Neo-integralists today lack formation in republican institutions, and succumb too easily to the lure of authoritarianism.

An Unserious Catholic Politics

In recent years, an odd phenomenon has occurred in American conservatism. Well, perhaps there has been more than one. Yet the most surprising has been the ascendancy of Catholic integralism. Rejecting liberal political theory, integralists have argued that separation of state and Church is a dead-end road and that Catholics need to return to a political vision in which the City of God and the earthly city cooperate closely; indeed, that the state is the secular arm of the Church and ought to assist in the salvation of souls. It is truly surprising that this vision has gained traction in the United States of all places. Nevertheless, it has become increasingly popular among young Catholics, who are tired of liberal conservatives and desire a re-sacralized public square.

The general response by conservatives to integralism has been disdain and rejection. According to fusionists, classical liberals—and even national conservatives—integralists are, at best, utopian idealists and, at worst, fascists. Integralists for their part have been quite willing to attack conservatives, who they present, at best, as naive would-be reformers of a defective liberal order, and, at worst, as heretics who ought, in a proper integralist regime, to be chided for their views (to put it mildly).

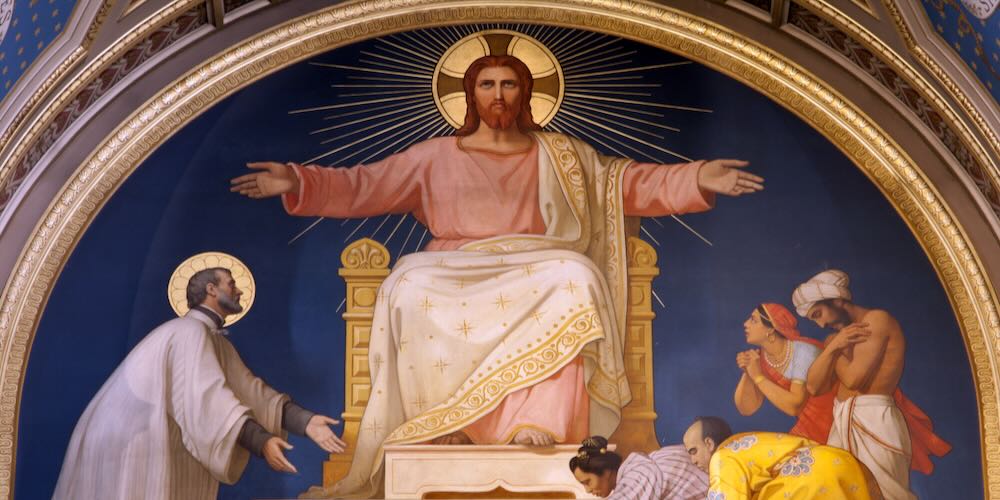

It often seems that the two sides are talking past each other, and in the often-heated debates, they may forget a more important truth: that as Christians, they are all brothers and sisters in Christ and mere pilgrims on earth on the way (God willing) to Heaven, where they will spend eternity praising God together in mutual love, even if they blocked each other on Twitter in this wretched world.

In All the Kingdoms of the World: On Radical Religious Alternatives to Liberalism, Kevin Vallier goes a different route. A liberal and Eastern Orthodox, Vallier sets himself a worthy goal that he fulfills for the most part: to truly understand integralism, to take it seriously, and to critique it thus in a more convincing way.

Vallier looks at integralism in five areas to determine its veracity and viability. He considers the first two to be strong points of integralist theory, while the latter three are presented as the main problems in realizing it:

- The Historical Argument: Is integralism in line with Church history and doctrine?

- The Symmetry Argument: Is the integralist vision of Church and state as two orders, with the former being superior to the latter yet both aimed at the supernatural life, logical?

- The Transition Argument: Is it realistic that the current liberal regime could transition to an integralist regime?

- The Stability Argument: Would an integralist regime in today’s world be stable without descending into tyranny?

- The Justice Argument: Would an integralist regime be just?

