Senatorial independence is the highest value, said the Founders—more important than the particular interests of the states from which U.S. senators come.

The Founders’ Religious Liberty, Beyond Rakove

In Beyond Belief, Beyond Conscience, Pulitzer-Prize-winning historian Jack N. Rakove returns to the American Founding, this time to explore the “radical significance” of the free exercise of religion. Rakove sets forth his task as “to explain how the quandaries of Religion Clause doctrine are not merely functions of differences in judicial thinking or ideological commitments, but rather reflect conditions and tensions embodied in our historical experience.” The slim volume elegantly and informatively addresses the historical contexts in which religious freedom emerged in Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries, became a constitutional right in late 18th-century America, and then developed in modern American Supreme Court jurisprudence. Insofar as it sets forth the various historical circumstances that allowed religious freedom to become a constitutional right, it offers a nice introduction to the subject. The book, however, does not quite articulate the Founders’ understanding of religious freedom correctly, which limits the work’s merit as an intellectual history and its usefulness to evaluate contemporary originalist church-state jurisprudence.

“The Nature of Religious Obligation”

Rakove tells a familiar story, but he tells it well. His opening chapters remind us that to “tolerate” another system of belief was not to recognize its equal status, but rather to judge it negatively but also let it persist. “A principled belief in religious freedom as a right to be extended to all was not a value that the [American] colonists gladly packed in the cultural baggage they carried from Britain,” Rakove emphasizes. Political communities in early modern Europe and 17th-century America only became tolerant “because the task of preservation of religious uniformity through tested techniques of persecution had grown too costly.”

At the heart of Rakove’s narrative, which breezily moves across centuries, continents, and key historical figures, is how the emergence of religious pluralism, especially various types of Protestant dissenters, led to religious freedom. The absence of Catholics from British North America “stripped the spiritual landscape of the symbols, practices, and habits that drove European Protestants into militant action.” Puritan orthodoxy encouraged a particularly interior and individualistic understanding of religion. The recruitment of population to Colonial America led to increasing religious pluralism, which in turn made it difficult to say where or in whom orthodoxy resided. Itinerant preachers of the Great Awakening disrupted established religious authorities and multiplied theological perspectives.

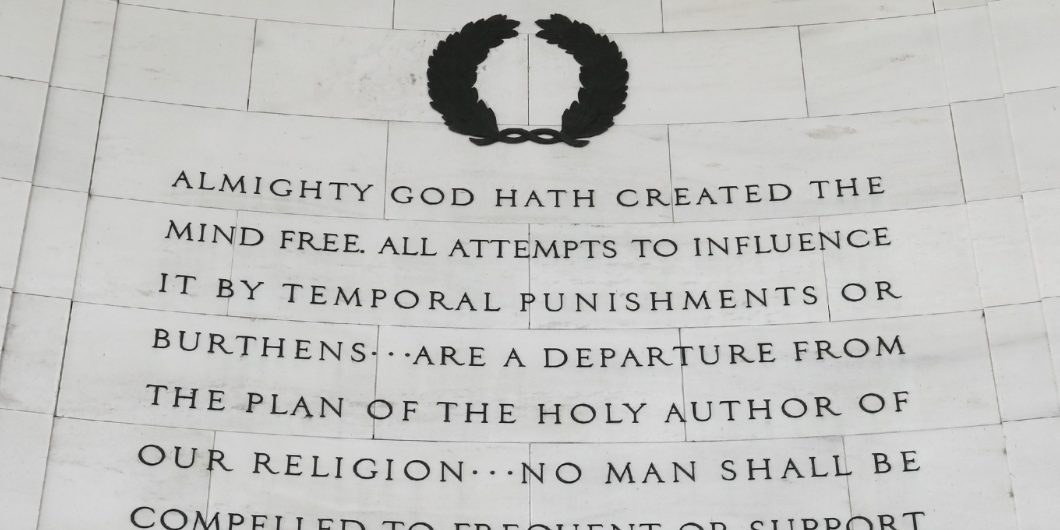

These “factors” made possible Jefferson’s and Madison’s “great project” of religious liberty, which is the book’s central theme. Here Rakove gets two extraordinarily important points exactly right: religious freedom is at the center of liberal constitutionalism and it also occupies a central place in Jefferson’s and Madison’s political thinking. Rakove doesn’t quite get Madison or Jefferson right, however. Specifically, Rakove does not accurately present the Founders’ natural-rights, social-compact constitutionalism and, as a consequence, he somewhat misstates the significance of Jefferson’s and Madison’s legacy.

Let me focus on Rakove’s presentation of Madison. Rakove says he finds the “Memorial and Remonstrance,” Madison’s most philosophical statement on religious freedom, puzzling. In contending that free exercise of religion is an inalienable right, Madison writes:

what is here a right towards men, is a duty towards the Creator. It is the duty of every man to render to the Creator such homage and such only as he believes to be acceptable to him. This duty is precedent, both in order of time and in degree of obligation, to the claims of Civil Society.

Rakove asks, “What can it mean to make religious duties ‘precedent’ in time to one’s civil obligations?” “It is difficult to see . . .” he reasons, “how religious duties somehow preceded civic ones. Any child was always a subject of duly enacted laws before he or she had fashioned a religious identity.” Rakove concludes: “Madison must have had some other conception in mind,” something about “the nature of religious obligation itself.” Rakove is correct that Madison had something else in mind and that it involves the nature of religious obligation. But Rakove never explains it. Madison’s thought seems to have remained an uncompleted puzzle to him.

Everson and its progeny have fostered the idea that religious freedom primarily means freedom from the influence of others’ religious beliefs and practices.

