NATO expansion will secure and promote peace inside and outside of Europe.

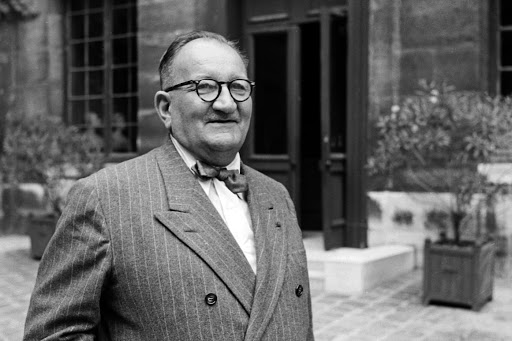

Étienne Gilson's City of God

Étienne Gilson (1884-1978) was a famous Catholic historian of medieval philosophy who enjoyed a long, productive, and laureled career during the first three-quarters of the twentieth century. He was also a philosopher in his own right, who, along with Jacques Maritain, Josef Pieper, and others, led a revival of interest in St. Thomas’s philosophical thought, including circles outside of the Catholic Church. These twentieth century giants shared the twin aims of comprehending Thomas’s authentic philosophy and of using it to engage with modern currents of thought, such as positivism and existentialism.

In the 1930s, Gilson engaged in an intra-Catholic debate over the legitimacy of a phrase he had employed: “Christian philosophy.” Certain thinkers objected to it, arguing that there is nothing specifically Christian about philosophy. The phrase was misleading and fed into the suspicions of those who suspected the infiltration of dogmatic tenets into purportedly philosophical or natural law propositions. Gilson responded that while he agreed that philosophy enjoyed a real autonomy as a discipline, with its own methods, criteria of evidence, and modes of argumentation, in the “concrete,” that is, in the life of the believing thinker and in the history of thought, Christian doctrines had played important roles in the development of philosophy. They had opened vistas for thought unsuspected by non-believing philosophers and had warned of shoals that needed to be avoided.

The debate indicated that Gilson’s understanding of what the historian of philosophical thought needed to come to terms with was rather complex. To the traditional neoscholastic categories of “reason” and “faith,” “nature” and “grace,” he added “history” as the site and laboratory of their interaction. Nor was this category of history of merely historical interest. Once convinced of their truth, a philosopher could take these historically occasioned concepts and deploy them in contemporary debates. Thomas’s metaphysics of existence, for example, could be brought into dialogue with its contemporary namesake, existentialism, while Christian personalism could help adjudicate between the dueling anthropologies of Marxism and liberalism.

The Metamorphoses of the City of God displays Gilson the historian and philosopher turning his attention to another set of contemporary issues, this time taking his bearing by Augustine’s great work, the City of God. The choice of Augustine was dictated by the topic and the times. The time was 1952, the place, the Catholic University of Louvain (in Belgium), where he gave “the inaugural [lecture] course of the Cardinal Mercier Chair,” which in turn became the book. The setting allowed for a self-consciously Catholic treatment of the topic. It also permitted a noticeably personal voice. The written version allowed its author to add some important notes.

What was the topic of the lectures? As their title suggests, it was a series of medieval and modern “metamorphoses,” or proposed earthly realizations, of the City of Peace laid out in Augustine’s masterpiece, but on different premises. In addition, Gilson framed this historical investigation with a sketch of the present. He wanted to be able to draw lessons from the past and apply them to the present. He therefore identified three dramatic challenges facing contemporary humanity: the challenges of universal history, the ideological divisions of the Cold War, and of European Christian Democracy. First of all, due to Europe—to European colonization, to its exporting of universal ideas and techniques, to its successive world wars—the human race had entered into a new phase of interconnectedness, what Raymond Aron later called “the dawn of universal history.”

Planetary unity has been achieved. Economic, industrial, and technical reasons in general, all of which we can view as tied to practical applications of the natural sciences, have established a de facto solidarity among the peoples of the earth. Consequently, their vicissitudes are combined in a universal history of which they are particular aspects. Whatever the different peoples of the world may think about it, they have become parts of a humanity that is more natural than social.

The last phrase, “more natural than social,” indicated a great task:

Henceforth, they must become aware of that humanity in order to will it instead of just undergoing it, and in order to think about it with a view to organizing it.

What is called for is a truly “universal human society,” “a universal society coextensive with our planet and capable of uniting the totality of humans.”

Here Augustine himself could help, as he was the first to articulate this striking “ideal.” He laid out its spiritual requirements in the City of God. He also provided canonical understandings of “society” (societas) and “people” (populus). The “universal society” would perforce have to be a genuine “society,” a union of minds and hearts centered around common objects of love, and it would have to be “a society of peoples.” Assuredly, these Augustinian stipulations raised thorny questions and Gilson was quite aware of them. We will return to them toward the end.

