Owning the Oceans

The fascination with the sea is as old as man. The famous cry—thalatta, thalatta—of Xenophon’s beleaguered 10,000 Greek soldiers (or of what remained of them) upon seeing the familiar waters of the Black Sea after returning from war, showed a loving familiarity with the sea. The Romans embraced the Mediterranean as their own sea—Mare Nostrum—even if they faced it with some trepidation, preferring to have their legions firmly grounded on land. Even if it were “in a fit of absence of mind” (as J. R. Seeley put it in 1883), the British made the wide oceans the great opportunity for becoming a global empire. The Greeks loved it; the Romans profited from it; the Venetians mastered it; then the Atlantic empires extended maritime control over the globe, turning the oceanic routes into arteries of commerce and military force projection that bestowed a power until then unattained by any political entity.

Man’s love story with the sea reaches our own Republic. In the second half of the nineteenth century, after the bloody Civil War and the resulting consolidation of the Union—and then the conquest of the Western frontier—the United States was ready to look upon the oceans not just as protective moats separating it from the world’s travails and the rapacious interests of European powers, but as great highways of trade and opportunity. And it was then that Alfred Thayer Mahan (1840–1914), a US Navy captain and a lecturer at the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island, began to write, gradually building a case for the central importance of the sea for the states’ welfare, and thereby shaping American public opinion. Through the subsequent years, Mahan has assumed the status of a naval demi-god, allegedly responsible for everything from Kaiser Wilhelm’s love for a big navy to a penchant for decisive battles between large fleets, and even for the rise of the United States as a naval power. In all of this, Mahan’s core argument is often lost or misinterpreted.

This is why The Neptune Factor, a new intellectual biography of Mahan by the historian Nicholas Lambert, is a welcome addition to the literature, helping readers to understand not only Mahan but also the role of sea power.

Mahan presents a double challenge for anyone tackling him. First, the sheer quantity of his words is daunting. Once he had set about to write, Mahan wrote copiously. His first book, The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660–1783, was rejected by multiple publishers, perhaps even as many as ten, before finally getting accepted by Little, Brown and Company in 1889. But after this slow beginning, Mahan produced several more tomes, accompanied by a cornucopia of articles and essays, written at least in part to sustain a comfortable lifestyle (this was the blessed period when essay writing was profitable). Quantity did not always mean quality, however, and many of Mahan’s books are more an expression of his own thought process than of finished conclusions. Even chapter one of his first, and perhaps most influential, book, in which Mahan lays out six factors necessary to be a sea power, is a bit meandering and repetitive. It is not the most cogent presentation of an argument.

Lambert argues that there is also a second challenge: Mahan’s interpreters. Some of them have simply failed to understand Mahan’s core argument, primarily making him into an analyst of naval tactics and an advocate of large navies. The great villains in this development were Harold and Margaret Sprout. Present at the creation of the American field of security studies from the early 1940s onward, the Sprouts wrote a book on American naval power. Margaret Sprout then penned an essay on Mahan, published in the first edition of the influential collection of essays, Makers of Strategy, in which she misinterpreted Mahan’s thoughts for the next generations. Calling him the “evangelist of sea power,” she argued that Mahan was first and foremost a navalist, favoring big fleets and decisive naval battles. Mahan for her was essentially a ship guy, whose scholarship was subpar. Sea power, according to this view, was only “a theorem of conflict and combat.”

Nevertheless, for Lambert, Mahan is much more than this dismissive summation. Lambert argues that the core argument that transpires from Mahan’s writings is that sea power, the ability to control maritime routes and prevent others from accessing them, is a tool of political economy, rather than merely military power.

The basic logic is as follows: States need wealth to survive and succeed in the competitive geopolitical environment. “History taught that national power was chiefly a function of sustained wealth generation, broadly defined, and that the single most valuable fount of wealth was overseas trade and its associated commerce.” Because the sea was more efficient at travel and traffic, eclipsing trade by land, it was, in Lambert’s words, the “greatest wealth-generation machine in modern times.” As Mahan wrote in his second book published in 1892, the sea was “the mother of all prosperity” and “the greatest of all sources of renewing vitality.”

It is not farfetched therefore to suggest that Mahan is the theorist of early globalization, founded on sea power.

But the sea brings troubles, along with the benefits. Vying to maintain their access to sea lanes and commerce, great powers compete, even violently, with each other, seeking to guarantee their own supremacy over Neptune’s realm. Contrary to the modern view of international commerce as an agent of peace, Mahan considered it a source of war. The fact that states pursued trade carried “dangerous germs of quarrel, against which it is at least prudent to be prepared.” Writing in the late nineteenth century, Mahan was worried that the United States was unprepared for the reality of increasing global commerce. For decades, they had blithely viewed trade through rose-tinted glasses, not recognizing how much their peace and prosperity depended on the “free security” (C. Vann Woodward’s phrase) provided by oceanic distance and British supremacy.

