Many predicted that tabletop games like Dungeons & Dragons would disappear, but this discounts the power of memory and the need for community.

Losing Gracefully to a Robot

Human beings have invented innumerable games over the centuries, but only the greatest survive across generations. Oliver Roeder‘s Seven Games is a group history that explores some of the best and most enduring games: checkers, chess, Go, backgammon, poker, Scrabble, and bridge. Today we have sophisticated Artificial Intelligence programs that can play these games on a high level, and Roeder discusses these programs in some detail. Nevertheless, this is not primarily a book about machines. By subtitling it “a human history” Roeder emphasizes that the focus is on human players, and the human programmers who have enabled us to enjoy these games on our computers and phones. These games continue to form the basis of our culture.

It is a deeply researched book, and Roeder has approached his subject from all angles: playing the games (both with humans and on computers), immersing himself in the relevant literature, and interviewing those who play, program, and think about these games. The human pathos runs deep throughout: foibles, obsessions, triumphs, and cigarette breaks.

As is fitting for a book with so much to say about the pattern of games, there is a general structure to each chapter. Each of the seven games has its own, in which Roeder begins with an anecdote, either historical or personal. Then he discusses an individual who excelled at playing the game. He then explores the attempt to conquer the game via Artificial Intelligence, especially considering how humans have learned to play differently by learning from the Artificial Intelligence’s gameplay. Finally, he offers some reflections on what the game means for its human players, especially now that computers can beat humans at all of these games.

Game Theory and Artificial Intelligence

While the author has an academic background in Game Theory and Artificial Intelligence, he does not overload the reader with the technical aspects of these fields as they apply to these seven games. He discusses Game Theory and Artificial Intelligence only when germane, which I credit to his being a journalist since he is used to discussing technical concepts that need to be digestible at the breakfast table. Given that I have a similar academic background to Roeder, I would have enjoyed more esoterica.

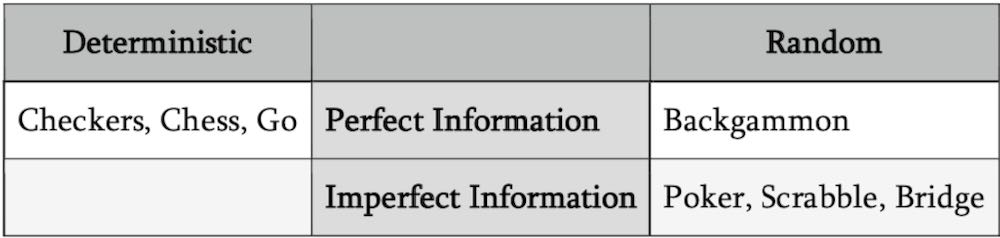

Game theory, in the context of Seven Games, describes board and card games where the outcome of a particular game depends on the strategies of each player. Roeder supplies useful terminology to help readers categorize different games. All seven of the games he features are zero-sum games since a player benefits exclusively at the expense of the other. The first six games in the book are all two-player games, although Scrabble can be played with up to four players, and bridge has four players split into two teams. A game of complete information is when all players have the same information regarding the state of play and so a game of incomplete information is when they do not. Games can either also be deterministic where none of the moves are subject to chance or random where at least some of them are. The goal of Game Theory is to find the strategy that leads to an equilibrium, i.e. the endogenously stable state. The most famous of these is the Nash equilibrium where none of the players would change his own strategy even if he knew the strategies of the others.

Considering Table 1, we can see there is a logical progression from chapter to chapter. As one moves from checkers to chess to Go, these deterministic games of complete information increase in complexity. Backgammon comes next and while it is also a game of complete information, it also introduces chance with its dice. The last three games have both randomness and incomplete information: poker with its cards, Scrabble with its tiles and board, and bridge with its cards and recherché communication system.

Artificial Intelligence is a system that can learn from patterns in the data and create structure, making decisions with minimal human intervention. The initial Artificial Intelligence algorithms were laboriously programmed by carefully replicating human gameplay. This made for some unwieldy code, and the results were often disappointing since the best humans were still better than the machines. But as computing power increased, with the advent of better algorithms, Artificial Intelligence began to best us at our own games.

While an Artificial Intelligence can perform clinching moves in a game that no human has ever thought of, it cannot explain why it chose to do what it did.

