Conservatives should not resort to the false promise of centralized political decision-making to fulfill their hopes of social recovery.

A Wokeness for Rad Trads

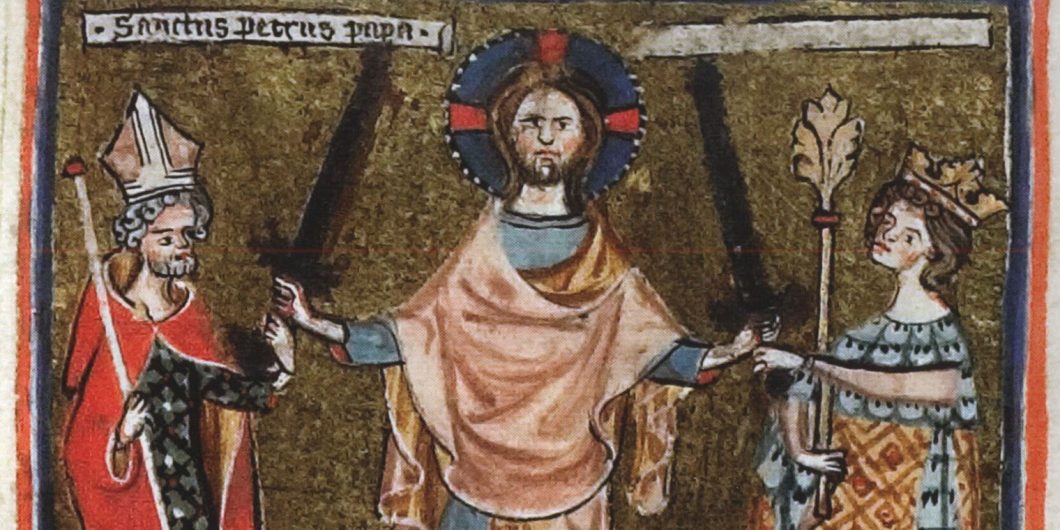

How times change. Ten years ago, at a meeting of conservative scholars, I saw a nationally known commentator lose patience with a younger panel member’s paper. The panelist was talking about a seemingly arcane point in early modern political theory: Does the pope have a potestas indirecta? Does the papacy have the political right to coercively remove a hostile but legitimate prince and to find a replacement ready to run the state in light of the Catholic faith? The senior conference-goer interrupted, saying all this talk of a papal deposing power had zero relevance to contemporary political thinking. A decade on, with the widespread collapse of confidence in liberalism amongst notable Catholic intellectuals, topics like the indirect power are back in vogue. Such ideas go by the name “integralism” and they have all the energy today. I recently polled some colleagues for the five contemporary Catholic theorists most important to read, and lists came back made up of integralists.

The best known integralists today are University of London philosopher Thomas Pink, Harvard law professor Adrian Vermeule, and the Cistercian Edmund Waldstein, who lives in an abbey in Austria, is a member of the editorial board of The European Conservative, and manages a website on integralism.

Integralism: A Manual of Political Philosophy is not a profile of these movers and shakers but a closely argued and ranging treatment of the integralist position. Penned by two Englishmen, Dominican friar Thomas Crean and theologian Alan Fimister, the book is substantive, the writing smooth, and the arguments forthright.

Union of Church and State

Integralism is the proposal that Christian peoples cannot be properly governed unless the state is completed politically by the Catholic Church. Integralists thus oppose the position of popes John Paul II, Benedict XVI, and Francis that the church addresses politics not by involvement in state power but by public persuasion. Inspired by Vatican Council II (1962-65), the contemporary papacy has situated itself as a shaper of conscience. Relying on human rights doctrine and granting the efficacy of the modern administrative state, the Church through speeches and opuscula has sought to shape the opinion of peoples and governments on issues of life, war, markets, inequality, and the environment.

Integralists think this approach naïve and confused. Naïve because fallen humanity cannot exercise virtue or obey natural law consistently drawing only on its own resources. The state is hobbled by failings in human nature and, perplexingly, the popes seem to have forgotten that we are also assailed by demonic powers. A true development of politics requires that grace inform the state. Grace—the word of God and the sacraments—must be made concrete in the state. This entails not only that the Church own property for services of worship, schools for teaching, and hospitals for tending the sick, but also that the state’s managers be baptized Catholics putting government administration to work for the highest good, human and divine.

To think of persons as parts of a whole—subjects of a state integrated with the Church—obscures that the Church’s natural law tradition has long held that human persons have a juridical completeness of their own.

