Building a Rights Tradition in the New Nation

If there is one portion of the U.S. Constitution the typical American is at least superficially acquainted with and even makes occasional appeals to, it is the Bill of Rights. It is almost certainly the most celebrated feature of the national charter, often spoken of in reverential tones. This is not without irony given that the Bill of Rights was not framed by the Constitutional Convention. Indeed, George Mason’s September 12, 1787 motion at the Philadelphia convention to “prepare a Bill of Rights” was unanimously rejected by the state delegations voting on it. Rather, the initial amendments to the Constitution, now known collectively as the Bill of Rights, were hastily deliberated by the first federal Congress and tacked on to the end of the ratified Constitution to assuage its critics and silence calls for sweeping revisions.

Who needs a bill of rights, and what does one look like? What did Americans of the founding era mean by “rights,” and what was their conception of a declaration or bill of rights? What is a bill of rights’ standing in law, especially in relation to a jurisdiction’s constitution and other expressions of fundamental law? Who or what authorizes, frames, and legitimizes a bill of rights? These questions were apparently on the minds of Americans in the newly independent states in the wake of independence and the years leading up to the framing and ratification of a national constitution.

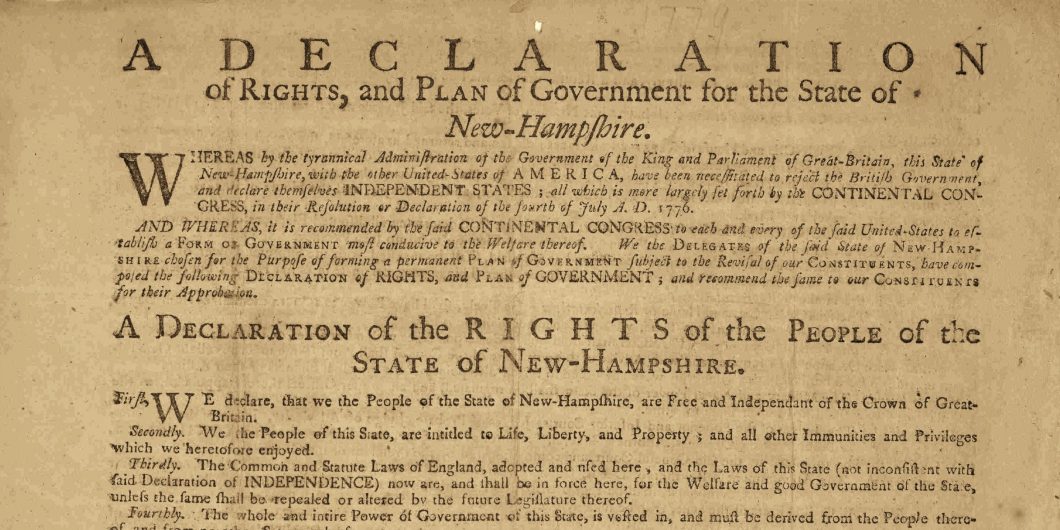

Early State Expressions of Rights

These are also among the questions considered by Peter J. Galie, Christopher Bopst, and Bethany Kirschner in Bills of Rights Before the Bill of Rights: Early State Constitutions and the American Tradition of Rights, 1776-1790. Their study is a comprehensive, systematic documentary history and analysis of the character and content of the early declarations of rights and an emerging “rights tradition” in the former colonies and Vermont in the 15 years or so following independence. Their interest in these documents and other expressions of rights in the new republics is not merely as “dress rehearsals for the national Bill of Rights” framed by the first federal Congress in 1789 and ratified by the states in 1791; rather, they examine these declarations on their own terms as developments in the new nation’s heritage of rights. They consider what these declarations communicated to the societies for which they were framed and how they functioned in these polities.

