The Claims of Conscience

No review—even a longish review such as Law and Liberty allows—can do justice to this book, The Disintegrating Conscience and the Decline of Modernity. It is the most recent in a distinguished line of writings by Steven D. Smith, all focusing on issues of religion and the law. But this is no survey of legal doctrine on the First Amendment’s religion clauses. It is a story in three substantive chapters of three thinkers and their grappling with the question of conscience. The three—Thomas More, James Madison, and William Brennan—in turn, represent three moments, or distinct conceptions of conscience, not merely as they apply to the law but in itself and as they relate to the broadest themes of their respective historical settings. As told by Smith, it is a tale of “the decline of modernity” producing the “disintegrating conscience.” Or is it? It is also the tale of the “self-disintegrating conscience” as revealed in successive revelations of the inner nature (and weakness?) of conscience as provoked by different historical configurations.

On one side, Smith seems to be joining the “blame modernity” crowd; on the other, he seems to be absolving modernity of all blame, even seemingly to support the idea that responsibility for modernity and many of its ills lies in the degenerative dynamic of conscience itself. Many readers may find this ambiguity unsatisfactory or even disturbing, but in my opinion, it reflects the depth of insight and the intellectual probity of the author. And it helps make the book as provocative and interesting as it is.

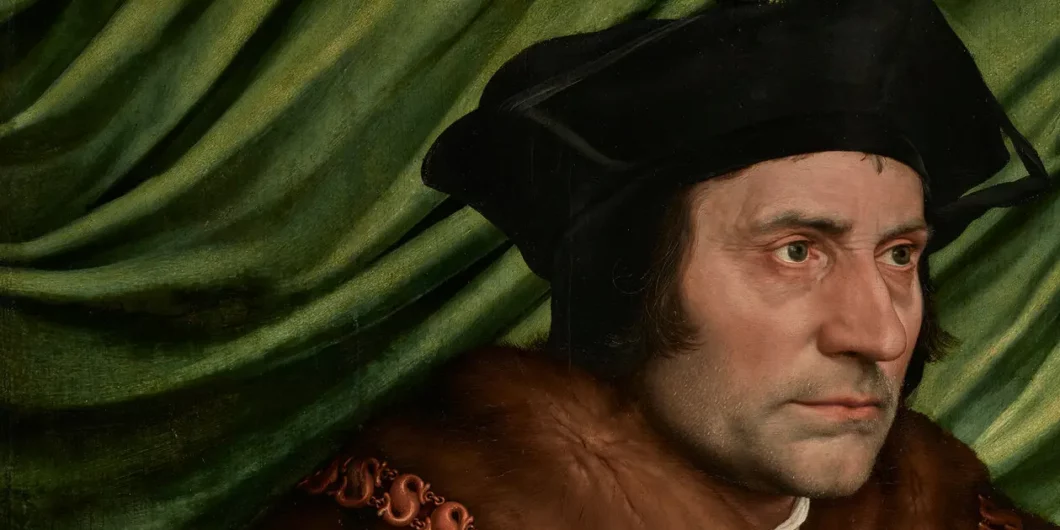

Smith presents More in the old-fashioned way, as a martyr for conscience, rather than in the new-fangled Hilary Mantel manner as a hypocrite of conscience. That is not to say that Smith ignores the various apparent inconsistencies in More’s thoughts and actions that Mantel and other denigrators of More notice—above all, his claim that he takes the stand that he does on King Henry’s divorce on the basis of claims of conscience he believes should be recognized and honored, while at nearly the same time hunting down and advocating the severe punishment of Protestants who break with the Church on the basis of claims of conscience. The explanation for More that Smith offers is really the orthodox view that conscience needs to undergo “formation” before it can claim the kind of authority More attributes to it. That formation shapes conscience to recognize and accept the “collective understanding of Christendom” as its basis. This saves him from the charge of inconsistency and hypocrisy. But, as Smith points out, this kind of formation “is a possibility only if there is a united Christianity to which you can look in shaping your beliefs and actions.” Operating on such an understanding, More finds authority for conscience and its claims in the will of God as expressed in Christendom, which thus prevents the claims of conscience from decaying into “everyone doing what (seems) right in his own eyes.” The reliance on this “collective understanding” thus prevents the reliance on conscience from being dissociative of social orders and keeps the focus of the claimant to the rights of conscience on the truth of the substance of the claim.