As I have documented elsewhere, the key that unlocks Madison’s “Memorial and Remonstrance” is to read it in light of the Founders’ natural-rights, social-compact constitutionalism. When Madison writes that our obligations to the Creator are “precedent . . . in the order of time . . . to the claims of civil society,” he is not speaking of specific individuals in an actual historical polity, but rather of the social compact theory of government. The Founders held that before individuals form a political community, they are in a “state of nature.” The state of nature lacks a common political authority, but it contains its own obligations nonetheless. To others, individuals in the state of nature have the duty to respect the law of nature and not interfere with their natural rights. To the Creator, individuals owe, in Madison’s words, “such homage and such only as he believes to be acceptable to him.”

This social compact context is crucial to understand the next step in the Memorial’s argument. Madison writes:

[I]f a member of Civil Society, who enters into any subordinate Association, must always do it with a reservation of his duty to the General Authority; much more must every man who becomes a member of any particular Civil Society, do it with a saving of his allegiance to the Universal Sovereign. We maintain therefore that in matters of Religion, no mans right is abridged by the institution of Civil Society and that Religion is wholly exempt from its cognizance.

Madison concludes that the exercise of religion is “wholly exempt” from the state’s cognizance because, when forming the social compact, individuals do not grant government jurisdiction over religious exercises. We withhold this authority from government because the exercise of religion is an inalienable natural right. The duties individuals owe to the Creator—which, again, exist prior to the formation of the social compact—are of higher dignity and authority than any possible political obligations we might subsequently impose on ourselves. And because the nature of our religious obligations is that they must be discharged according to conscientious conviction, we do not and cannot discharge them through state authorities.

Rakove correctly infers that Madison’s and the Founders’ commitment to religious free exercise led them to limit state power, but because he does not follow Madison’s argument carefully, he does not comprehend what specifically this meant. Madison teaches that we do not give government jurisdiction over religious exercises as such. The inalienable character of the right to religious liberty means the state lacks authority to compel, prohibit, or otherwise regulate religious exercises as such. Madison offers a philosophically precise doctrine that specifies exact limitations on state power. All of this flows from the Founders’ natural-rights, social-compact theory of government.

The Naked Public Square

But in Rakove’s account, Madison and the Founders initiated a much more general “movement” for “disestablishment” and the “privatization” of religion. What Rakove says is not untrue—elements of disestablishment and privatization do follow from Madison’s doctrine—but the presentation is significantly lacking in precision.

This lack of precision leads to subsequent errors, omissions, and doubtful conclusions. Rakove repeatedly claims that:

The free exercise of religion treated each member of society, male and female, as morally autonomous individuals who could make fundamental choices that the state had no ability to regulate. Religious freedom was the most liberal right of all, the one that placed the greatest value on the subjective moral independence of individuals.

Rakove never clarifies what he means by “morally autonomous” and “moral independence,” but those phases would not seem to capture the Founders’ position. They did not use the “free exercise of religion” synonymously with “morality.” And the Founders certainly did not believe individuals were “morally autonomous,” especially if that means that every individual is left to determine their own morality. The Founders held morality to be governed by the law of nature, “an eternal and immutable law, which is, indispensably, obligatory upon all mankind, prior to any human institution whatever,” as Alexander Hamilton writes in “The Farmer Refuted.” And as Thomas West has documented in his excellent recent book, The Political Theory of the American Founding, the Founders held that compliance with the natural moral law and the cultivation of moral character (which makes such compliance possible) were legitimate objects of government and subject to prudent legislation. Only religious exercises as such, not morality in general, remained beyond the state’s regulation.

Rakove’s most significant omission relates to how anti-Catholicism shaped modern Establishment Clause jurisprudence, which in turn has affected contemporary notions of religious free exercise. The book is curiously silent on the subject, lacking references to excellent works by Philip Hamburger or Donald Drakeman. A more thorough account would have explored how Justice Black and Rutledge’s dislike of Catholics motivated their “wall of separation” opinions in Everson v. Board of Education (1947). That case and its progeny have fostered the idea that religious freedom primarily means freedom from the influence of others’ religious beliefs and practices. This idea manifests today in those who say Amy Coney Barrett should be ineligible for the Supreme Court on account of being a faithful Catholic. It also is present in a more sophisticated way in scholarship advocating against “third-party harms,” an idea that Rakove endorses at the end of his book. The concept, which lacks much precedential support but nevertheless gained steam as a result of activist scholarship attempting to derail religious liberty exemptions from Obamacare’s “HHS Mandate,” holds that “third parties” should not be impacted on account of other individuals’ religious beliefs and practices. In practice, it means that religious believers should keep their religious beliefs and practices within the confines of their own private homes.

While Rakove all but endorses the “naked public square,” to borrow Richard John Neuhaus’ term, he says that historians in their capacity as historians cannot say which church-state “doctrinal developments are correct [and] which [are] flawed.” Like many of Rakove’s arguments, that is true in one sense and not true in another. It is true that historians are not judges, and it is refreshing to see a bit of academic humility, especially from such a distinguished historian. At the same time, originalist judges contend that they are applying the original meaning of the Constitution. It would seem that those versed in our founding history should be able to render judgment about the historical accuracy of originalist judicial doctrines. With due respect to the difficulties and complications of doing good history, why write a book about the Founders’ understanding of religious liberty if one can’t say who has appropriated that understanding correctly?

Making these judgments would require a precise understanding of the Founders’ political philosophy of religious freedom. Beyond Belief, Beyond Conscience is nicely written and often informative, but it does not offer that depth of understanding. As such, it fails to fully explain the “radical significance” of the Founders’ constitutionalism when it comes to the free exercise of religion.