Impeachment was designed with the idea in mind that presidents sometimes might warrant removal from office, and this might flow from many causes.

Founding Philosemitism

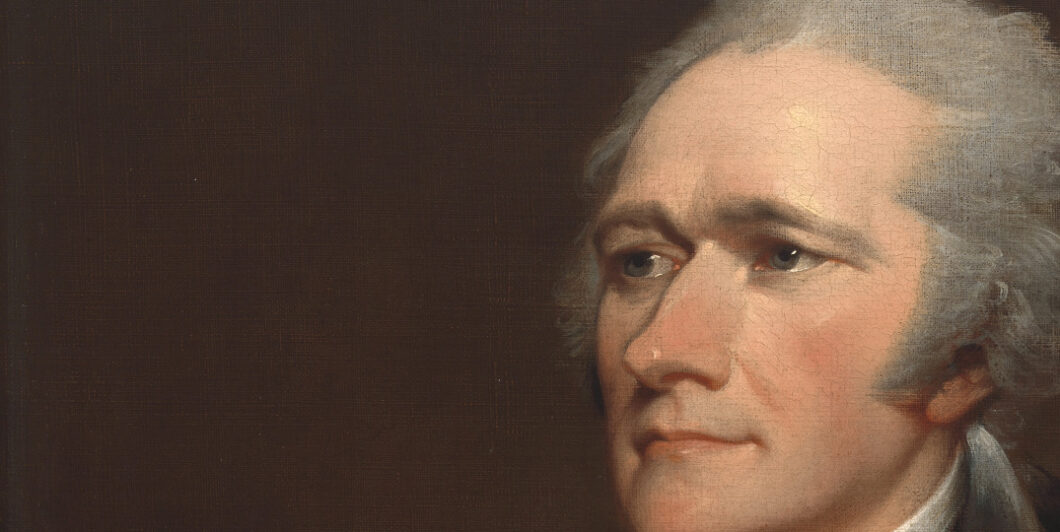

Who else but Alexander Hamilton could have inspired the most successful Broadway musical ever produced about the Founding? The penniless kid who would become a political superstar was the ideal protagonist for a show whose infectious vitality rekindles enthusiasm for the American experiment, a potent antidote to today’s culture of grievance. Born out of wedlock on an island in the British West Indies, a strong believer in Providence who never joined a church, Hamilton’s role in advancing the cause of civil and religious liberty is worth revisiting in a new light.

University of Oklahoma Professor Andrew Porwancher does just that, masterfully. In The Jewish World of Alexander Hamilton, he addresses the paradox of a nation “conceived in the name of equality yet defined by hereditary hierarchy—free over slave, white over Native, propertied over landless, man over woman, Christian over Jew.” American Jewry was the one minority that balked, “challenging the country to confront this paradox directly,” invoking the Declaration of Independence to demand civil and religious rights. Hamilton knew this, which is why Porwancher directed the scholar’s stage lights on him, offering “a unique window onto the early American republic writ large.”

While “Hamilton sought an economic and legal order where his Jewish compatriots would stand equal to their Christian neighbors,” it wasn’t just about the Jews. Hamilton understood that standing up for one minority would “illustrate the democratic possibilities of the new nation.” Like his fellow Founders, his commitment to liberty was based on philosophical principles. But it helped that Hamilton had also witnessed the evils of racism and antisemitism while growing up poor on the periphery of civilization.

True, philosophical principles are paramount. It is no small irony that of all the Founders, the greatest animosity toward Jews and Judaism was displayed, albeit privately, by none other than the author of the Declaration. “The whole religion of the Jews,” Thomas Jefferson told a Christian protégé, was based on “the fumes of the most disordered imaginations” masquerading as “special communications of the Deity.” John Adams described Jews as “avaricious,” as did Benjamin Franklin, who thought greed to be entrenched in the Jewish psyche.

