The Biological Sociology of the Good Society

In 1975, the publication of Edward O. Wilson’s book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis provoked a debate over his proposed biological explanation of the social behavior of all animals, including human beings. He was attacked by both left-wing thinkers (like Stephen Jay Gould and Richard Lewontin) and right-wing thinkers (like Roger Scruton and Wendell Berry) for promoting some undesirable “isms”: reductionism, determinism, essentialism, and social Darwinism. He was also criticized for spinning out “just-so stories”—fanciful narratives for explaining social behaviors as evolutionary adaptations that are untestable and thus unscientific. It was also claimed that Wilson’s biological explanation of human morality committed the naturalistic fallacy by moving illogically from a scientific explanation of the natural facts of how human beings behave to an ethical judgment of the moral values of how they ought to behave.

We can now look back over 45 years of theoretical and empirical research studying the biology of social behavior along the lines suggested by Wilson, although most of that research has sailed not under the flag of “sociobiology,” but under flags like “evolutionary psychology,” “human behavioral ecology,” “gene-culture coevolution,” “social neuroscience,” “biopolitics,” and “evolutionary multilevel selection theory.” In recent years, we have seen a half dozen or more books surveying, synthesizing, and defending that research.

One of the best of those books is Nicholas Christakis’ Blueprint: The Evolutionary Origins of a Good Society. Christakis is a physician and sociologist who teaches at Yale University. He advocates a biological sociology of the good society. That is remarkable because most sociologists have scorned any biological explanation of human sociality and insist that human social order arises as a purely cultural invention imposed on a human blank slate.

Although Christakis says little directly about E. O. Wilson, Blueprint can be read as showing how the criticisms of Wilson’s sociobiology can be answered through three lines of argumentation. The first argument is that a biosocial research program can generate testable predictions that cannot be derided as just-so stories.

The second argument is that this research program requires three levels of analysis—the genetic history of the species, the cultural history of groups, and the individual history of agents in the groups. This complex multileveled analysis cannot be dismissed as reductionism, determinism, essentialism, or social Darwinism.

The third argument is that there is nothing fallacious about a biological science of the natural goodness of society. A biological sociology can judge a society as naturally good if it conforms to what Christakis calls the “social suite” of evolved human nature. And although he does not explicitly say so, Christakis’ reasoning suggests that Friedrich Hayek was right about there being a convergent evolution towards the free society as the best society.

Testing the Social Suite

Like Wilson, Christakis claims that the capacity to make societies is a biological feature of the human species, just like any of the other biological traits that are necessary for our species to survive and reproduce. This innate capacity depends on a social suite of eight natural desires expressed in some form in every human society:

- The capacity to have and recognize individual identity

- Love for partners and offspring

- Friendship

- Social networks

- Cooperation

- Preference for one’s own group (that is, “in-group bias”)

- Mild hierarchy (that is, relative egalitarianism)

- Social learning and teaching

To prove the reality of this social suite, Christakis generates ten kinds of testable predictions. The first prediction is that nonhuman animals who have evolved to be naturally social should display some, if not all, of the traits in the social suite. For example, prairie voles are naturally bonded to their sexual partners and their offspring, and this bonding is facilitated by neurotransmitters (oxytocin and vasopressin) that seem to work in similar ways for human beings.

Second, one can predict that when people are accidentally thrown together into communities, one should see the social suite emerge in those communities that are successful. To test this prediction, Christakis surveys the history of people stranded in isolated spots after shipwrecks.

Third, when people form utopian communities—like the Shakers in America or the kibbutzim in Israel—Christakis predicts that those that deny the instincts of the social suite (such as the bond of parents to their children) will fail. The history of such intentional communities seems to confirm this.

Biologists studying social animals over the past 45 years have seen that the social life of nonhuman animals is shaped by their cultural history and their individual personalities, just like human societies.

Fourth, one can set up artificial communities to see if they spontaneously show the emergence of the social suite. Christakis has recruited people through online crowdsourcing platforms (like Amazon Mechanical Turk) to participate in online experiments in which people form social networks, with Christakis manipulating the structure and rules of social interaction. He has found that people prefer to be friends with nice, cooperative people and to break their ties with mean, cheating people. Furthermore, studies of how people play online games show that their social interactions online resemble their interactions in the real world, which conform to the features of the social suite.

A fifth kind of prediction is that the traits of the social suite should be manifested as cultural universals. So that, for example, ethnographic surveys of hundreds of cultures around the world should show that all, or almost all, of them show some idea or practice of friendship.