Did these declarations, the authors ask, reflect common themes and reveal a coherent moral and political philosophy? Several characteristics, they argue, demonstrate a coherence in these declarations: the articulation of specific constitutional principles upon which the political community was founded and which were essential for a new republican order to succeed; the expression of fundamental rights upon which other liberties depended; and the affirmation of rights rooted in the English constitutional tradition that the former colonists believed had been infringed by Crown and Parliament. Among the rights frequently mentioned in these declarations were the freedom of the press, trial by jury, the sacred rights of conscience, due process of law, the right to petition the government for redress of grievances, freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures, and a cluster of rights available to the criminally accused, including the right to be informed of criminal charges, to confront accusers, and against self-incrimination.

An introductory chapter provides an overview of the study of rights and declarations of rights in the founding era. This is followed by two illuminating chapters that discuss the sources of rights in the colonies and give a brief survey and comparative assessment of the emerging rights traditions in the first constitutions of the former colonies and Vermont. These chapters are prologue to fourteen chapters examining the expressions and protection of rights in each state following independence, looking first at the eight states that prefaced their constitution with a declaration of rights, then the four states that lacked stand-alone declarations, and finally the two states that retained their colonial charters as their state constitutions.

Each chapter profiling a specific state begins with a summary of the history and content of colonial expressions of rights and fundamental and statutory laws regarding rights protection prior to independence, devoting special attention to the institutions and processes of self-government, religious liberty and church-state arrangements, and political developments leading to independence. This is followed by an examination of constitutional developments after independence (including, in most states, the framing of a declaration of rights). These sections are especially attentive to the scope of suffrage rights, structural restraints imposed on civil government and its officers, methods for revision of fundamental law, and reception of common law. Relevant portions of key documents are then reproduced with notes and commentary reflecting a close reading of the documents. These notes, inter alia, comment on continuity with and departure from English and colonial antecedents, identify unique features and innovations, and trace sources of influence on specific provisions (including the influence of other state declarations). These valuable annotations document the lineage of ideas and emerging themes in constitutional thought.

As many as seven states framed their declarations with a copy of the Virginia Declaration of Rights in hand, along with scissors and pastepot.

The documentary evidence marshaled in this sourcebook indicates that in 17th- and 18th-century America, leading up to the separation from Great Britain, the words “rights” and “liberties” encompassed an expansive range of meanings. And, as Americans reconstituted their polities in the aftermath of independence, they debated the nature of rights—their sources, meanings, and scope.

Do Republics Need Bills of Rights?

In Federalist 84, Publius (Alexander Hamilton) answered those who criticized the proposed Constitution because it “contains no bill of rights” and countered calls for the addition of such a bill. He made nine or ten distinct arguments, with hints of others. One argument is that

Bills of rights are, in their origin, stipulations between kings and their subjects, abridgments of prerogative in favour of privilege, reservations of rights not surrendered to the prince. . . . It is evident, therefore, that according to their primitive signification, they have no application to constitutions professedly founded upon the power of the people, and executed by their immediate representatives and servants.

Other Federalists similarly argued that bills of rights are inapt (and unnecessary) in republics, where power is derived from the people, insofar as bills of rights only protect the people from themselves. This may be a clever argument, but it apparently found little currency in the eight newly independent republics that framed declarations of rights in the decade between 1776 and 1786. (Perhaps they would have been more convinced by the Federalists’ other arguments for why a bill of rights was more appropriate to check governments of general powers—like those of the states—than ones of expressed, delegated powers like the new national government.)

The history recounted in this volume also confirms that there was no consensus regarding who or what was authorized to frame and adopt a declaration of rights. Some declarations were crafted by special conventions, others were framed by revolutionary-era legislative assemblies. Most were approved by the body that drafted them, and a few were ratified by the people in conventions or town meetings. Some declarations were free standing in a state’s organic law, others were folded into the body of a state’s constitution, and, in some states, expressions of rights were sprinkled throughout a constitution or adopted by way of ordinary legislation. Declarations in a few states were written and adopted before attention was turned to framing a plan of government; in other states, they prefaced or were incorporated into a constitution; and in still other states, there was no declaration of rights at all.

