It is simply too pat to point to bare economic inequality and decry it as necessarily unjust: pursuing equality can often harm growth.

Opulence and Dependency in a Democratic Age

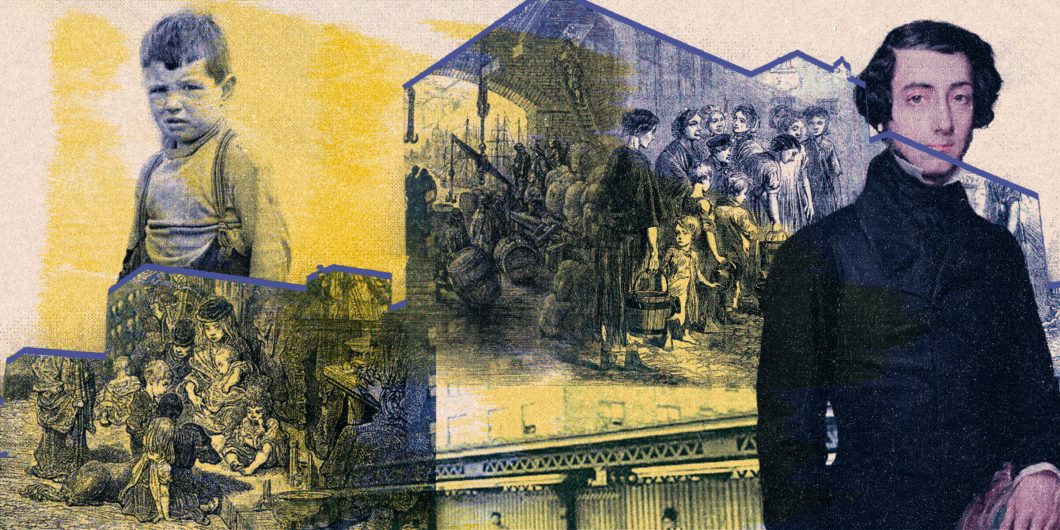

A careful engagement with Christine Dunn Henderson’s welcome new edition of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Memoirs on Pauperism and Other Writings, just released by the University of Notre Dame Press, reveals the multiple ways in which the great French historian, social scientist, and political philosopher remains our contemporary. As in all his writings, Tocqueville addresses the promise and peril inherent in the democratic order emerging throughout what he called “the European/Christian world.” But Tocqueville does so with a constant eye on what endures in human nature and the nature of politics in the new democratic dispensation, and that in relation to what is new and what is to be welcomed and feared.

Democracy is thus an equivocal concept for Tocqueville. It is by no means identical with a regime of political liberty although the America of the 1830s that Tocqueville visited and studied revealed that democratic equality could coexist with the full range of political and personal liberties. The “nature” of democracy—equality, just in itself, giving rise to a troubling and illiberal “passion for equality” —could and must be preserved by a precious “art” of liberty marked by local self-government, the art of association, and a vigorous and independent civil society. That was precisely Tocqueville’s noble project, to ‘save’ liberty and human greatness in the emerging democratic world, to bring together democratic justice and a modicum of aristocratic greatness.

Yet, Tocqueville feared that tyranny in the form of both hard and a uniquely democratic soft despotism was a permanent political possibility under conditions of modernity. He was above all a partisan of liberty and human dignity and not of any particular political regime or social form. There lay his distinctiveness as a political philosopher, statesman, and social scientist. He was neither unduly nostalgic for the glories of the Old Regime nor blind to new threats to the integrity of the human soul that would arise in the democracies of the present and future. He believed in democratic justice, in the palpable truth of our common humanity, of human “similarity,” as he often called it. Even the “most profound geniuses of Greece and Rome, the most comprehensive of ancient minds” failed to appreciate “that all members of the human race are by nature similar and equal.” As Tocqueville observes at the beginning of volume II of Democracy in America, it took Jesus Christ coming down to earth for people to fully understand this truth. At the same time, Tocqueville refused to idolize a “democratic” social and political ethic that was always tempted to say adieu to political greatness and to greatness in the human soul. Such is the spiritual core of Tocqueville’s political science, the central themes and emphases that animate his thought.

