Jews and the American Left

In her An Idea Betrayed: Jews, Liberalism, and the American Left, Juliana Geran Pilon, Senior Fellow at the Alexander Hamilton Institute for the Study of Western Civilization, has written a passionate defense of “the American creed,” comprised of the principles of liberalism in its original sense (as they are expressed in the Declaration of Independence and Constitution), combined with a lament at the failure of many of her fellow, contemporary American Jews to appreciate those principles. Having spent her childhood in Communist Romania under the Ceausescu dictatorship before her family was allowed to emigrate, and thus having personally experienced the contrast between free, constitutional governance and its opposite, she is dismayed to find our creed under attack within the academy, alongside a rise in antisemitism “disguised as anti-Zionism,” which has ironically resonated among Jews themselves.

Pilon begins by articulating the origins of “the liberal idea in America”—embodying the principles of individual rights, the rule of law, and government by consent of the governed. She sets out a case for its harmony with the moral and political teaching of the Hebrew Bible, as attested by the extensive references to that work by American colonists and those who led the American Revolution.

While Pilon’s general argument is plausible, one must note, she underestimates the philosophical novelty of the specifically modern liberal tradition originating in the teaching of John Locke, whose influence is clearly seen in the Declaration. She goes so far as to suggest that the “honor” of inventing liberalism might rather belong to Roger Williams because of his espousal of broad religious toleration than to Locke. In doing so, Pilon ignores the comprehensive character of Locke’s revolution in political philosophy, of which religious tolerance was but a single element. It was Locke who articulated such liberal principles as the doctrine of self-ownership, the right to unlimited economic acquisition by lawful means, the separation of powers, and the right and duty of anticipatory resistance against incipient tyranny.

Addressing the issue of slavery in the early republic, Pilon properly emphasizes that despite the impossibility of authorizing emancipation in the Constitution (which would have prevented its ratification by the southern states) the Founders laid the groundwork for abolition by refusing to authorize that “peculiar institution”—having already indicated its illegitimacy in the opening paragraph of the Declaration. Hence, they justified Frederick Douglass’s later description of the document not as a foundation for slavery (as intemperate abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison maintained), but as “a glorious liberty document.”

Following the Civil War and the Constitutional amendments that guaranteed equal rights to all inhabitants regardless of race, it is the Southern-born Woodrow Wilson whom Pilon blames for “the hijacking of liberalism” through its reinterpretation as progressivism. She attributes Wilson’s repudiation of natural-rights liberalism to the combination of his education by members of “the disgruntled Confederate intellectual class” at several southern universities; his admiration of the statesmanship of Bismarck and Napoleon, each claiming to represent his nation’s unitary “will”; and the influence of the utilitarian variant of liberalism espoused by John Stuart Mill. In place of a doctrine aimed at securing people’s individual rights, Wilson now portrayed liberalism as a never-ending pursuit through government of a vaguely defined “collective good collectively pursued.” Ultimately, Wilsonian progressivism depended on a Hegelian, organic view of the political community that had first entered American political thinking through its adoption by antebellum Southern apologists for slavery, who of course rejected the notion of equal individual rights.

Following the scholarship of C. Bradley Thompson, Pilon links the triumph of progressivism in American politics with that of historical relativism in the academy and jurisprudence (exemplified by the reputedly liberal, but actually relativist, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., who endorsed the mandatory sterilization of the “unfit” on the ground that “three generations of imbeciles are enough”). Pilon also notes the harmony among the eugenics movement, Wilson’s “Darwinian” approach to politics, and his overt racism. As part of the “semantic reboot of liberalism,” “democracy,” as articulated by Progressive theorists like John Dewey, was pitted against backward “individualism.” This paved the way for the rise of the administrative state, conceived by Progressives as the means by which nonpartisan “experts” would govern under the supervision of elected superiors who claimed to express the popular will. In other words, it was a system resembling the “tutelary despotism,” or nanny state, against which Tocqueville warned.

Pilon notes the link between the progressive movement and the rise of antisemitism. Here politics indeed made strange bedfellows, from the antipathy shared by Southern demagogues and the populist Teddy Roosevelt towards the business success of some Jewish immigrants, to the identification under Wilson’s “Red Scare” of Jews as Bolsheviks (despite his having welcomed the Russian Revolution in the speech announcing America’s entry into the First World War), to the hostility of socialists (many of Jewish descent) influenced by Marx’s virulent Jew-hatred.

Despite the leftist roots of contemporary European antisemitism, most Jews in this country have remained wedded to the progressive Left, reducing their religion (except for the Orthodox) to a universalist ethics, combined with an emphasis on remembering the Holocaust and—at least until recently—support for Israel.

