Forgetting the Fall

Exhortations to reorient American politics toward the common good abound. This rhetoric revives a long American political tradition of reasoning that emphasizes our duties more than our rights. Such reasoning offers a valuable corrective to decades of liberal theorizing that tended to ignore the common good. Yet one curiosity concerning these appeals to the common good is their tendency to avoid discussing the pressing challenges that undermine them—and they especially seem to ignore the limits that human frailty, ignorance, and vice impose on doing good in public life.

It was not always thus. Historian Robert Tracy McKenzie’s We the Fallen People attempts to understand the shift from a republican polity founded on an understanding of human flaws to a democratic nation perpetually forgetting the proper limits of politics. He focuses on two periods of American history: first, the republican years immediately before and after the adoption of the U.S. Constitution; second, the Jacksonian Era and the rising tide of democracy. His thesis is unusually theoretical for a historian: “We must renounce democratic faith, our unthinking belief that democracy is intrinsically just. We must disavow the democratic gospel, the ‘good news’ that we are individually good and collectively wise.”

McKenzie demonstrates the degree to which the United States was founded with the dangers of our fallen nature firmly in mind, yet his very emphasis on theory distorts his vision not just concerning our past, but our present politics as well.

What Rules Men’s Hearts

In Federalist 51, James Madison referred to justice as the end of civil society and of government itself, something that people will always pursue “until it be obtained, or until liberty be lost in the pursuit.” When fallen people pursue justice, they are tempted to avoid moderation and wreak vengeance on those they see as wrongdoers. Yet despite this danger, Madison knew that a shared attachment to justice was vital to the republic. Great concerns of justice and the general good, he believed, were the only grounds upon which coalitions involving a strong majority could be built in an extended republic. As no shared ideal or interest bound Americans together deeply enough, he was skeptical about how long any such majority could hold.

McKenzie contends that arguments like Madison’s formed the background for the American Founding. But so also did the nation’s relatively strong Christian faith. Americans attended church in large numbers in this period—one estimate holds that between 71-77% of the population regularly attended a church in 1776. Despite wildly divergent theologies, what was common among them was a skepticism concerning the limitations of human nature. They generally shared a belief that our individual ability to consistently behave morally was quite limited, and that the pressure of public opinion further compromised that low capacity for virtue: “The problem as they understood it is not that we’re wholly evil; it’s that we’re not reliably good.” McKenzie argues this stance was a core part of their views; one might go so far as to suggest it was an essential part of the nation’s Cultural Christianity.

By and large, the observations with which Madison concludes Federalist 55 hold here, “As there is a degree of depravity in mankind which requires a certain degree of circumspection and distrust: so there are other qualities in human nature, which justify a certain portion of esteem and confidence.” Madison continues in a manner important for McKenzie’s point:

Republican government presupposes the existence of these qualities in a higher degree than any other form. Were the pictures which have been drawn by the political jealously of some among us, faithful likenesses of the human character, the inference would be, that there is not sufficient virtue among men for self-government; and that nothing less than the chains of despotism can restrain them from destroying and devouring one another.

In general, then, McKenzie concludes that “the Framers scoffed at the contention that men and women are basically good, but they also rejected the view that we are relentlessly depraved.” Even Reformed thinkers like John Witherspoon would concur with the politics this produced—but in doing so they would point to the works of God rather than those of man as the source of that residual confidence.

Crafting a nation’s fundamental laws around the fact that “enlightened statesmen will not always be at the helm” is not the same as assuming like David Hume did that “every man ought to be supposed to be a knave.” While Hume’s position might offer a justification for indifference to politics, the founders’ notion here results in a guarded view of politics and skepticism toward all forms of power without denying the possibility that good statecraft is possible: “The Framers grounded the Constitution on the assumption that power predictably corrupts our behavior.”

Pursuing the Public Good

McKenzie shows how the Founders viewed the role of legislation: “A dedicated public servant would be characterized by a zeal for the public welfare, not by a slavish obedience to the public’s preference.” They shared a skepticism for directly involving large numbers of people in politics. The people at large are not good judges of character:

This was not a commentary on their innate intelligence or their moral character but rather a recognition that few Americans in the late eighteenth century possessed the education, information, and time for study required to make informed decisions about national politics.

Neither the people nor their leaders are immune to temptation: Benjamin Rush wrote that “the people are as much disposed to vice as their rulers.” This observation and many others like it drove the Framers’ understanding of political life: “Because none of us is naturally virtuous, because we’re all subject to the lure of self-interest, because each of us is vulnerable to the intoxication of power, power is always a threat to liberty,” regardless of who wields it.