Current humanity, however, was riven by the division between two contending ideologies and blocs, between Marxism and liberalism, and between the Soviet Union and the free world of democracies. This division was particularly visible in Europe itself, divided by what Churchill called “the Iron Curtain.” Here too Augustine could help understand matters, this time with his concept of “the Earthly City.”

[T]he Civitas Terrena’s [ …] impact upon the temporal sphere is no less visible and no less powerful than that of the Heavenly City. That has never been clearer than it is today. Marxism is the most sustained effort the world has ever known to establish the perfect coincidence of the temporal city and the Earthly City. It actively prepares the reign of the Anti-Christ.

Given the radical nature of the Communist challenge, the response to it must be as well. This entailed a “hard saying” that neither protagonist, Marxist or liberal, was disposed to hear: the affirmation of the God-given authority of the Church over temporal affairs. Gilson took pains to explain that this does not mean the direct involvement of spiritual authority in temporal rule, but rather the safeguarding of politics and of man himself against their demonic degradation:

The Church’s jurisdiction over the temporal realm has precisely the goal of preventing him from putting it at the service of the Earthly City…

Even pagan Romans knew that human pride needed to be chastened. The victorious general returning in triumph to the imperial city had by his side an Auriga, who whispered in his ear, memento mori, “be mindful that you are mortal, that you are but a man.” In Gilson’s judgment, the Catholic Church was the Auriga of humanity.

The third and last challenge was found in Western Europe, where a new effort at cooperation and community was being born. Post-war Catholic statesmen such as Robert Schuman and Alcide de Gaspari had vowed that rivalrous nationalisms would not be allowed to rend the old cape again and draw the rest of humanity into a third world war. One thus saw the beginnings of a new Europe, one inspired by Christian Democratic principles, in the Congress of Europe (1948) and the European Coal and Steel Community (1952).

Gilson himself attended the Congress of Europe. He calls it “the first visible effort to realize this dream [of a united Europe].” His historical studies of the “dream,” starting with the medievals Roger Bacon (1219/20-1292) and Dante (1265-1321) and continuing with the moderns, allowed him to comment on the contemporary endeavor.

Of particular interest is a chapter entitled “The Birth of Europe” devoted to the thought of a remarkable figure, l’Abbé de St.-Pierre (1658-1743). “United Europe was born in France about two hundred and fifty years ago” with him. It was he who proposed a Project to Achieve Perpetual Peace in Europe.

Taking issue with Hilaire Belloc’s famous dictum that “Europe is the Faith and the Faith is Europe,” Gilson pointed out that it isn’t true. There was much faithful Christianity outside of any conceivable European region. Defining Europe by its Christian character thus runs into what we could call “the problem of excess.” Taking his cue from this observation, he further noted that while Europe has invented or developed any number of “universals” in the sciences, law, morality, technology, and political organization, precisely because they are universals, it cannot simply claim them as its own, as “defining it” to the exclusion of other civilizational regions.

When Europe attempts to reflect on itself and formulate its own essence, it tends to be dissolved in a broader society than itself, for which in fact it recognizes no other limits than those of the globe. Accustomed as Europe is to appeal to universal values, here peace through law, the justification that it gives of their outline abolishes Europe’s boundaries at the same time. Europe is so constructed that it is buried along with its triumph each time it tries to define itself.

In a striking formulation, he affirmed that whatever “body” a future Europe may give itself, its “soul” will always be in excess.

In his last chapter, Gilson summed up this line of thought and offered a final caveat:

Whatever its form may be some day, Europe can never be more than a geographic, political, and social reality, even if the people who compose Europe should be as fruitful in spiritual accomplishments in the future as they were in the past… We [will] know what Europe is when we know its structures and political frontiers. It will always be dangerous to hold up this real Europe as a sort of temporal Church, creator and possessor of a kind of universal truth that alone can unify humans… The more firmly we want a political Europe, the more it is important not to make it into a spiritual chimera.

In Gilson’s view, “to make Europe” (faire l’Europe) posed a particularly delicate task of “conjugation,” of combining body and soul, universals and particulars. Moreover, it was the work of politics to give it a “form” or “structures” (e. g., “political frontiers”) that would allow for this operation to be effectively conducted. Otherwise, a “spiritual chimera” would substitute for “reality,” for a “real Europe.” Gilson duly noted the presence of Winston Churchill, the political man par excellence, at the Congress.

With the Project of l’Abbé de St.-Pierre, Gilson was halfway through the series of “metamorphoses” he intended to study. Looking at the entire series, “if a lesson emerges about the history of the City of God and the avatars it has assumed during the course of the centuries, it is, first of all, that it cannot be metamorphosized.” Here was a striking “lesson” indeed! Pointedly, Gilson called these purposed realizations “parodies.”