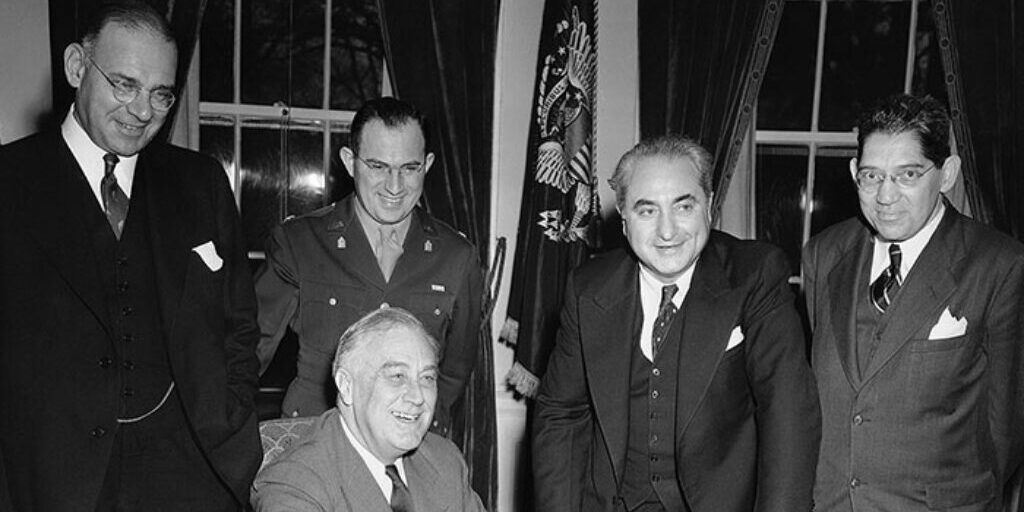

The completion of liberalism’s redefinition as progressivism, as Pilon observes (following legal scholar Ronald Rotunda), was achieved by the master rhetorician Franklin Roosevelt. Starting with his 1932 speech accepting the Democratic Presidential nomination, he wrested the liberal label from Republican champions of individualism like Herbert Hoover, forcing them to accept the less attractive mantle of “conservatism.” By his second term, FDR was even calling opponents to his policies of Constitutionally ungrounded regulation and economic redistribution “fascists.”

Playing into Roosevelt’s hands, the Republican leader and anti-interventionist Robert Taft, only a week before Pearl Harbor, identified those who favored intervention in the Second World War as Wall Street bankers and “fat cats.” This alienated the American Jewish community, already fearful of the Nazi menace, from the Republicans, seeing the reference to fat cats as including their co-religionists—thus driving most Jews into the Democratic party. (Not until 1948 did Taft give up trying to retain the liberal label for limited-government Republicanism.)

Despite FDR’s private antisemitism, he seemed the Jews’ only hope. Only in the 1950s, in Pilon’s account, did a group of Jewish intellectuals, including some ex-Marxists, join in supporting a “new conservatism”—really, an attempted restoration of classical liberalism—centered in William Buckley’s National Review magazine. Curiously, however, Pilon never discusses the neoconservative movement of a couple of decades later, whose leaders included numerous Jewish intellectuals and social scientists like Irving Kristol and Nathan Glazer. They were “neo” in the sense of having accepted the inevitability of something like the Rooseveltian welfare state, but “conservative” in maintaining a commitment to equal rights rather than racial preferences, an “originalist” approach to Constitutional interpretation, and the need for a strong defense and firm resistance to Communist and later Islamist threats from abroad.

Despite the leftist roots of contemporary European antisemitism, most Jews in this country have remained wedded to the progressive Left, reducing their religion (except for the Orthodox) to a universalist ethics, combined with an emphasis on remembering the Holocaust and—at least until recently—support for Israel. Aiming at assimilation, prominent Jews earlier in the twentieth century, like journalist Walter Lippman, financier Bernard Baruch, and Marxian playwright Lillian Hellman, had tried to “obliterate” or obscure their Jewish identity. And even prominent rabbis, notably Stephen Wise, head of the American Jewish Congress, so identified with Franklin Roosevelt as to comply with his dictate that the Jews should “remain quiet” about the Holocaust, even though Roosevelt took no action during the war to order the bombing of Hitler’s death-camp apparatus or offer refuge for Jews who escaped.

Citing Elliott Abrams, head of the Tikvah Foundation, Pilon laments the politicization and secularization of American Judaism in recent decades, such that a large majority of Jews polled in the 1980s cited “social justice” as the most important element of their Jewish “identity,” with religious observance far behind. Pilon next focuses on widespread Jewish acceptance of radicalized, now expressly antiliberal, progressivism in the 1960s, under the leadership of the celebrated Brandeis professor (and escapee from Nazi Germany) Herbert Marcuse. She reminds us of Marcuse’s doctrine of “repressive tolerance,” according to which political speech that opposed the advance of socialism should itself be repressed. Similarly exemplary of the Jewish acceptance of antiliberalism was the fundraiser that composer Leonard Bernstein threw for the violent Black Panthers (memorably portrayed in Tom Wolfe’s essay “Radical Chic”).

Yet as noted by Jewish editor-commentator Norman Podhoretz, in subsequent decades it was no longer necessary for American socialists and statists to shun the liberal label, since the distinction between the two had effectively disappeared. Jewish left-liberals, following the lead of Marcuse protégé Michael Lerner (Hillary Clinton’s spiritual adviser), misused the Hebrew term tikkun olam (literally, “to repair the world”) to signify that authentic Judaism entailed the adoption of socialist policies and of opposition to alleged Zionist excesses committed in defense against Arab atrocities. The self-styled Jewish Voice for Peace reportedly goes so far as to equate the founding of Israel with the Holocaust!

Following a critique of the Obama administration’s policy of “democratic internationalism,” which entailed using force to overthrow the despotic Qaddafi regime in Libya (which posed no threat to American interests) while disregarding aggressive actions by Russia and Syria (which did), Pilon closes with a lament, as “a former inmate of a Communist country,” at “watching the American cultural landscape succumb” to a “groupthink ideology” that threatens its survival. And she quotes the eminent Jewish thinker Ruth Wisse’s appeal to her coreligionists to take to heart their duty as both Jews and Americans to sustain the “greater whole” that ensures their freedom against “the intersectional campaign that is degrading” our country.

By reminding us of the true meaning of liberalism, articulating the reasons for its decay, and explaining how Jews’ particular interest depends on a restoration of something like this country’s founding principles, Pilon’s book constitutes an important contribution to the enterprise to which Wisse calls American Jews and all their fellow citizens of good faith.