Integralists also think recent papal social thinking confused. The popes have bolted human rights on to a new-fangled personalist philosophy, itself bolted on to Thomas Aquinas’s natural law. Integralist political theory does not take its origin from law, personalist phenomenology, or a state of nature postulate, but from the metaphysical claim that natures have ends to which actions must conform. The final end of human nature is supernatural and therefore politics is not complete unless integrated with the rule of the legitimate representative on earth of the supernatural, the Catholic Church under the leadership of the successor to St. Peter, the pope.

Hence, the opening page of Integralism: A Manual of Political Philosophy defines integralism as an “uncompromising adherence to the Social Kingship of Christ.” In addition, it is a political philosophy drawn from Neo-Scholasticism. A 19th-century retrieval of Thomas Aquinas, Neo-Scholasticism is a formalistic and highly rationalized version of the saint’s thought. Little use is made of recent popes, the authors preferring Leo XIII (d. 1903) and Pius XI (d.1939) as their writings made the greatest contributions to Neo-Scholasticism, sometimes referred to as the Manualist Tradition (hence the subtitle of the book). Rhetorically faithful to the manual style, the book begins abruptly with deductions from a metaphysical axiom rather than setting the scene for how intellectual history has brought some Catholic thinkers back to seemingly outmoded political arguments. This is something that makes the book valuable. Not only is the argument methodical and detailed, the footnotes are extensive and full of quotations from 19th- and 20th-century scholastic texts that few today know much about. Included are citations of Latin treatises written in the 1950s by cardinals debating whether, when popes invoke the deposing power, the correct legal term is declaration or deposition.

This history of Catholic ideas will be news even to most bookish Catholics. It is a scholastic tradition which university Catholicism left behind. Moving deductively from a premise about natures and their ends to an unspooling of the consequences contrasts markedly with the dialectical style of university Catholicism, which aims to sustain Catholicism by bouncing off secular thought. It is easy to forget that John Paul II and Benedict were professor-popes, popularizing 20th-century theologians like Erich Przywara, Henri de Lubac, Karl Rahner, and Hans Urs von Balthasar, who were in active conversation with secular intellectuals. It is the professor-popes who decisively turned Catholic social thought towards the contemporary university. Integralism: A Manual of Political Philosophy is a deep dive into a subterranean Catholicism, therefore, and even if you cannot agree with the argument, the book is a tremendous resource.

Devaluing the Human Person

“We have argued that `the State,’ conceived as a perfect society generated by man independently of divine revelation, is a false category,” the authors announce. Rather, they argue, societies are well-ordered when they enable “the part to be perfected by taking its proper place within the whole. The good of a part as such lies in being well ordered toward its whole; hence the good of a person who belongs to a society, insofar as he belongs to it, is to tend towards its common good.” Individual, state, and, Church are like so many nesting dolls. Organicism places each not only in a specific order but in a radical dependence on the overarching whole, the Church. This is because human persons have a supernatural end “which infinitely transcends the good of any natural society.” The Church does not merely cap things off, therefore, but is the whole—earthly and cosmic—from which the parts are derived. Society is not the coming together of discrete, autonomous parts for mutual projects, but more like a rose, a singular unity unfolding and relaxing into so many connected iterations.

In laying claim to an older ecclesial political philosophy, which they summarize as “the principle of subordination of part to whole,” Crean and Fimister elide the fullness of the Catholic legal tradition. To think of persons as parts of a whole—subjects of a state integrated with the Church—obscures that the Church’s natural law tradition has long held that human persons have a juridical completeness of their own. Natural law does not sponsor organicism.

In a letter to the Roman Emperor, Pope Gelasius (d. 496) stated that the world was governed by priestly and regal powers, the former being, said Gelasius, the “weightier” of the two. Unsurprisingly, the letter proved contentious. Even in the Middle Ages, opinions varied widely. Some theologians thought papal power absolute whilst others held that natural law gave the citizens of Rome permission to vote in the pope. Famed Spanish Thomistic jurist, Francisco de Vitoria (d. 1546), argued that the state is a perfect society. Under natural law, he argued, the state has a juridical standing underived from the Church, just as individuals have legal protections underived from the state. Crean and Fimister suggest that the individual has no such rights underived from the state, and that the state has no such standing underived from the Church.

