Why not consider the crafts and trades of vocational training, the performing arts, or the service professions part of the liberal arts?

The Civic Responsibilities of Liberal Education

The death of liberal education, like that of Mark Twain, has been greatly exaggerated. In the past few years, there have been several books defending liberal education, whether because we need to rediscover our inner life, examine what it means to be human, or make our students reasonable people. Continuing this conversation is Justin Buckley Dyer’s and Constantine Christos Vassiliou’s new edited collection, Liberal Education and Citizenship in a Free Society.

As an education befitting a free person, liberal education not only teaches students what to think, but how to think. This in turn requires universities to promote open inquiry, reasoned debate, civil discussion, and a commitment to freedom of speech and thought. For Dyer and Vassiliou, the conditions of such an education create a space for contemplation and leisure that permits “students to reflect upon what it means to live nobly before assuming their place as custodians of a free society.”

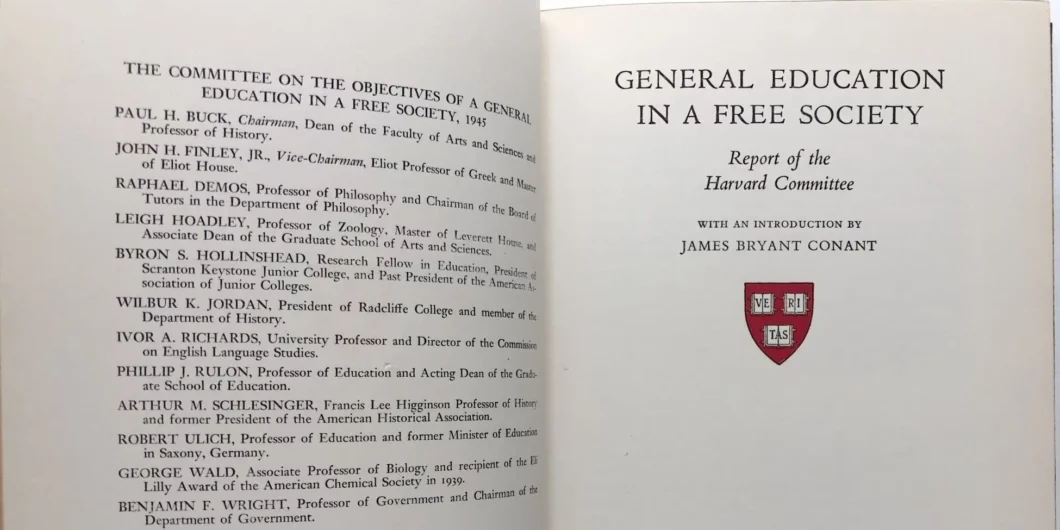

In the Middle Ages, liberal education was taught as the Trivium and Quadrivium; in modern America, they have been transformed into general education. Yet both aim to make people free. Harvard’s 1945 report, General Education in a Free Society, best articulated this aspiration: “If one cling[s] to the root meaning of liberal as that which befits or helps make free men, then general and liberal education have identical goals.” “The task of modern democracy,” Harvard’s report proclaimed, “is to preserve the ancient ideal of liberal education and to extend it as far as possible to all members of the community.”

Needless to say, the modern American university has not realized this vision with its problems of administrative bloat and ideological conformity. Still, there are some, like Dyer and Vassiliou, who are calling for a renewal of liberal and general education as “a distinctively American civic education focused on US history, institutions, and culture.” This volume is part of this endeavor to preserve liberal and civic education—an education in and for freedom—in light of “the unique market, technological, and intellectual challenges faced by advocates of liberal education” today.

Liberal and Civic Education

The first question to be asked of the contributors is whether liberal and civic education are compatible. The aim of liberal education is to make one free from utilitarian concerns; the aim of civic education is to cultivate good citizenship in students. According to Plato and Aristotle, these two poles of human life—the pursuit of leisure and of political ends—not only define our education but our very human existence. The demands of the political community to which we belong are not easily reconcilable with the idea of liberal education. Think of the scientists in Oppenheimer who later became horrified when their invention of the atomic bomb was used for the political goal of ending the war with Japan. The tension between these two types of education is great.