Under these conditions, the pursuit of the public good would be marked by discussion and compromise, reflecting a moderated conception of what majorities of representatives from across the young nation could be persuaded to accept.

The Framers knew there would be no angels in the government, and no angels in the electorate, and they planned accordingly. They designed a Constitution for a fallen people. Its genius lay in how it held in tension two seemingly incompatible beliefs: first, that the majority must generally prevail; and second, that the majority is predisposed to seek personal advantage over the common good.

It is impossible to prove what percentage of those men who debated and ultimately ratified the Constitution believed the Christian teaching of original sin. Some, like Thomas Jefferson, we can say fairly conclusively did not. Many leaders of the period left us little or no comment on their own faith. McKenzie suggests that it is more crucial that they crafted the laws and argued in terms that deeply resonate with this teaching. Whatever their individual intentions, we can look back and see that they worked “to design a framework of government for people who would be fallen as well as free.”

These men could rely on a Christian culture to help reinforce a sense of skepticism toward concentrated power and the widespread perception that too vigorously pursuing a single state or social group’s idea of justice, prosperity, and order would lead to factionalism and disunion. What is striking about McKenzie’s account is how he argues that this tempered realism and the Cultural Christianity that supported it shifted quickly away from a thoroughgoing commitment to accepting the political consequences of the fall.

The Triumph of Popular Sovereignty

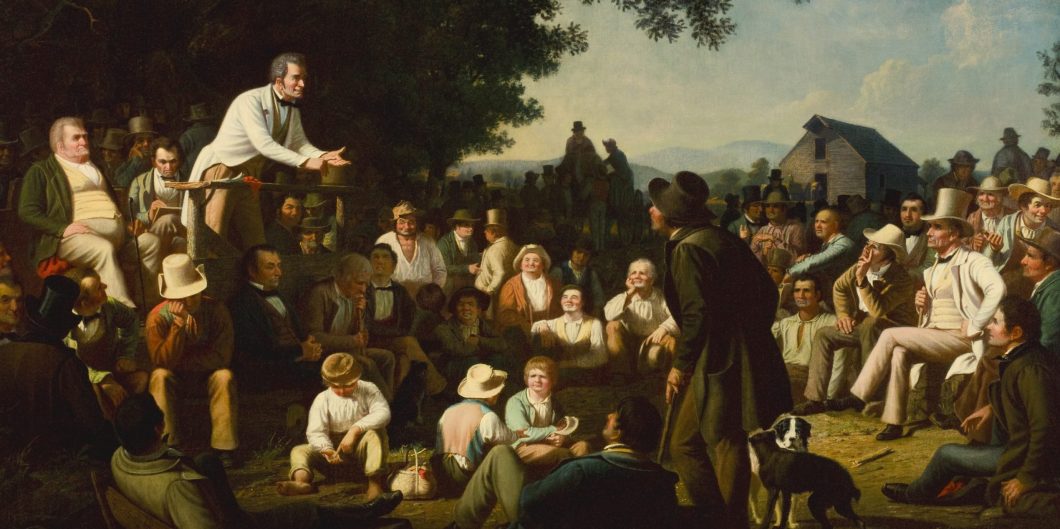

History remembers the election of 1824 most for the “Corrupt Bargain” and its accusations of trading support for political office. Despite Andrew Jackson’s defeat in that election, McKenzie presents a compelling case that it is this campaign that accelerates the collapse of the old republican ideal and the beginning of a new form of self-assured democracy.

Jackson’s presidency did not just inaugurate a new way of thinking about executive power, with his conception of the executive branch as an independent source of authority, able to act in ways that were hitherto unthinkable in the people’s name. It marked something greater, in that it revealed a profound shift in how Americans thought about politics: “The will of the people ‘is our oracle,’ Jacksonian writer George Bancroft proclaimed the year after John Quincy Adams entered the White House. ‘This, we acknowledge, is the voice of God.’”

The era’s greatly increased confidence in the judgment and moral capacities of the people is quite novel, McKenzie argues. Andrew Jackson preached a democratic gospel that assured “Americans that democracy was not a rejection but a fulfillment of values inherited from the Founders, most particularly their faith in the innate virtue of the people.” Jackson “was justifying a new democratic mindset by appealing to an understanding of human nature that the Framers roundly rejected and Christian teaching had long rejected.”