The great French political thinker not only provided a remarkably accurate description of “democratic man” but wrestled seriously with the problems and tensions inherent in the emerging democratic political and social order. Political philosophy thus met political sociology in a new and penetrating mix, as is evidenced in the volume under review.

Opulence and Charity

The subtitle of Henderson’s collection is “Poverty, Public Welfare, and Inequality.” We immediately appreciate that Tocqueville’s themes—and conundrums—remain our own. Already in the 1830s, Tocqueville was wrestling with the persistence and even exacerbation of poverty or pauperism in England, the most prosperous and “opulent” nation on earth. His first “Memoir on Pauperism” was delivered to the Royal Academy of Cherbourg in 1835. In that address, Tocqueville noted that much poorer societies such as Spain and Portugal saw comparatively few indigents while an observer such as himself “will discover with an indescribable shock that one-sixth of the inhabitants of this flourishing kingdom [England] live at the expense of public charity.”

In the second part of the 1835 Memoir Tocqueville tells the story quite well. By destroying the monasteries and convents in the 1530s after his break with Rome, Henry VIII suppressed in one fell swoop all of the charitable communities in England. A generation later, confronted by the “offensive sight of the people’s miseries,” Elizabeth I established Poor Laws that provided food and an annual subsidy for those in need. This system persisted well into the 19th century and was in the process of being reformed when Tocqueville and his friend and intellectual collaborator Gustave de Beaumont visited the British Isles in 1833. It had served its purpose of alleviating the worst forms of poverty. At the same time, this “entitlement,” as we would call it today, created new forms of dependency and led to a vast increase in out of wedlock birth since mothers received greater support with each child that entered the world. The contemporaneity of Tocqueville’s discussion is apparent to even the most cursory and ill-informed reader. Tocqueville is speaking of problems to which there are no immediate or obvious solutions and that very much remain our problems.

Tocqueville saw rights as something “grand and virile” that could give rise to a manly and spirited defense of one’s liberty, property, and prerogatives. This connection he draws, here and elsewhere, between aristocratic manliness and democratic rights, sets Tocqueville apart from the more pedestrian modern appeal to natural equal rights. Tocqueville wanted to ennoble “les petits,” giving them a stake in a society of free and responsible citizens and moral agents, rather than “levelling” everyone to the same prostrate condition of democratic mediocrity and powerlessness. The widespread sharing in property ownership was indispensable to that task.

But Tocqueville saw in the right to be provided for by society come what may, a claim to assistance that could enervate and debase human beings rather than “elevating the heart of man.” At the end of part II of the 1835 Memoir on Pauperism, Tocqueville goes so far as to say

that any regularized, permanent, administrative system whose goal is to provide for the needs of the poor will give birth to more miseries than it is able to heal, will deprave the population it wants to aid and console, will over time reduce the rich to being but tenant-farmers of the poor, will dry up the spring of savings, will halt the accumulation of capital, will reduce the growth of commerce, [and] will dull human activity and industry…

This chilling prophecy and warning, however, is not Tocqueville’s final word. It might be said, however, to be his worst fear regarding well-intentioned programs of public charity.

The Necessity of Public Aid

The core of section one of the first Memoir is dedicated to an exposition of the development of human needs and wants from man’s primitive state until the new democratic and industrial age that has reached an apex in parliamentary, commercial, and industrial England. This account is strikingly indebted to a close reading of Rousseau’s Second Discourse, without necessarily sharing Rousseau’s deepest philosophical convictions, especially Rousseau’s open-ended argument for human “perfectibility” or malleability. Tocqueville was far more sober than that. And while Tocqueville fully appreciates the intrinsic connection between “welfare entitlements,” as we now call them, and new forms of dependency and personal degradation, he also knows that personal charity is not sufficient to address the modern problem of pauperism.

The English Poor Laws created dependency and multi-generational pauperism because they abstracted from what Tocqueville saw as an elementary truth about human nature: most human beings have “a natural passion for idleness.” The human desire to “improve living conditions” is less powerful, and less fundamental, than the primordial need to eat and survive. Necessity drives most men to work, so one should not overstate the naturally “entrepreneurial” aspects of the human soul. Those come later (for a minority of human beings) with property to care for, a proper civic and moral education, and the flourishing of an art of association that allows individuals to come together in common enterprises, great and small. Tocqueville would remind those who today call for a Universal Basic Income guaranteed by centralized political authority, or even by supranational institutions, that grave evils can arise from the best of (humanitarian) intentions. Public charity understood as a right to provision from the state, turns out to be something less than the “beautiful idea” with which it is commonly identified. This is a vitally important lesson for this or any time.

