Genosuicide and Jewish War Ethics

In Ethics of Our Fighters: A Jewish View on War and Morality, Rabbi Brody’s learned and sensitive review of the ethical problems that confront the Jewish State in its long war against terrorists embedded in civilian populations bears a 2024 publication date, and its Acknowledgements page is dated by the author as October 2023. The manuscript was obviously submitted before October 7, so there is no mention of the Simchat Torah massacre. Hamas’ attack on Israel, which killed more Jews than on any day since the Holocaust, and perpetrated atrocities worse than those of the Nazis, makes Brody’s examination of Jewish law all the more relevant, but less than complete.

Israel’s subsequent campaign in Gaza has elicited accusations of “genocide” from the government of South Africa, the president of Brazil, and Muslim activists in many parts of the world. These accusations can be answered with one observation. An American-led coalition consisting mainly of Iraqi forces destroyed the city of Mosul in northern Iraq in 2017, with civilian casualties estimated by different sources between 9,000 and 40,000. The Associated Press count was 11,000 civilians dead but it might have been much higher. ISIS fighters prevented civilians from leaving as the US and its allies bombarded the town, and no one knows to this day how many are buried under the rubble. Mosul had 2 million inhabitants, about the same as Gaza, and the civilian casualties ensuing from a campaign to extirpate terrorists using the population as human shields are comparable. Yet Internet searches find not a single accusation that the US coalition had committed “genocide” against the civilian population. Under similar conditions, and with comparable casualties, it occurred to no one to speak the G-word.

What we learn from Brody’s account is that the Jewish State has agonized over the rules of war and the treatment of civilians more profoundly than any policy in history. Although Israel’s secular government is not legally bound to Jewish religious law, rabbinic interpretation of divine command ethics remains a decisive factor in Israel’s policymaking.

Jewish law, or halakha (“the way”), was codified in the early centuries of the Common Era by the sages of the Talmud in Palestine and Babylon, and elaborated by generations of later scholars, grouped loosely into early commentators (“Rishonim”) such as Maimonides (1138–1204) and Nachmanides (1194–1270), and later (post-sixteenth-century) authorities (“Aharonim”). The more ancient sources carry more weight, and any ruling in religious law must begin with precedent. Brody’s title, “Ethics of Our Fighters,” is a gesture to that tradition, referring to Pirkei Avot, “ethics of our fathers,” a tractate of the Mishnah (the oldest section of the Talmud).

In 1982, Brody reports,

Lebanon was supposed to now fall under the control of Bachir Gemayel, a Christian Lebanese militia commander of the Phalange Party who had been elected two weeks beforehand as president of Lebanon’s National Assembly. Gemayel was supported by the Reagan administration and Israel’s government, who saw him as an ally who could sign a peace treaty with Israel. On September 14, however, Gemayel was assassinated. A couple of days later—on the Jewish New Year, Rosh Hashana—Phalangist militiamen took revenge for his death by killing or wounding thousands of residents in the Palestinian refugee camps Sabra and Shatila near Beirut. Israel established a government inquiry. It found that Defense Minister Sharon and the IDF chief of staff were “indirectly responsible” for the massacre. They should have known it was going to happen and could have taken steps to stop it once it started.

The incident provoked anguished division among Israel’s religious Zionists. Israel’s Chief Rabbi Shlomo Goren, the country’s most prominent halakhic authority, and others “were against Israel’s investigation and tried to stop it from happening. They believed that Israel was being scapegoated for actions it didn’t commit. Accepting any responsibility would only lead to international antisemitism. Where was the international outrage when the Lebanese factions were slaughtering each other during their extended civil war in the 1970s?”

Other religious Zionists including Rabbi Yehuda Amital and Rabbi Ahahon Liechtenstein supported the investigation. The perpetrators “weren’t random Christians,” Brody observes. “They were the IDF’s allies.” For this reason, R. Amital deemed the event an enormous ĥillul Hashem [desecration of the Divine Name] and castigated religious Knesset members for not supporting the government inquiry. His colleague R. Lichtenstein, in an open letter to Prime Minister Begin, asserted that national honor could be restored only through investigation and introspection. This call was echoed in America by R. Lichtenstein’s father-in-law, Rabbi Soloveitchik, who pressured religious members of the Israeli cabinet to support the inquiry, as well as Britain’s chief rabbi, Immanuel Jakobovits, who deplored the “dishonor done to the Jewish name.”

Brody concludes, “R. Amital and R. Lichtenstein were right, but it’s important to understand why. The residents of Sabra and Shatila were noncombatants who could not be directly targeted under Jewish ethics. They were murdered by Israel’s allies and under the IDF’s noses for the sole purpose of vengeance.” But it was Chief Rabbi Goren who ruled that as a matter of Jewish law, the IDF was obligated to give both enemy combatants and civilians the chance to flee a siege.