The first set of contributors argue that liberal and civic education are mutually exclusive. These authors are preoccupied with returning liberal education to its original purpose of studying subjects for their own sake and suggest strategies to navigate the dangers of postmodernism, cancel culture, and ideological pedagogy. For instance, Anna Marisa Schön calls for reading Christine de Pizan not as a “proto-feminist” but as someone whose philosophy transcended the narrow perspective afforded by her gender. Clifford Orwin, Lindsay Mahon Rathnam, and Lincoln E. F. Rathnam endorse the inclusion of non-Western thinkers in the framework of liberal education. Through the lens of liberal education, non-Western thinkers like Confucius could be understood as espousing universal views about the human condition rather than being representative of a particular ethnic study.

Alin Fumurescu advocates for a “pedagogical shaming” modeled after Socrates and Diogenes the Cynic. These philosophers employed shame to educate the democratic souls to cure them of their ignorance and foolishness, as opposed to today’s use that coerces people to subscribe to the latest ideological fads, e.g., fat-shaming, age-shaming, slut-shaming. Complementing Fumurescu’s chapter is Lorraine Smith Pangle’s, which looks to Aristotle’s virtue of phroneis as well as the virtues of intellectual openness, curiosity, civility, and honesty to renew liberal education. These virtues, along with the inclusion of non-Western works grounded in liberal education, present a commonsensical and pragmatic approach to making liberal education relevant in a multi-ethnic society like the United States.

However, these authors elide the question about the relationship between liberal and civic education, believing they are distinct and separate realms of human formation. It is only in the last chapter of this section that the issue is directly addressed. In his study of Plato’s Republic, Dustin Gish argues that liberal education prepares students for the political life, as demonstrated when Socrates attempts to reform his interlocutors’ souls so they can become just rulers of the polis. According to Gish, the curriculum of the philosopher-king is revealed to be a true liberal education which in turn establishes the foundation of civic education in the practice of justice.

But is this connection between liberal and civic education as tight and sequential as Gish claims? Or is this relationship non-existent as the previous contributors imply? Let me suggest a third option: liberal and civic education are related to one another but exist in a state of tension that is both necessary and beneficial. Civic education does not possess a monopoly over excellence or knowledge. It therefore must recognize standards of excellence and sources of knowledge that exist outside of it—and should learn from them—to improve the civic health of the state. For example, this country at one time codified segregation, but when civil rights leaders looked outside the state for the principle that all citizens should be afforded equal rights, they then persuaded their fellow citizens of this and forged a better regime.

The contributors in Liberal Education and Citizenship in a Free Society demonstrate why liberal education is central to liberty but disagree with one another about whether it is central to civic education.

The Classroom

But how does one teach liberal and civic education, especially in a campus culture that is litigious and technologically driven? Sarah Rich-Zendel deals with the first question; Carson Holloway and Steven McGuire with the second. Zendel asks whether the university can mitigate the harm of sexual misconduct to women without relying on a punitive administrative structure that forecloses the opportunity for them to enjoy pleasure and desire that facilitates a liberal education. While she invokes Freud, one is also reminded of Plato’s Symposium where eros is capable of inspiring virtue and contemplation of the highest things. The taming of eros under the university’s Title IX policies appears to be a triumph of civic over liberal education, and perhaps a much-needed one. But at what cost? The question remains whether the university can cultivate eros in its students without the potential harm, like sexual harassment, it could bring.

Both Holloway and McGuire examine the incorporation of online technology in the classroom as forced upon faculty by the university during the COVID-19 pandemic. They conclude that the modern university is both Baconian in its desire for new insights and power and Socratic in the preservation and transmission of ancient wisdom. For these contributors, both are educational goods, but liberal education is the higher one. They point out that online education is a meditated instruction that fails to capture the in-person social interaction between teachers and students that Aristotle believed was requisite for liberal education.