The desire for social justice, whatever that exactly means, should not give rise to facile ideological thinking and to utopian misrepresentations of the wellsprings of the human soul.

Still, Tocqueville saw that the development of modern society—and of modern political economy—left industrial workers vulnerable to unemployment and destitution when felt needs for comforts or consumer goods changed, or when the business cycle exposes them to “sudden and incurable evils.” Tocqueville was left with a terrible conundrum: public charity was necessary in any decent society that cares about the least among us, but it also risks giving way to grave evils. In the course of his two Memoirs, and related papers and documents, the French political philosopher and statesman provides no ready-made solution to this problem he describes so well. But he articulates a principled middle path between moral and civic indifference, which is not an option for this essentially Christian soul, and the false charm of a welfare state that creates new “miseries” of its own in the name of a “right” that finally enervates the soul and undermines moral and civic responsibility on the part of the poor and disadvantaged. At the same time, not for once did he think the English Poor Laws should be abolished rather than reformed. Too many vulnerable people would fall through the cracks.

Beautiful Failures

One of the charms of this volume is that we see Tocqueville putting forward a series of tentative proposals and recommendations for working through the conundrum he so lucidly and powerfully exposed in the first 1835 Memoir. He did not reach final or definitive solutions, but prudent and humane suggestions for mitigating agricultural and industrial pauperism, minimizing permanent dependence on the state, while avoiding the libertarian illusion that civil society can adequately address such a pressing and massive problem without significant resort to “public charity.” Tocqueville believed that approach to be utopian in its own way, despite his preference in principle for private over public charity. Tocqueville envisions a place for worker’s associations in the industrial system of the future, the development of large-scale charitable associations to strengthen and go beyond “individual beneficence,” the prospect for opening public schools for the children of the poor, and state-supported “savings banks” for workers, industrial and agricultural. These were and remain thoughtful and creative ideas.

Tocqueville was in many respects a “Christian Democrat,” avant la lettre, trying to conjugate personal freedom and moral responsibility. But he would be appalled by Pope Francis’s suggestion in his recent encyclical Frattelli Tutti that charity become mainly, if not exclusively, a public responsibility. Tocqueville would see the pope’s position as most un-Christian, ignorant in decisive respects of the deepest meaning of the holy charity heralded by the Gospels. In addition, Francis’s seemingly “beautiful idea” is based on ignorance of the tendency of unchecked “public charity” to degrade and enervate human souls. The Church can do better than that and did so in earlier social encyclicals by the likes of Pope Leo XIII and Pope John Paul II. The desire for social justice, whatever that exactly means, should not give rise to facile ideological thinking and to utopian misrepresentations of the wellsprings of the human soul.

Let me end by commending the volume’s editor and translator, Christine Dunn Henderson, for putting together an inspired volume and introducing it in a lucid and informative way. She helpfully highlights the “paradoxes” at the core of Tocqueville’s thoughts on poverty and public welfare: among them, the most opulent country in the world had with the best of intentions institutionalized and aggrandized poverty and pauperism, such that the “beautiful idea” of public charity created miseries all its own.

I dissent about only one point: When Henderson suggests that Tocqueville underemphasizes the “dynamism of a democratic society,” at least in these essays, I think she gives expression to a defect in classical liberal economic reflection. She suggests the poor can “retrain and find new jobs, or invent new products to meet new market demand.” In the long run, and with an ideal “equilibrium,” she is undoubtedly right. But what about now, what about those in immediate need? How does one come to the aid of those in pressing need without creating new “miseries” along the way? This volume does not and cannot solve the problem which will continue to plague democratic societies torn between competing claims based on merit, responsibility, efficiency, and need. But with Tocqueville’s and Henderson’s help, we better see the problem, and can draw on the provisional responses put forward by Tocqueville in a truly thoughtful, suggestive, and humane way.