This new mindset erased the suspicion with which the Founders viewed political life. It also shifted how Americans perceive the democratic process as a whole:

Our modern democratic ethos presupposes that we are individually good as well as collectively wise in our political choices. From this it logically follows that losing candidates deserve to lose, at least when the system is functioning as it should. If the electorate is both virtuous and discerning, then losing candidates face one of two options: either acknowledge that their opponents genuinely deserved to win or point to real or alleged abuses of the system that prevented the voice of the majority from being accurately registered. What they can’t do—unless they’re bent on political suicide—is blame the majority for making a bad decision.

One consequence of this ethos is the way it encourages and deepens partisanship by eliminating the old suspicion against popular enthusiasm.

Using lengthy case studies of the Cherokee Removal and the debate over the Bank of the United States, McKenzie explores the contours of this new democratic faith, and sets these alongside Alexis de Tocqueville’s observations of American democracy at work. Throughout, he emphasizes the ways that Tocqueville extended the Founders’ view that self-interest could be productively channeled to maintain republican liberty—and highlights the ways that Tocqueville could not share in his American hosts’ judgment of their own goodness and their ability to judge political events and actors wisely. But it is this blending of theory and historical analysis where the book’s most important missteps occur.

While McKenzie’s theoretical account of the consequences of such a corrupted faith is sound, he appears at times to read backward all too many of his own fears about our present republic’s fragility into Jacksonian America.

Populism and the Elites

We the Fallen People offers a warning to those who would seek the common good without reckoning with our fallen nature, and historical lessons about where a misplaced faith in democracy ultimately leads. The book also offers an example of what can happen when we subordinate our interpretations of history to present political concerns.

As a work of historical reconstruction and analysis focused on the Founding, We the Fallen People follows well-trodden ground. McKenzie uses that era’s thinkers in service of his argument about how human nature shapes politics, and how the American political culture’s rejection of original sin has corrupted our public life. While McKenzie’s theoretical account of the consequences of such a corrupted faith is sound, he appears at times to read backward all too many of his own fears about our present republic’s fragility into Jacksonian America.

Indeed, McKenzie’s account of the Jacksonian era too readily assimilates Jackson’s politics—which might plausibly be understood to carry forward echoes of Thomas Jefferson and other power-skeptical founders—to those of our day’s own populism. He writes:

Populist movements… are regularly drawn to strong leaders who promise to clean house and make the government more responsive to the people. While the Founders would teach us to be suspicious of power as a threat to liberty, populism teaches us to have faith in power, as long as it’s exerted on behalf of the people by the champion of the people.

But it isn’t just those convinced by populists on the left and right that succumb to this temptation. McKenzie’s argument suggests that many Americans approach politics in a way that broadly rejects original sin at least in their assessment of public life, but he hesitates to move beyond populism, applying his critique to everything in our political life.

McKenzie argues that populists, perhaps uniquely, tend to think in dichotomies that pit the “true people” against the “false people.” The trouble here is the degree to which the book ignores the way that in the last few years, elite discourse in the United States has followed similar tendencies. This phenomenon intensified with Covid’s exhortations to “follow the science” or be consigned to ignorant darkness. The elite discourse surrounding Covid exemplified faith not in democracy but in the superior wisdom of elites—and demanded that in the name of public health we should abandon any skepticism toward unchecked power.

In a certain sense, the most Jacksonian thing we can do in modern American politics would be to reject the centralization of power whether wielded by the hands of elected officials or the myriads of non-elected “experts.” The irony McKenzie misses in Jackson’s politics is that while his administration did rely on the use of a new conception of executive power to achieve its goals, he did so in service of undermining federal authority over banking, and in the name of the Founders’ Constitution. McKenzie’s horror at modern populism leaves him with a deficit of the sympathetic understanding that good history often requires. It renders him unable to paint a more human picture of how an immoderate skepticism toward elites naturally falls into conflict with an equally immoderate distaste for the ordinary citizen.

McKenzie presents a compelling case that many Americans lost what residual skepticism they maintained toward power but forgets this is a permanent challenge and not one we can blame on one generation’s loss of understanding what sin means for political life. While it sometimes presents a flawed history, We the Fallen People does offer a lesson in political theory that will naturally encourage readers to condemn both the excesses of populism and trust in elite administration. This reminder bears special importance in our present debates about what role the common good must play in political life. We are always tempted to forget our own limits, where a focus on the fall ought to lead us back into a realism about ourselves, our politics, and the justice we seek together.