The strongest part of the book is the chapter on the symmetry argument. Vallier masterfully shows the immediate appeal of integralism that liberals have so far been unable to reply to sufficiently: if our heavenly destination is superior in importance to our earthly life, then why should not the spiritual authority that helps us toward our salvation (the Church) be superior to the authority dedicated to earthly goods (the state)? Why should the state not be in service of the Church? Or, we might take one step back and ask more generally: Why should a political society completely disregard Heaven when it is actually what matters the most? Do we not need God’s grace, especially through the supernatural goods of the sacraments, to make politics more than just a sinful battle for power, to be able to work toward a truly virtuous political order? Vallier makes clear that integralists have a strong point here, and he convincingly critiques those schools of thought that only focus on the “basic goods” of human life while disregarding the supernatural ones.

According to Vallier, integralists can fulfill their dreams if they try to implement theocracies on the local level, in which they “support an explanatory order of micro-polities” within the liberal order.

Equally convincing is Vallier’s critique of Adrian Vemeule’s notion of “integration from within.” Vermeule famously argues that liberalism will die soon, so integralists can strategically position themselves within the political system to take over when everything falls apart. Or, in Vallier’s summary of this integralist hope, “perhaps a new Catholic Christendom can arise from the ashes of doomed American liberalism.” In great detail, Vallier shows that this is fanciful thinking—indeed, that transitioning to integralism, especially in our modern, globalized, and pluralistic world, is a sheer impossibility and, if tried, “requires grave sin.” He also makes some excellent, novel points, for instance, looking at state capacity theory. State capacity has increased dramatically in the last centuries, but integralism requires a low state capacity so that states have to listen to the spiritual authority. Further, Vallier introduces Hayek’s knowledge problem, showing how integralists, in our complex world, will be just as inept as socialists at knowing the tacit knowledge on the ground.

Less convincing are the chapters on the historical and stability arguments. In the first case, Vallier presents a Catholic political history that ends up vindicating the integralists. Indeed, he argues, “authoritative figures, church documents, and institutional practice [in Catholicism] support” integralism. Overall, it is a strong analysis, but it also lacks details and becomes oversimplified and unnecessarily one-sided. Christian thinkers were not all in agreement about political questions prior to the modern age, but Vallier cherry-picks certain aspects of history and doctrine for the integralists, such as oversimplifying advocacies for integralist policies (for example, in St. Augustine) or taking council statements out of context. He attempts to show that when it comes to history and the magisterium of the Church, there are no easy answers. That may be true, but sometimes he strangely makes it too easy for his opponents. Eventually, he simply gives up on a satisfactory solution as he ends the chapter by calling dogmatic debates “bewildering” and the historical debate “too difficult.”

In the chapter on the stability argument, Vallier explains that integralist regimes would never remain stable in our pluralistic systems. Sooner or later, they would either become tyrannical or be destroyed by the pluralistic elements in society. While the main thrust of the argument seems accurate, his explanations could rub integralists (and Catholics overall) the wrong way. Two points in particular need to be addressed: First, Vallier constantly compares and implicitly equates integralism with Italian fascism, communism, and modern-day China. He argues that an integralist regime would use a mass surveillance system, a Chinese social credit system, and engage in manifold human rights violations. Certainly more recent historical examples of integralist states should caution us of embracing this alleged ideal.

Yet, Vallier never offers any citations of today’s integralists actually making arguments along those lines or advocating for fascism. Instead, he regularly accuses integralists of “creating paywalled publications” and “selling tickets for conferences they headline” (nobody else seemingly does it). Considering that one of Vallier’s chief goals is to move away from a knee-jerk tendency to rubber-stamp integralists as totalitarians, these comparisons are unfortunate and inadequately supported by evidence.

Second, in one of the book’s oddest segments, Vallier builds a model—yes, a model with graphs!—in which he pits grace against pluralism. According to integralist thought, politics can be saved from the sinfulness and depravity of the world if a regime is ordered toward the supernatural, since grace can then flow and transform the political society. Vallier’s conclusion of his odd modeling in which he “estimates grace” (something he simultaneously admits is far-fetched) is that an integralist regime would never have enough grace to be stable. Yet, we must, it almost seems needless to say if it wasn’t for this chapter, question the idea of “estimating grace.” Surely, an integralist could simply answer (and convincingly so) that grace cannot be modeled but is overflowing if we have faith. After all, faith can move mountains, and with enough faith, “nothing is impossible for God,” not even integralist regimes. Thus, while Vallier’s general point that integralist regimes are unlikely to be stable and durable in the modern world is a strong one, the approach he takes is unnecessarily obscure.