Jewish law, [Goren] declared, requires Israel to allow both combatants and noncombatants to flee a besieged city. This stemmed from the opinion of a second-century rabbinic Sage, R. Natan, followed by Maimonides, who ruled that the “fourth side” of a city must always remain open. The logic was twofold. Strategically, this will give combatants an incentive to flee; otherwise, they might fight to the finish, at great cost to both sides. On a humanitarian level, moreover, it is important to show mercy during war, even to our enemies.

I am not conversant with medieval rules of war, but I can find no reference to a comparable injunction about the combatants as well as the inhabitants of a besieged city—and this from a Jewish authority writing in Muslim Egypt, whose people had not had a state or an army during the preceding thousand years.

A vastly different logic applied to the accidental 1982 bombing of a civilian compound at Qana where Hezbollah terrorists had taken refuge after firing missiles at Israeli forces, Brody reports. Over a hundred civilians died. Brody cites Matan Vilnai, then the IDF deputy chief of staff, who argued, “Hezbollah are doing their utmost to get civilians killed by sheltering among them and by firing Katyushas and mortars from positions very close to UN or civilian positions.” As Brody explains, “In 1982, the Phalangists targeted noncombatants when they were under no immediate threat. It was revenge, not self-defense. In 1996, the IDF was trying to destroy rockets that were threatening their fellow soldiers. The non-combatant deaths were unintentional and were caused by Hezbollah shooting next to the UN shelter.”

Israel takes greater precautions than any country in the world to minimize civilian casualties. Brody writes:

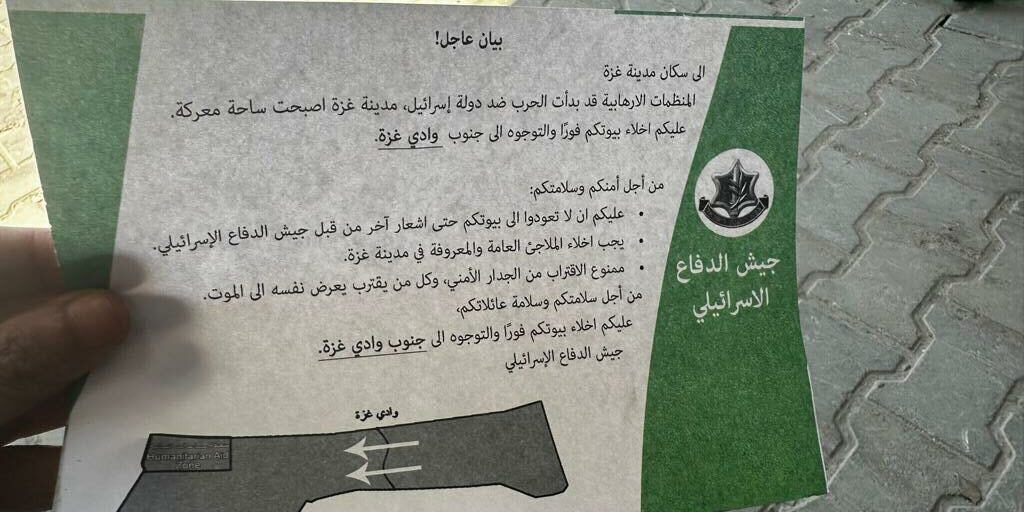

The IDF pioneered in 2008 a technological method for more pinpoint warnings. Israeli soldiers would call Gazans’ personal cell phones and warn, in Arabic, “This is the Israeli military. We need to bomb your home and we are making every effort to minimize casualties. Please make sure that no one is nearby since in five minutes we will attack.” Such calls frequently got the residents to leave. Yet some residents would not go. So the IDF developed the so-called “roof knocking” technique. The Air Force would drop small, empty missiles over the buildings. Sometimes they would explode above the roof; other times, they blew up upon landing but caused minimal physical damage. Either way, a horrific boom would fill the air. Terrified residents would now flee the building. After waiting a few minutes, the air force would then drop a more powerful missile. The target was destroyed, but casualties were limited.

Brody comments, “Morally speaking, ‘roof knocking’ is an updated version of the ‘fourth side open’ imperative to get people to flee.”

Rabbi Brody’s book helps us understand why Israel’s actions in Gaza—despite the most extreme sort of provocation—remain bounded by ethical constraints that derive from Jewish tradition.