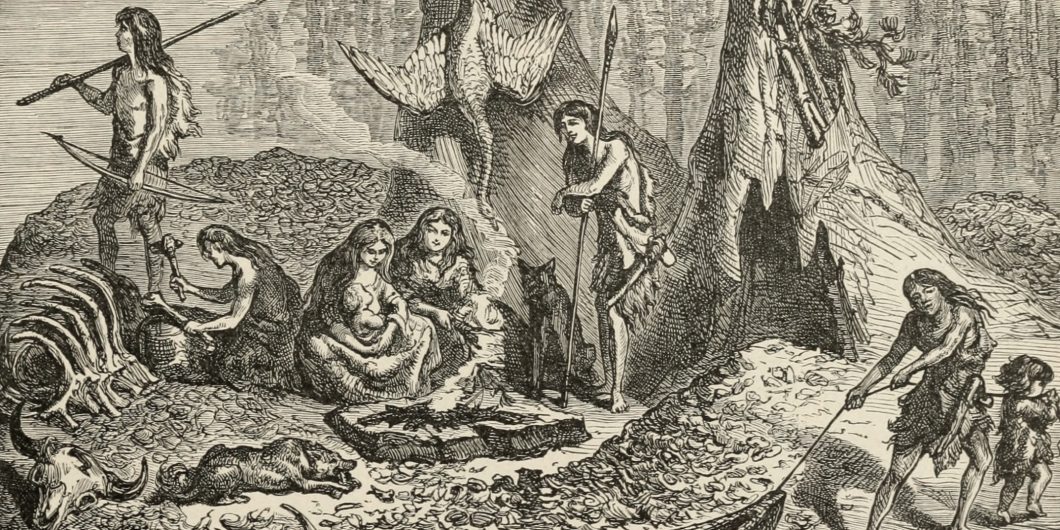

A sixth kind of prediction is that if the human social suite first evolved among our prehistoric hunting-gathering ancestors, then studies of those foraging bands that still exist today should exhibit that social suite. Christakis and his colleagues have studied the Hadza, an ancient nomadic foraging people in Tanzania, and their social life shows the eight traits of the social suite. They are not an exact proxy for our prehistoric ancestors, because the Hadza have been in contact with modern people—including anthropologists—for a long time. But still, they are probably similar to the first human societies.

Seventh, there should be some genetic propensities to the social suite. For example, some researchers have shown that the pair-bonding of prairie voles is associated with the expression of a single gene; and there is some evidence that a similar gene is associated with human pair-bonding.

Eighth, Christakis can predict that the social instincts of evolved human nature will be expressed early in infants and children. And, indeed, in experiments with babies as young as three months, researchers have shown that young children have a rudimentary moral sense that supports social behavior. For example, when they are shown a puppet show, they prefer the puppets that help other puppets, and they want to punish the bad puppets that harm others.

A ninth kind of prediction is that when people around the world play experimental economic games, they will tend to cooperate with those who are themselves cooperative, and they will punish those who are not cooperative. This prediction has generally been confirmed, although there is some variation across cultures depending upon variations in social experience.

A final kind of prediction made by Christakis is that each of the propensities in the social suite should be enabled by neurophysiological mechanisms. So, for example, if there really is a capacity to have and recognize individual identity, then we should expect to find that the brain has the ability to perceive one’s own individual identity and to recognize the identity of other individuals. And, in fact, recognizing faces is a crucial part of social interaction. Humans with a brain disorder that impedes the recognition of faces—prosopagnosia—are severely handicapped in their social interactions. Moreover, human faces differ one from another in ways that make each face uniquely distinctive. Humans and some other animals also recognize their own individual identity as shown by recognizing their own faces in a mirror.

Whether the evidence surveyed by Christakis truly confirms these ten kinds of predictions is open to debate. But still, he can insist that these are in principle testable predictions from his biological theory of social behavior. Consequently, his theory cannot be easily scorned as a collection of unprovable just-so stories.

Three Levels of Biological Social History

Every species of social animal has a distinctive genetic blueprint that sets the general patterns of social behavior found in every group. But this genetic blueprint is not deterministic, Christakis observes, because it allows for cultural variation among different groups of animals and individual variation among the animals in each group. Consequently, a biological sociology must move through three levels of animal social life—genetic history, cultural history, and individual history.

A book by sociologist Kenneth Bock—Human Nature and History—was one of the first critiques of Wilson’s Sociobiology. Bock argued that the biological study of animal nature cannot explain human history, because “animals other than man do not have histories,” and human history in its contingency and diversity shows a human freedom from nature that transcends human biology. Human history can be studied by historians, but not by biologists.

“The universals of the social suite—shaped by natural selection and encoded in our genes—are not only facts, but also sources of our happiness.”