Whereas Holloway and McGuire believe that online education is not compatible with liberal education, one wonders whether something like Zoom is suitable for civic education. To me, it would seem the answer would be yes. Civic knowledge—the fundamental understanding of the structure and function of one’s government, one’s civic rights, and one’s civic responsibilities—could be conveyed to students online just as effectively as in the classroom since this type of education is not as open-ended in its inquiry as liberal education. And civic action—students participate in civic engagement whether in political or nonpolitical action—can be conducted as successfully online as in person, whether it is emailing your representative or organizing a virtual community to protest. As technology becomes more and more part of university life, there may be some forms of education, like civic education, that will benefit, and others, such as liberal education, that will have to find new ways to ensure its survival.

The University

Advocates of liberal education also must persuade administrators and staff about its importance, particularly during a time when pre-professional schools are in ascendancy. Steven Frankel, Donald Drakeman, and Kendall Hack present innovative arguments that liberal education should be required in these schools because of the value it brings to pre-professional students. For Drakeman and Hack, having liberal education courses embedded in MBA programs offers valuable insights to students about the political and social environment in which their businesses will operate. With a liberal education, MBA students will understand their place within the broader community which will contribute to their career success. Frankel supports Drakeman’s and Hack’s proposal by citing both Tocqueville and Alan Bloom about professional schools’ need for liberal education to avoid a truncated or abstracted account of human nature. But, unlike Drakeman and Hack, Frankel believes that liberal education helps students see the relation between their professional aspirations and their citizenship, directly linking liberal and civic education as a necessary good for a commercial democracy to sustain itself.

One of the contemporary challenges to liberal education is the erosion of academic freedom in American higher education. While critical race theory and other ideologies have attacked academic freedom, Lee Ward believes this is merely a manifestation of the more fundamental problem in the university: the weakening of the principles of collegial governance and the system of tenure. The introduction and employment of academic program reviews by administrators have led to the restructuring of programs in the humanities and social sciences in favor of pre-professional programs and a decrease in the number of tenured and tenure-track faculty. The result is that those programs most invested in liberal education have been reduced, and fewer faculty are willing to exercise their academic freedom because fewer enjoy the protection of tenure. For Ward, neither liberal nor civic education can survive until the university returns to a form of faculty governance. However, one wonders whether this would be merely letting the inmates run the asylum with the ideological lopsidedness of faculty.

Both José Daniel Parra and Gregory A. McBrayer propose the study of the great books to revitalize liberal education. Both authors subscribe to Leo Strauss’ argument that the study of great books remedies the deficiency of the modern condition that seeks comfort instead of excellence. Students should neither be apolitical (the default position of pre-professional schools) nor political ideologues (as is the case of the humanities and social studies). Instead, a culture of moderate expectations of politics should be cultivated so it is neither banished nor all-encompassing in the curriculum. Such an expectation would give space to those who wish to be liberally educated in studying the great books.

To revitalize civics education, George Thomas looks to the teaching of constitutional law. With less than half of US adults (47%) able to name all three branches of government, there is a crisis in civic education in this country. According to Thomas, this is not surprising since none of the top schools have a required course in American government, thought, history, literature, or culture. And even if they did, how would these subjects be taught—as one of repudiation or celebration? By teaching constitutional law, Thomas believes that students will acquire basic civic knowledge about the US Constitution and more, for the understanding of the US Constitution requires knowledge about American history and the political principles that underlie that history. With this grounding in constitutional law, students have a common reference point to discuss and disagree with one another about the American regime instead of reciting the latest propaganda they read on social media. As Thomas notes, for those who want to criticize the country, it is important to know one’s country first.

The contributors in Liberal Education and Citizenship in a Free Society demonstrate why liberal education is central to liberty but disagree with one another about whether it is central to civic education. Of course, the question about the relationship between liberal and civic education has been an enduring one since the time of the Greeks and will continue to be with us forever in the future. The authors in this volume have approached this question in a variety of ways from classroom teaching to the university administration to the philosophical discussion, with each adding insight into this discussion about liberal and civic education. Reading it may not provide you the answers you are seeking but it certainly will raise more questions for you to think about—just as any good liberal or civic education should.