To take a subsequent example, in Kant’s conception of Nature’s telos and of History’s culmination for humanity, which, following the Abbé de St.-Pierre and Rousseau, he called “perpetual peace,” “the naturalization of the City of God is complete.” Nature and History replace God and grace in effecting a peace that perdures. Kant thus summed up a “first wave” of modern naturalizations or “terrestrializations” of Augustine’s thought, what Carl Becker called “the Heavenly City of the Eighteenth-Century Philosophers.” He would not be the last, however, and some of his successors were even clearer in their parodic intent. Auguste Comte (1798-1857) was the prime instance.

Comte boldly advocated a new “religion of Humanity.” In it, a human race come of age would self-consciously replace the Christian God as “the Great Being.” Comte took it upon himself to specify in great detail the new “religion of Humanity” that would result, aping Catholicism in so doing. Europe had a special role in Comte’s rendering of human history, as the first sketch and avant garde of a reconciled Humanity. In all this, he followed and radicalized his modern predecessors, now making everything the work of History and of a self-adoring Humanity.

At the end of his exposition of Comte’s thought, Gilson takes the opportunity to offer some synthetic reflections. This is appropriate because

this time the experiment has been carried out with such perfect rigor that it can be considered conclusive. If the universal society, born of religion, returns to religion in August Comte’s Positivism, it is because between Augustine and Comte everything else has been tried in turn and tried in vain. … [Nothing] provided the universal society with the necessary bond that the Christian wisdom of faith had immediately offered it from the time of Augustine. It remains for us to draw a lesson from this experience that is already twenty centuries old.

The lesson bears directly upon the first challenge limned above. In formulating it, Gilson applied an old legal and, more broadly, practical maxim: Qui vult finem, vult media quoque. He who wills an end, wills the means as well. Or at least, he should will them.

It may be, and this would not be the only case, that in seeking a universal society by the sole paths [voies] that humans without God dispose, our contemporaries desire a Christian end without desiring the Christian means. The lesson would be simple, therefore: unless we resign ourselves once more to the false unity of some empire founded on force or of a pseudo-society without a common bond of minds and hearts, it is necessary either to renounce the ideal of a universal society or to seek again the common bond in Christian faith.

Contemporary proponents of a unified humanity must make a fateful decision. To attain their goal, one that modern history has done much to realize, they must not only will what history currently proposes, but what the Church has always proposed. It is as though history were working for apologetic purposes. This, at least, is how Gilson, the Catholic historian, presented matters.

Given in 1952, speaking to a Catholic audience, Gilson’s lectures expresses the self-understanding and self-confidence of pre-Vatican II Catholicism (or a dominant strand thereof). Confident in the adequacy of its own intellectual resources, it confidently looked upon the world; and it was supremely confident in what it offered—itself and its truths—to a divided humanity. This, of course, is not the whole story of pre-Vatican II Catholicism! But whatever larger story one tells, this self-understanding and self-confidence should be recognized. It belies the legend of a pre-Vatican II “fortress mentality.” And looking forward in time, grasping this moment is important in order to take the measure, for good and for ill, of Catholicism after the Council.

Likewise, one can use Gilson’s historical studies, and his treatment of a dawning united Europe, to help evaluate subsequent developments. Earlier, I noted that Gilson invested politics and its practitioners with the task of forming a “real Europe,” a “political Europe.” Nothing, however, guaranteed that after the founding generation, subsequent European politicians would be up to the task, or conceive it as did their predecessors, who were forged in different circumstances, with many formed by a confident Church.

Gilson also insightfully pointed to the place, role, and temptation of “the universal” in European history. He thus invites us to consider, what universal, or universals, were invoked as Europe developed, as it was subsequently constructed? He would also have us ask, what relationship will it (or they) have to Europe’s developing “body,” and to “the particulars,” the individual member-nations, that compose it?

The contemporary French political philosopher, Pierre Manent has addressed these questions during a life time of work. Here is not the place to go into it, much less provide a summary. But on a central point, Gilson’s book is of great relevance.

According to Manent, at a certain point (he indicates the ratification of the Maastricht Treaty in 1992), European elites opted for a version of the religion of Humanity. In so doing, they rejected the Christian faith and understanding of democracy of the Christian Democratic founding fathers and opted for Comte’s atheistic-humanistic “dream.” With them, his “spiritual chimera” became European reality and even surreality. From Manent’s point of view, Gilson’s chapter on Comte has important contemporary relevance.

Important relevance, but not complete adequacy. Because of the contemporary EU’s unique configuration as an “institutionalized chimera”—at once real, surreal, utopian, and ideological—a new chapter needed to be written in the history of European metamorphoses of the City of God. As history moved on, and the historian went to his eternal reward, the political philosopher took up the torch.