Roeder often presents the games as contests of man versus machine, but really, they are man versus machine-programmed-by-man. Of the seven games in the book, two find their natural home in gambling parlors: backgammon and poker. It comes as no surprise that the gamblers were the first to view computers as an ally, and not as the enemy, since money was involved. Of course, people will gamble on all of these games, but backgammon and poker intrinsically incorporate gambling. Given that algorithms have essentially defeated humans at all of these games, players of these seven games now use computer programs to help them play better. Man is now mimicking the machines. Yet, this is not a full-proof strategy. Chess grandmaster Magnus Carlsen learns from the algorithms just as his opponents do. While playing his adversaries, Carlsen purposefully chooses to play a move that a computer would not make. Carlsen’s human strategy confounds his opponent who is wedded to the computer-generated probabilities. Carlsen is the exemplar of a human being more humanlike in response to the advent of the algorithms.

The most riveting chapters are those that feature Roeder playing in high-level tournaments against other humans in the Monster Stack World Series of Poker in Las Vegas and the North American Scrabble Championship in Reno. Computers are present in those chapters, but they are like background actors in a movie who move their lips but don’t make sounds. The main characters are Roeder and his ensemble cast of word freaks and gamblers: a former Scrabble champion, a comedian, a gun-toting Texan woman, an Italian listening to Radiohead, a neo-hippie from San Luis Obispo, et al. Even Roeder’s brief encounter with the Chess Grand Master Carlsen is intriguing even though one knows exactly how the match is going to end.

Games and Leisure

The Scholastics considered understanding to be composed of ratio and intellectus. The former is discursive and logical, enabling us to abstract and draw conclusions. The latter is knowledge from intuition and inspiration. The active reasoning and the passive intellect together form understanding. Josef Pieper described how leisure is the basis of culture, exploring the topic through the Thomistic lens of reasoning born from work, and contemplation springing out of leisure.

Artificial Intelligence, when programmed by some authentically intelligent humans, can perform amazing feats of computation. That is all Artificial Intelligence does, however, while humans can actually think. Artificial Intelligence has a simulacrum of ratio, but it does not even have a facsimile of intellectus. While Grand Masters of Chess or Go may have the impression of an Artificial Intelligence performing an inspired move, there is no real inspiration in play. These moves are based on probabilities, not intuition. Seven Games repeatedly reminds us that while an Artificial Intelligence can perform clinching moves in a game that no human has ever thought of, it cannot explain why it chose to do what it did. Undoubtedly, these feats of calculation are spectacular; we can’t help but describe them as intellectus. The Thomistic schema of understanding is not appropriate for that of machines, and perhaps we need a new vocabulary to explain the kind of intelligence that Artificial Intelligence has. But machines have no motives or elucidations. Despite their great computational ability, computers do not think; they only compute.

For humans, games straddle the divide of ratio and intellectus. To be a serious player of any of these seven games, one must first put in the work to master the rules and strategies. After this, one can rely on intellectus. Roeder discusses an example of this in the chapter on Go. The professional Go player Se-dol Lee played a “divine move” against Google’s DeepMind during their epic battle in 2016, after one of his cigarette breaks. DeepMind had made some impressive moves in Game 2, based on probability. Lee’s Game 4 move was not recognized by DeepMind, since it was based on intuition, not probability. Lee won the game. He was able to defeat of DeepMind because the probability of the move being played was so low that the machine did not know how to respond. Intellectus defeated pseudo-ratio.

Seven Games is an engagingly written and thoroughly researched ode to some of our most beloved games. Roeder empathetically describes the fascinating and often idiosyncratic cast of characters that play and program these games. In his juxtaposition of the personality of humans and the impassiveness of Artificial Intelligence, we perspicuously see the dissimilitude between ratio and intellectus, and Artificial Intelligence’s privation of both. We continue to play games even though we have been bested by machines. This is not out of spite toward the algorithms. Rather, we understand that games are part of what makes culture. Playing games is social, challenging, and fun.

In honor of rapid and blitz chess, here are seven sentences about the seven chapters about the seven games. Checkers is complex and not as simple as it seems, but it should always end in a draw like tic-tac-toe. Chess masters have become even greater as they seek to understand the moves that chess programs make. Go is a beautiful game of grace and tradition that has been annihilated by Artificial Intelligence. The algorithm that was used to solve backgammon is a neural network, which I wrote my master’s thesis about, and this cruelest of games is my personal favorite to play. Human poker is about exploiting those that you are playing, but computer poker is unexploitable and has thus destroyed the essential human element of the game. The greatest English-language Scrabble player of all time won the French Scrabble Championship without knowing French, and the author boringly dwells on the minutia of alphagrams and bingos. Bridge is a point-taking game like spades (which I learned to play at a church retreat in high school) but apart from a handful of rich bridgephiles who sponsor professional teams, the game is dying out. And now that I have caught my breath, let me know if you want to play a game.