Nicholas Christakis, Blueprint

On the contrary, as Christakis indicates, biologists studying social animals over the past 45 years have seen that the social life of nonhuman animals is shaped by their cultural history and their individual personalities, just like human societies. For example, Jane Goodall has found that while the chimpanzees in the Gombe Stream National Park in Tanzania showed some general patterns of social behavior that were the same for other chimpanzee groups in Africa, the chimpanzees of Gombe had a socially learned suite of cultural traditions that distinguished this chimpanzee group from other groups in Africa with different social traditions. Goodall has contributed to a growing body of biological research on cultural learning and teaching among many species of social animals. Human beings are not the only animals who have a cultural history.

Goodall has also contributed to the biological study of animal personalities, because she found that each of the individual chimpanzees at Gombe had a personal identity and that the history at Gombe was shaped by the social interaction of these unique individuals. One of the most extensively studied models of human personality is the “Five Factor Model” that describes human personality differences across five domains—Openness to Experience, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism (OCEAN). Each domain corresponds to an axis running from high to low. This same OCEAN model can be applied to the study of nonhuman animals. And it has been shown that chimpanzee personalities display all five domains, just like human beings.

Far from requiring a genetic reductionism and determinism, Christakis’ biological sociology must study the emergent coevolutionary history of genes, cultures, and individuals. The genetic history enables and constrains, but does not determine, the cultural history. The genetic history and the cultural history, in turn, jointly enable and constrain, but do not determine, the individual history.

The Convergent Evolution of a Naturally Good Society

The ethical naturalism of Christakis’ biological science of a good society can be criticized as a fallacious derivation of moral values from natural facts. But he answers this criticism by appealing to the idea of “natural goodness” as developed by philosopher Philippa Foot. Foot argued that the moral evaluation of human actions has the same logical structure as the natural evaluation of other living beings. Unlike the non-living world, plants and animals show an immanent teleological structure in the nature of each species. We can then judge an individual plant or animal as to how well it fulfills its natural end. So, for example, we can judge the roots of an oak tree as good if they effectively draw water and nutrients from the soil and support the weight of the tree. By contrast, we can’t make a similar evaluation of the rustling of the tree’s leaves in the wind, because we don’t see this as contributing to any natural need of the tree. Similarly, we might judge social mammals by how well the mothers nurture and train their offspring to fulfill their needs as social animals. Thus, our evaluations of plants and animals can be grounded in natural facts about their species, which we learn by studying their natural biological history.

We can say then that human morality consists of hypothetical imperatives constrained by our biological nature as social mammals. Considering the nature of the human species, human beings have certain universal social desires—the social suite—that set the generic ends of human life, and so we can judge the goodness of a society by how well it promotes the satisfaction of those ends, which constitutes human happiness or flourishing.

An obvious objection to deriving moral norms from nature in this way is that it deprives us of any morally binding rules, or what Kantian philosophers call categorical imperatives. We can say that a tree has defective roots, but we do not say that the tree is morally bound to have good roots. Don’t we need some binding imperative to explain human moral conduct? Christakis does not mention, much less answer, this objection.

One response to this objection is to say that if the good is the desirable, then a binding categorical imperative must depend upon a hypothetical imperative about our desires. If we are told that we ought or ought not to do something, we can always ask, Why? And ultimately the only final answer to that question of motivation is that obeying this ought is what we most desire to do if we are rational and sufficiently informed about our natural human desires and the necessary circumstances for satisfying those desires.

So, for example, if we are told that we ought to be faithful to our friends, we can understand this as based on a hypothetical imperative: if you desire the love of friends, you ought to cultivate personal relationships based on mutual respect, affection, and shared interests. We can then recognize a good society as one that enables friendship and all the other natural desires of the social suite.

Christakis sees a convergent genetic evolution towards this good society: many different mammalian species have independently arrived at similar solutions to the challenge of living in groups, such that the behavioral traits of the human social suite appear in some form in many other species. This resembles Hayek’s claim that human history shows a convergent cultural evolution towards the free society, because such a society—with institutional rules protecting private property, free trade, and contracts—is efficiently adaptive in promoting productive cooperation.

Christakis writes: “The universals of the social suite—shaped by natural selection and encoded in our genes—are not only facts, but also sources of our happiness. They are essential to the ability to judge which social arrangements are good for humans.” The free society thus cultivates human happiness. We might find empirical evidence for this link between happiness and certain social arrangements by looking at some global social surveys—such as the Human Freedom Index and the World Happiness Report—and noticing that the liberal regimes tend to be high in both freedom and happiness, and the illiberal regimes tend to be low. The Hayekian could argue that by this standard we can judge the free society to be the best society, because it most fully satisfies the social suite of our evolved human nature, and because individual freedom is required for having and recognizing the individual identity that is foundational for the social suite.