De Vitoria argues that homicide is an offence against God, who is master of life and death, but also an offence against the individual killed, as each of us is a bearer of rights on account of our lordship (dominium) over self. According to Crean and Fimister, “an innocent man has the right to life because anyone who kills him is harming the common good, of which an innocent man is an important part.” A killer, however, is not transgressing a right to life stemming from “human nature without reference to any society.” Each chapter ends usefully with a list of formal propositions, a shorthand version of the chapter. One proposition runs: “The rights of rational creatures are not qualities intrinsic to them but derive from the extrinsic end of a society to which they belong.” Belief in intrinsic personal rights could only stem from an intuition, but “the human mind does not intuit the properties of things, but discovers them by observation and reasoning.” Are intuitions really uncompelling? De Vitoria has a nifty example to tease out whether we could be satisfied thinking that our individual legal standing is derived exclusively from our being a part of a common good (whether a state or a society exhibiting an integrated church and state).

The natural law tradition maintains that, though we are spiritually damaged, we retain enough integrity to know and obey the law. Our wounded nature still has resources enough to muddle through.

A city is under siege and the besiegers offer a deal. Rather than raze the city to the ground, the attackers will leave the city alone if the city picks one innocent resident and kills him (her, or child). The common good appears to require the city indeed pick someone and dispatch that innocent. De Vitoria argues this would be a tyrannical act, for no person is simply a part of a whole. Crean and Fimister seem to think that persons relate to the state as members do to a body. Rejecting this organicism, de Vitoria: “For a member cannot suffer injury, since it does not have its own proper good to which it has a right. But a man can suffer an injury, since a man has a proper good to which he has a right. . . But an innocent person is his very own good and alone he suffers, and therefore it is not lawful to kill him.” This is an intuition worth holding on to. The example shows that persons are wholes with juridical standing underived from claims of the city (terrestrial or divine). De Vitoria uses this reasoning to condemn political rites of human sacrifice.

It is not just the mereology—the analysis of parts and wholes—that runs counter to critical moral insights from personalism and natural law, but also the authors’ metaphysics of perfection. Crean and Fimister:

Without the spiritual power, men have not the moral resources to attain to the elements of their natural good which they discern by reason. Fallen man cannot exercise natural virtue consistently, or keep the commands of natural law entirely, by the power of nature alone. To do these things, he must be justified, that is, endowed with sanctifying grace, which comes from the preaching of the word of God and the sacraments of the Church. (emphasis added)

The natural law tradition maintains that, though we are spiritually damaged, we retain enough integrity to know and obey the law. Our wounded nature still has resources enough. We will not consistently and entirely live to the highest possible moral standards, but we will muddle along pretty well. Amidst legion moral failings the world over, children mostly show piety to parents, professional armies usually do not commit atrocities despite intense violence, business interactions are generally honest, and young people still help the elderly struggling to cross the street. And yes, interactions with the police are typically by the book.

Societies function because most people are reasonable and have a keen sense of fairness. Adam Smith astutely observes that justice is keyed to play: “In the race for wealth, and honours, and preferments, he may run as hard as he can, and strain every nerve and every muscle, in order to outstrip all his competitors. But if he should justle, or throw down any of them, the indulgence of the spectators is entirely at an end. It is a violation of fair play, which they cannot admit of.” Our authors seem to conflate sin with being unlawful, but fair play and rule of law are not tied to a standard of perfection.

If a conflation is afoot, the implications are significant. Here our authors sketch out the deposing power:

For this reason, we say that the vicar of Christ has a direct spiritual and temporal jurisdiction over Christendom, although he can only exercise the latter on rare occasions. . . . Within Christendom, the body that moves to free itself from a tyrant extra-judicially must seek the confirmation of its action, after the fact if necessary, from the sovereign pontiff; and he may also take the initiative in declaring the tyrant’s loss of authority.

In the parlance, this passage shows the authors think the papacy has a direct, and not merely indirect, power in the state. This radical position is consistent because they do not imagine church and state like a double-decker but as blended, albeit with the state having some relatively autonomous competencies. However, the critical point is that the mereology and perfectionist metaphysics is an invitation to a radicalism that sits uneasily with rule of law. The power of Integralism: A Manual of Political Philosophy is that it forces readers to ponder what Christians, and especially Catholics, should hope for politically. If you want to know what integralism means concretely for our political lives, this book is full of proposals engagingly explained inside an elaborate theoretical framework. These arguments have the wind in their sails. It is not just the Left who are woke: a spirit of radicalism is abroad inside much of the Catholic intelligentsia, too.