Looking to Virginia for Examples

In Virginia, the first of the former colonies to adopt a declaration of rights (June 12, 1776), the sequence in which its declaration and constitution were framed seems deliberate. On May 15, 1776, the Fifth Virginia Convention passed a resolution instructing the Commonwealth’s delegates at the Continental Congress to press for a declaration of independence from Great Britain. This bold initiative raised questions about the nature of civil authority extant in the Commonwealth. Believing, perhaps, that they had reverted to a state of nature, the delegates thought it necessary to frame a new social compact, beginning with a declaration of humankind’s natural rights, followed by a new plan of civil government.

The Virginia declaration, largely the work of George Mason, proved to be among the most influential constitutional documents in American history. As many as seven states framed their declarations with a copy of the Virginia declaration in hand, along with scissors and pastepot. (Interestingly, a widely-circulated preliminary draft of the declaration, it turns out, proved more influential than the final draft.) With remarkable brevity and clarity, it distilled the great principles of political freedom inherited from the English constitutional tradition, including principles extracted from Magna Carta (1215), Petition of Right (1628), the English Bill of Rights (1689), and the long struggle to establish parliamentary supremacy culminating in the Glorious Revolution of 1688. It combined a commitment to fundamental liberties with a brief expression of constitutional principles and political ideas expounded by John Locke, Baron de Montesquieu, and other political philosophers.

These sources, along with colonial charters and codes, natural law/rights ideas, and theological traditions, informed the emerging rights tradition in the states. Each of these sources—none more so than the due process principles in articles 39 and 40 of Magna Carta (1215)—found expression in the state declarations.

A True Bill of Rights

While Americans in the 20th and 21st centuries have grown accustomed to thinking of a bill of rights as an enumeration of individual rights enjoyed by citizens, it was not always so. Bills of Rights Before the Bill of Rights reminds readers that, as evidenced in the English Bill of Rights and Virginia Declaration of Rights, a bill of rights could include both an enumeration of individual rights and, perhaps more important, structural features (such as separation of powers implemented in manifold ways) designed to restrain the powers of civil government that might otherwise tyrannize the people’s liberties. The Virginia declaration, for example, separated legislative and executive powers from judicial power; promoted term limits; required free, frequent, and regular elections; and discouraged standing armies in time of peace.

In the constitutional ratification debates, partisans on all sides argued that a true bill of rights was to be found in structural provisions that would restrain the powers of civil government. A bill of rights that enumerates individual rights absent structural restraints, they warned, may prove to be a mere parchment barrier. When leaders of the so-called Anti-federalists, like George Mason and Patrick Henry, complained that the proposed national Constitution lacked a bill of rights, they were arguing that the proposed government, with its consolidated powers, lacked real, meaningful structural checks on its powers. As Patrick Henry declared with rhetorical flourish in Virginia’s ratifying convention on June 5, 1788, “[t]here will be no checks, no real balances, in this government. What can avail your specious, imaginary balances, your rope-dancing, chain-rattling, ridiculous ideal checks and contrivances?” Thus, the Anti-federalists agitated for a bill of rights that focused as much, if not more, on structural restraints as on individual rights. This volume is appropriately attentive to both individual rights and structural restraints in early state constitutions and declarations of rights.

Bills of Rights Before the Bill of Rights dispels the notion that the early state declarations of rights should be read and studied merely as “dress rehearsals” for the national Bill of Rights. Aspects of the state and national bills of rights emerged from a rights tradition that drew deeply on English and colonial antecedents. The early state declarations, however, were, in important respects, different in kind from the national Bill of Rights insofar as they were crafted for different political communities, functioned in a different context, and were designed for different purposes. Yes, those Americans who subsequently debated, framed, and ratified the U.S. Bill of Rights drew on the articulation of rights in colonial documents and in early state declarations of rights; nonetheless, these state declarations merit scrutiny on their own terms as distinct and noteworthy contributions to the nation’s heritage of rights. Bills of Rights Before the Bill of Rights appropriately acknowledges and examines, with extraordinary attention to detail, the distinct contributions these early declarations made to a developing rights tradition in the newly independent states; and for this reason, it is recommended reading for students of constitutions, rights, and bills of rights.