Perhaps the most problematic part of the book comes at the very end. Considering integralism of the Vermeulian type as defeated, Vallier introduces “a new integralist strategy that can satisfy postliberals and even fit within a liberal framework.” He names this alternative “integration writ small” and it is a combination of liberalism and the Benedict Option. According to Vallier, integralists can fulfill their dreams if they try to implement theocracies on the local level, in which they “support an explanatory order of micro-polities” within the liberal order. The suggestion that it is possible to have integralism within a liberal polity is surprising—after all, Vallier has abstained from looking at liberalism throughout the book. But precisely because he has not engaged with postliberal critiques of liberalism, his conclusion has to sound like wishful thinking to postliberals.

Thus, at the very end of the book, it is suddenly Vallier who sounds utopian: left-wingers should accept religious, illiberal communities on the ground. Right-wingers should accept LGBTQ communities. And libertarians should accept welfare statism. Then, when we have all accepted that everyone should “downplay their differences,” we will get along. The greatest “diversity in racial, sexual, and gender characteristics and in religious and political worldviews” would be achieved and ought to be “treasured” by the government. And these liberal governments should protect diversity by helping these small, illiberal communities survive. In the case of integralists, “liberal governments may have to insulate these communities from drugs and pornography, and they may even have to protect them from the egalitarian culture of liberal elites.” Or, the liberal elites ought to protect integralists from the liberal elites.

What consequences does our Heavenly Citizenship in the City of God have here on earth? Or does it simply have no consequences?

What is the point of this beautiful world where everyone gets along by ignoring each other in their isolated mini-states, with a liberal hegemony ruling over them? It is “to pursue the ever-present possibility of peace.” And yet, as the integralists might say, this earthly peace is incomparably inferior, and indeed illusional, in contrast to that Heavenly Peace that St. Augustine pronounced to be our goal and destination, our way of life in building an order of love and mercy. Is Christianity not more than just a custom of building small communes in monastic discipline, locked in and protected from the outside world (as important as these monastic communities are)? Does the Church not properly invest its energies in evangelizing people, bringing the love and truth of Christ into the larger society, even if it is hostile?

The attempt to present a positive alternative is a good idea in and of itself. Otherwise, integralists could still argue that even if integralism is admittedly imperfect, it could still be “the worst form of government, except for all the others”—especially except for liberalism. It would have been fruitful, however, to consider new, perhaps even non-liberal, ways of defending free political regimes and religious liberty. To name just a few, Vallier could have looked at an Augustinian-Ratzingerian vision of two cities that adopts the “two-polity political theory” in which the Church—the perfect political society—and the state are separate, important entities with an overall symmetry but distinct purposes; at the European tradition of Christian democracy; or at a Newmanian vision of personhood and Church conscience that requires individual freedom and independence of government intrusion. These alternatives go beyond the scope of this review, but they could have been more intriguing for both integralists and many other Catholics than theocratic “charter cities” that are at the mercy of the modern state.

This is not meant to dissuade the reader from engaging with All the Kingdoms of this World; rather, these few pushbacks are meant in the same spirit of friendliness and respect that Vallier displays towards others. The general point remains the same: Vallier has done conservatives and Catholics in particular a great service in writing this thought-provoking book. For anyone with an open mind, this will be a book to grapple with, since everyone will find interesting and unexpected arguments in it that will challenge their own opinions. It is to be hoped that this book can be the starting point for much more: as Vallier proves, in taking integralism seriously, even non-integralist Catholics can benefit a great deal from its ascendancy. Though some vocal integralist voices have made abstruse and dystopian claims on a regular basis, the system of thought still poses a great challenge to the secularized society of our day in which religion has been relegated to the private sphere, if it even still exists there. Why should politics be fully detached from the Heavenly if we are called to sanctify the world, including the society we live in? Why should religion be a mere “basic good” in politics, coequal with all other earthly concerns, when Jesus seeks us out in the Sacraments to sanctify, renew, and purify us and where He draws all of us together “politically,” as Catholics believe? What consequences does our Heavenly Citizenship in the City of God have here on earth? Or does it simply have no consequences?

Integralists challenge us to answer these questions anew—and perhaps, to find better and more convincing ways for Catholicism and freedom to be reconciled. Perhaps even together with them, we can take up that much-neglected task that St. John Henry Newman laid at the feet of all Catholics in the nineteenth century: the task of “uniting what is free in the new structure of society with what is authoritative in the old.”