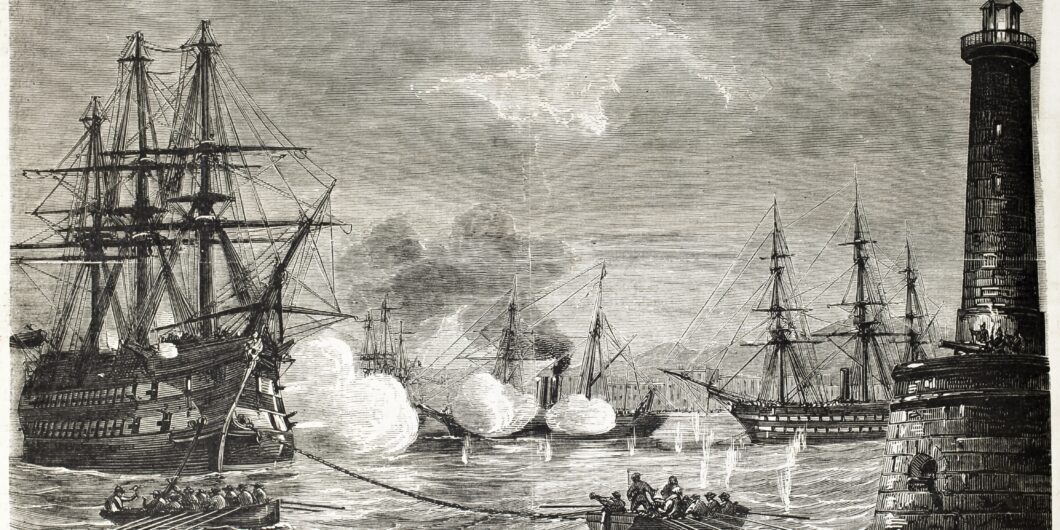

Such competition for commerce and thus for the sea required fleets and resulted in naval battles. There is no sea power without ships. But Mahan considered combat, the kinetic confrontation of ships and fleets, only as the grammar of war. Its logic was political and economic. Another way to put it is that combat—the clash of ships—was part of war, but did not define its character, which was rather economic.

Consequently, in order to be a sea power, it was insufficient to have naval power alone. In addition to a large fleet, it was necessary to have a strong, cohesive government and a persistent participation in international trade. Mahan writes that the “sea power of England … was not merely in the great navy, with which we too commonly and exclusively associate it; France had had such a navy in 1688, and it shriveled away like a leaf in the fire.” Britain also had extensive commercial links, supported by an adventurous national culture, and it was in that “union” of trade and navy, “carefully fostered, that England made the gain of sea power over and beyond all other States.”

Mahan is often contrasted to the British Halford Mackinder, the “apostle of land power” for whom the defining feature of history was the recurrent threat of Scythians disgorging outward from Eurasia’s continental core. Even though he was writing at the peak of British maritime power, Mackinder was wary of the limitations of the sea. In part, his vision was shaped by a focus on ancient history. As Martin Wight has commented, “Mackinder’s most cogent examples of the ultimate superiority of land power are drawn from classical history. Perhaps he did not sufficiently consider that the states-system of classical antiquity grew up round a sea enclosed by land, while the modern states-system has grown up on a continent surrounded by the ocean.”

Lambert’s assessment is more specific: Mahan had a superior understanding of economics. Not only did he understand that maritime transport was cheaper and more efficient, but also, he saw that states could not survive in the long term if they lacked access to markets. The key competition between great powers was less about land and more about access to, and control of, markets and the routes linking them. In the preface to Lambert’s view, James Stavridis, a retired admiral, succinctly sums it up by stating that “sea power [is] the continuation of economics by other means.”

It is not farfetched therefore to suggest that Mahan is the theorist of early globalization, founded on sea power. He “maintained that sea power was an independent force in international affairs—a thing in and of itself—capable of contributing to the power of the state and generating significant political pressure.” In a nutshell, who controls the sea controls the world.

Debates on the role of the sea in politics are never-ending. And Lambert’s book arrives in the midst of another round of the sea power debate in the United States. The central question is an old one: can the United States maintain its position merely by controlling the seas, or does it need ways to project power deep inside the continents? If it’s the latter, is it sufficient to be the preeminent power on the seas, thus holding the keys to global commerce? Mahan, and Lambert with him, seem to suggest that sea power is indeed the determining factor in the great conflicts of modern history and will likely remain so, given the levels of international trade. It is not surprising, therefore, that toward the end of the book, Lambert gently criticizes an influential 1954 essay, “National Policy and the Transoceanic Navy,” by Samuel Huntington. In it, the Harvard professor argued that the role of the navy was to aid the projection of power on land. This had to be the navy’s “strategic concept,” its purpose, in the post-World War II age because the strategy of the United States in Huntington’s words, “involved the projection, or the possible projection in the event of war, of American power into that continental heartland” of Eurasia, where the principal threat, namely the Soviet Union, was located. Lambert thinks that such an argument was driven by an assumption, mistaken as it turns out, that international trade would not increase beyond what it was in the first decade or so after World War II, thus diminishing the importance of sea power to a role supporting operations on land.

But Lambert, and indirectly Mahan, may be giving too little credit to Huntington and his view of sea power. After all, the war in Ukraine—the outcome of which will define the geopolitical dynamics of Europe and much of Eurasia for years—is mostly a land affair, with sea power playing a secondary role. American sea power has little to say here, and even a blockade of Russia would achieve very little. Indeed, like the development of railroads in the nineteenth century that consolidated continental markets, the current strategy of US rivals, such as China and Russia, may be to lower their reliance on the sea and to look upon the Eurasian mass as the center of their commercial interactions.

Undoubtedly, sea routes remain the principal arteries of global trade, the importance of which becomes more visible in the moments when freedom of navigation is threatened. Recent events in the Red Sea have shown what happens when maritime navigation is interrupted. Houthi rebels are attacking commercial vessels resulting in a diversion of trade away from the Suez Canal (adding more than 3,000 nautical miles and 8-10 days), which is increasing prices of shipped goods. This has truly global effects. But it is also true that some states are not as dependent on the sea as Mahan seems to assume, rendering the realm of Neptune less critical to their economic survival. Controlling the oceans will not have the same significance in the future as in the past. The Columbian epoch is, after all, not eternal.