Yet they both expressed great admiration for the Hebrews. Adams declared them to have influenced the affairs of mankind more, and more happily, than any other nation, ancient or modern, going even so far as to describe them as “the most glorious Nation that ever inhabited the earth.” Franklin also exhibited an “inconsistent mix of bias and tolerance toward Jews and their faith.” (He always included synagogues among the beneficiaries of his donations to the building of houses of worship.) Franklin’s ambivalence, writes Porwancher, “made him typical of several other Founders.” Only George Washington’s utter “lack of prejudice against Jews was of a piece with Hamilton’s, although the former never developed the extensive ties to Jews that the latter would.”

The partnership of these two epic figures seems all but preordained. The diminutive Hamilton’s filial devotion was reciprocated by the towering General’s fatherly affection and cemented their extraordinary professional bond. Washington had been looking for “a man of courage with learning, wisdom, and experience, who could ‘think as well as write for him,’” when the military hero who led his troops to victory at the battle of Trenton and Princeton in 1776 caught his eye. Having joined the local militia while studying at New York’s King’s College on a scholarship, Hamilton’s martial savvy complemented his intellectual skills. Plus he had street smarts to boot. Washington invited him to become his aide-de-camp, promptly promoting him to lieutenant colonel.

And advise the General he did, specifically concerning a Canadian Jewish merchant and president of the oldest synagogue in Montreal, David Salisbury Franks. Staunchly opposed to the British, Franks had left Canada to join the Continental Army. As a major, he was soon appointed aide-de-camp to General Benedict Arnold, only to fall under suspicion when the latter defected. Arnold categorically denied that Franks had known anything about the plot, but the widespread presumption that Jews were shifty and untrustworthy might have swayed a military tribunal against him. Hamilton knew this as well as Franks. Thus, ghostwriting for Washington, he advised Franks to seek acquittal through a civil court.

Though exonerated by the military, Franks eventually did request a civil trial to clear his name—and succeeded. Quickly promoted, he was immediately entrusted by General Washington to carry highly secret documents to Franklin in Paris and to Jay in Madrid. In 1783, he returned to Philadelphia, then journeyed to Paris to deliver the official copy of the peace treaty that ended the war and granted American independence. After the war’s end, Franks was named envoy to France and then Morocco, thereby becoming the first Jewish diplomat in American history.

Hamilton was also involved in another first. In 1787, he took up the cause of his alma mater, King’s College, renamed Columbia, whose 1754 charter had just come up for renewal. The New York State legislature wanted to wrest control from the board of trustees, but Hamilton was instrumental in thwarting that plan. The charter was also updated to explicitly revoke the administration’s power to “prescribe a form of public prayer.” It even abolished any requirements “which render a person ineligible to the office of president of the college on account of his religious tenets.” A new trustee was also named to Columbia’s board: Gershom Seixas, a Jew. “Seixas and Hamilton had previously sat together on a board of regents that oversaw education writ large in the state of New York,” writes Parwancher, “but now—for the first time since higher education began in America with the founding of Harvard in 1636—a Jew would serve as a trustee of a specific college. Columbia would not have another Jew on its board until 1928.”

Hamilton introduced Seixas to the upper echelons of New York Society. The first American-born hazzan (cantor and prayer leader) anywhere in the colonies, he was already well known, having gained national stature in 1776. As British troops prepared to invade Manhattan, Seixas fled the city carrying with him Torah scrolls. Besides assuring the safety of the sacred parchments, explains Porwancher, the brave act was “a symbolic gesture of his belief in the providential blessing for the Patriot cause.” In 1780, Seixas arrived in the City of Brotherly Love, where he became hazzan of its congregation, Mikveh Israel.

Hamilton always deeply believed, as would Lincoln in the next century, that the same providential protection that kept the small Jewish world alive, while so many other civilizations became extinct, would embrace his own extraordinary nation, despite great challenges.