The trouble is that the terrorists of Hamas and Hezbollah are a phenomenon that the rabbis of antiquity and the Middle Ages never encountered. Never before in the annals of warfare has a combatant sought to maximize civilian casualties among its own population, the better to rally humanitarian sentiment in its favor. Hamas had no illusions that its 40,000 lightly armed fighters (before October 7) could engage Israel’s 170,000-strong regular army backed by 300,000 reservists. By committing unspeakable atrocities on a large scale, including multiple rapes and the murder of small children, and then using civilians as human shields, Hamas hopes to persuade the international community to impose a settlement on Israel that would give it better ground for a fight—for example, a so-called two-state solution in which Hamas would inevitably control the Arab state.

Before the October 7 attack, for example, Gaza terrorists killed small numbers of Israelis by firing large numbers of low-quality rockets at Israeli population centers. In May 2021, for example, Hamas and Islamic Jihad fired more than 4,340 rockets at civilian targets in Israel. These rockets killed ten Israelis, but many rockets fell back inside Gaza. By Israeli estimates, the failed rockets killed more than 90 Palestinian Arabs. That is, Hamas and Islamic Jihad were willing to kill ten Arab civilians in order to kill one Israeli civilian. Whether the 10:1 ratio is accurate is moot: Arab civilians in Gaza faced greater danger from Hamas rockets than did Israeli civilians.

Call it “genosuicide,” the deliberate pursuit of a policy that puts large numbers of civilians in jeopardy to gain an advantage over an adversary. Emil Durkheim identified “anomic suicide” as the result of social disintegration, but he restricted his attention to individuals. Entire peoples can engage in suicidal behavior out of cultural despair. Hamas has undertaken the hopeless task of preserving a fundamentalist faith rooted in tribal society in the modern world. Its adherents would rather die than be metabolized into the bland soup of modernity. Small peoples have fought to the death against encroaching empires since the dawn of man, but never before under Klieg lights and news cameras, in a Grand Guignol theater of horror designed to overwhelm Western sensibility.

This is a new and horrible manifestation of cultural despair. The massacre of civilian populations in the course of war, to be sure, was an unexceptional event in ancient and medieval warfare, emphatically within Christendom itself, e.g., the Sack of Thessalonica in 1185, the 1209 massacre of Cathars at Béziers, or the 1631 Sack of Magdeburg. All of these were celebrated by the victors as righteous actions against heretics. Aquinas, the main medieval source for Just War theory, supported the extermination of heretics in the Albigensian Crusade, as Michael Novak reports. International humanitarian law was not encoded until the 1864 Geneva Convention. The conscience of the world barely fluttered over the murders of 1.5 million Armenians and half a million Greeks during and after World War I, let alone the extermination of six million Jews during World War II, not to mention up to 3.2 million killed and 18 million displaced in the India-Pakistan partition of 1947. The liberal world order that succeeded the Cold War, though, focused on human rights, culminating in the acceptance of “responsibility to protect” at the 2005 United Nations World Summit.

Hamas is gaming the system, fighting a war behind human shields that seeks to maximize civilian casualties—the better to appeal to the conscience of the international community and motivate intervention against Israel—and prepare the battlefield for new terror attacks.

That leaves Israel with the dreadful choice of endeavoring to destroy Hamas, incurring significant civilian casualties despite its best efforts to minimize collateral damage, or allowing Hamas to continue to operate after the murders of nearly 700 Israeli civilians, including 36 children, as well as the abduction of 250 Israelis as hostages. No state can tolerate terrorism on that scale and survive, and the Jewish State has no choice but to extirpate the malefactors. In terms of relative population, that is the equivalent of more than 30,000 American lives, or 9/11 tenfold. One can only imagine what the United States would do if Mexican terrorists killed tens of thousands of Americans in a cross-border raid.

By modern gauges of warfare, though, Israel’s operation against Hamas has been restrained. Even if the casualty numbers promulgated by the “Gaza Health Ministry,” that is, Hamas, are taken at face value, they imply (as Alan Dershowitz argues) “a ratio of civilians to combatants killed of roughly 2 to 1—that is, for every combatant killed, two civilians would have been killed. Israel’s record is far better than that of any other country in the history of modern urban warfare. If this ratio is close to being true, then Israel’s record is far better than that of any other country in the history of modern urban warfare facing comparable enemies and tactics. Typical ratios of civilian to combatant deaths range from 3 to 1 to 10 to 1, as in the cases of Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen, and Syria. And those ratios occur in situations where civilians aren’t used as human shields.”

Rabbi Brody’s book helps us understand why Israel’s actions in Gaza—despite the most extreme sort of provocation—remain bounded by ethical constraints that derive from Jewish tradition. And it helps clarify why the defamation of the Jewish State as a perpetrator of genocide is one of the most nefarious lies ever told.