from shying away from modern thought, Niebuhr engaged it head on.

Niebuhr’s project, like that of post-modern thought today, involved a thorough critique of modern pretensions. But today’s post-modern thinkers are, in a way, the mirror opposites of Niebuhr. He sought to show that modernity’s highest aspiration—to establish a philosophical foundation for democracy, and for the idea of the person—was, finally, incoherent without Christian underpinning. The post-modern project rejects modernity on the ground that it has surreptitiously imported Christian categories—and with them older prejudices and mistakes that must be expunged. Nietzsche saw this clearly: “It is the church and not its poison that offends us,” he wrote. The post-modern project seeks to purge all the vestiges of Christianity. Niebuhr saw the failure of modernity and looked backward to Christianity for an antidote; post-modern thought looks backward at the failure of modernity and sees Christianity not as the antidote, but as the poison that made modernity toxic in the first place.

In times such as these, in which identity politics generates immense cathartic rage about race, though little productive action, it is worth saying a word about Niebuhr’s views on race in America, reproduced on pp. 651–54 of this important volume. In the world that identity politics invents, “racism” is the ghastly exception, something innocent victims are never guilty of. This group is the ghastly exception; the rest of innocent humanity is pure. Ever mindful that sin is universal, Niebuhr began with the fact—not the hypothesis—that individuals and groups are self-referential. Less generously, every group is naturally prejudicial towards every other group. Overcoming that problem requires more than DEI training can provide. The darkness of prejudice is so deep that only Christian forgiveness, atonement, and repentance can redress it. The darkness in man cannot be overcome by any project that man devises; man’s illness requires a Divine Cure.

In the twentieth century, communists sought to cure the darkness in the heart of bourgeois man through reeducation camps, purges, and exterminations. In the early decades of the twenty-first century, DEI commissars promise to cure “white privilege,” “unconscious bias,” “micro-aggressions,” and “systemic racism” through less malevolent means. But the century is young, and we will have to wait to see just how monstrous identity politics becomes before we form our final judgment. Niebuhr’s wisdom—Christian wisdom—is that man’s darkness can be lifted, but that no mortal plan can accomplish this feat. And yet the rebel/man refuses to stop trying to go it alone, to purify the world in which he is the most impure instance. Identity politics, the illness or our age, is the latest confirmation of this rebellion.

This collection of Niebuhr’s most important works should interest anyone who wishes to see an America in which, as recently as six decades ago, Christian thinkers did not confine their Christianity to the private sphere. The rapid collapse of Christian confidence, most emblematic in Rawls, who lost his faith after WWII, and who declared in A Theory of Justice (1971) that “public reason” must supervene over private religious conscience, is something from which we have not recovered. Niebuhr, the Protestant, and the inestimable Fulton Sheen, the Roman Catholic, who also occupied the American mind at mid-century, would have shuddered at this development. A society that pretends it can proceed without its religion is like the prodigal son who uses up his inheritance. For a time, it seems like he need not go home. But impoverishment does finally set in; and when it does, the prodigal son must decide whether he should sit there eating husks of pig corn (Luke 15:16) or return to the feast that awaits him in his father’s house.

It is not a stretch to see in identity politics this stark scene of feasting on the husks of pig corn, grasping for nutrition yet barely finding it. Identity politics, which is the religious pandemic of our time, will not be vanquished in the realm of politics, by a candidate who puts an end to government programs that further underwrite it. The disease is pre-political, and will need the pre-political antidote of Christianity, to properly recover. In hindsight, the virtue of Niebuhr, which many of the fine essays in this latest compendium of his works demonstrate, is that he saw clearly the catastrophe that was about to befall America. As a diagnostician, he is to be read carefully; as a doctor, who offered a cure, he fell short—leaving the churches today with the awful burden and responsibility of awakening to their deepest insights about the mystery of sin and atonement, which today they barely grasp.