At a time when most states ignored the Declaration and continued to place restrictions on the civil participation of Jews alongside other minorities, Pennsylvania placed religious barriers to holding public office only on atheists and polytheists. Yet even there, fears were common that “Jews or Turks [i.e., Muslims] may become in time not only the greatest landholders but principal officers in the legislative or executive parts,” which would render it outright “unsafe for Christians.” But of all three million Americans, only one protested: the former president of Mikveh Israel and a war veteran, Jonas Phillips. He decried the distance between the promise of the Declaration and the prejudicial reality of the early republic and petitioned the Constitutional Convention which had just convened in his city. The year was 1787. Coincidentally, at the same time Seixas, now returned to New York, became trustee of Columbia.

What Phillips could not have known, the Convention’s proceedings being secret, is that a week earlier the delegates had already adopted Article VI, section 3 of the Constitution. It read: “No religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or public trust under the United States.” Later that same year, it was adopted, thanks in part to Hamilton’s tireless efforts on its behalf—especially in his own state, which was deeply divided on the issue. His reputation as “the premier promoter of the Constitution” was demonstrated by the parade organized to support its ratification in New York City on July 23, 1788. His personal influence indicated the appeal of Federalists to the working man. “New York’s tradesmen, who marched in the parade grouped by profession, considered Alexander Hamilton to be the human embodiment of the Constitution,” writes Porwancher. “The sailmakers unfurled a flag with a depiction of Hamilton at its center. Grain measurers, too, displayed a flag, featuring the likeness of Hamilton on one side and of George Washington on the other.”

It is no coincidence that the parade, originally scheduled for July 22, had been moved by one day to accommodate a Jewish holiday marking the fall of Jerusalem in 70 AD. The Jews’ negligible numbers aside—they comprised only some 1 percent of the city’s population—Hamilton’s support for respecting their religious tradition appealed to ordinary folks of all ethnicities.

But even after the Constitution was ratified, most states continued discriminating on religious grounds. As before, it affected all minority faith groups; and again, it was a Jew who protested: Moses Seixas, the older brother of Gershom Seixas, Hamilton’s friend. The warden of Newport’s Tuoro Synagogue and member of the King David Masonic Lodge, Moses greeted the president on August 17, 1790, to express his gratitude for living under “a Government, erected by the majesty of the People.” The rest of his eloquent talk made a profound impression on Washington, as the letter he would pen to the congregation on the following day manifestly demonstrated.

The letter affirmed that in America, “it is now no more that toleration is spoken of, as if it was by the indulgence of one class of people, that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights.” The greatest surprise came in the next sentence, when Washington, like Seixas, praised “the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance—but generously affording to all liberties of conscience, and immunities of citizenship.” The President had used Seixas’s words verbatim. And he added that it “requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens.” Never did plagiarism offer its victim as well as his audience greater satisfaction.

“The Newport letter stands as close to a formal emancipation of the Jews as can be found in the history of the presidency,” observes Porwancher. For Hamilton knew well the larger, universal context. In an undated jotting preserved in public archives, Hamilton had expressed wonder:

at the progress of the Jews, [who] from their earliest history to the present time has been & is, intirely [sic] out of the ordinary course of human affairs. Is it not then a fair conclusion that the cause also is an extraordinary one—in other words that it is the effect of some great providential plan? The man who will draw this Conclusion will look for the solution in the Bible. He who will not draw it ought to give us another fair solution.

Although attending a yeshiva was traditionally restricted to Jews, evidence that Hamilton might have been Jewish is at best circumstantial. Never mind that, according to Porwancher, “many of [Hamilton’s] adversaries weaponized antisemitism against his various endeavors throughout his career.” Hamilton, who described himself as a Christian, simply believed, as would Lincoln in the next century, that the same providential protection that kept the small Jewish world alive, while so many other civilizations became extinct, would embrace his own extraordinary nation, despite great challenges.

America, too, affirmed and enforced—even if belatedly and often unevenly—the principle that all humans were endowed by their Creator with inalienable rights to liberty. Extraordinary, it could also be called exceptional. Perhaps even chosen. Or at least, as Lincoln put it, almost chosen.