James Madison, father of the Constitution, but more importantly in this context, the author of A Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments, a petition drawn up in protest of a law proposed by Patrick Henry to, in effect, tax the citizens of Virginia to pay the salaries of ministers. This law differed from the old religious establishment in that each taxpayer must designate which church or sect would receive support from his tax. It was, in this regard, a recognition of the pluralism of Virginia Christianity in the eighteenth century. Madison resisted this law, partly on the basis of Article 16 of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, which provided for “the free exercise of religion, according to the dictates of conscience.” That phrase about “free exercise of religion” happened to be inserted into Article 16 at the behest of none other than James Madison himself, in an amendment to an earlier draft of that Article which had provided instead for “the fullest toleration in the exercise of religion, according to the dictates of conscience.” Madison apparently understood the provision for “free exercise” to forbid Henry’s tax proposal.

In an extremely complex and subtle analysis, Smith maintains that Madison’s opposition to the tax rests on a major modification of the understanding of conscience as evoked by More. The juxtaposition of “free exercise of religion” and “according to the dictates of conscience” both changes and carries forward elements of More’s view. On the continuity side, Madison reiterates, perhaps even extends the claim of conscience. He also maintains the grounding of the claim of conscience in the divine. His Memorial and Remonstrance opens with an appeal to “Religion or the duty which we owe to our Creator” as the foundation for the assertion that “the Religion … of every man must be left to the conviction and conscience of every man.”

Despite these important continuities, Smith pronounces Madison’s notion of conscience to be very different from More’s. Gone is the notion of formation, or rather of formation according to the consensus within Christendom, in part, because by Madison’s time there was no consensus within Christendom. As Madison formulates the duties we owe to the Creator: “It is the duty of every man to render to the Creator such homage and such only as he believes to be acceptable to him.” The individual’s own judgment, not the “collective understanding of all Christians” sets the standard for the right conscience and its rights. As Smith neatly puts it: “Both More and Madison could affirm: ‘I must do what (I believe) God wants me to do.’ But the emphasis is subtly shifting, from an accent on ‘God’ to an accent on the ‘I’. ‘I must do what (I believe) God wants me to do’ is becoming ‘I must do what I believe (God wants me to.).” Madison, says Smith, no longer accepted the established Church of England, but he, in effect, “moved to establish … his own religion. Namely, The Gospel of Conscience.” This was “the real church.’” God wants us to do what (ever it is) we sincerely think he wants us to do.

Madison jettisoned More’s Christian consensus; William Brennan jettisoned God. The claims of conscience no longer depend on their being derived from and constituting our duty to God. “Now conscience means,” Smith tells us, “something like a person’s deeply felt convictions or commitments regarding how he or she should live.” This new meaning of conscience, first formulated in American law in US v. Seeger (1965) and Welsh v. US (1970), “involved … a complete reversal—of what conscience is and why it is deserving of respect.”

Instead of being based on respect for

the supreme authority of God, or even our acknowledgment of some objective moral law that is independent of but binding upon particular persons, the protections of conscience in the modern view reflects a recognition of the inviolability or sanctity of individual human beings. Or, we might say, the sanctity of the self.

Another way to put it is the imperative: “be true to yourself,” or “be authentic.” Conscience has thus become “radical anthropocentrism,” in a devolution from the rational theocentrism of conscience as More knew it. Conscience is no longer the humble, “god-fearing” faculty of the past, but now is “proud, inflated, and free-standing.”

The great strengths of the book lie not only in the main line of argument but also in the exhilarating dialectical back and forth in Smith’s efforts to capture the core character of the three versions of conscience he lays out.

This new version is “the disintegrating conscience” of the book’s title. It undermines the claim and function of conscience in at least three major ways. First and most importantly it subverts the basis for the authority of conscience, God, in its two earlier versions. But beyond that, it has nothing to put in its place, for it also “subverts the justification for respecting [human] dignity and the self.” Smith asks, “What is the justification, after all, for asserting that every human being is possessed of some sacrosanct ‘dignity’ that requires him or her to be treated as ‘inviolable’ and with ‘equal concern and respect?’” Smith’s answer is “historical”: “The widespread communication and acceptance of the Hebrew and Christian belief that every human being is made ‘in the image of God.’” Smith can find no modern secular substitute for the now-abandoned imago Dei. The modern account of how we humans came to be does not do the job: “Darwinism … undermine[s] the case for any sort of special ‘human dignity.’” Accordingly, “human dignity” seems to function as a sort of ‘noble lie’ or ennobling fiction.” A “fragile” fiction, however.

This modern view of conscience as rooted in and affirming the noble fiction of human dignity has the further consequence of liberating the claims of conscience from the guidance and formation of standards external to the individual (as per More), unleashing the lurking potential of conscience to “dissolve society as [we] know it.” Smith sees the famous—or infamous—“mystery passage” in the Casey case (“at the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life”) as the operational meaning of modernity’s disintegrated conscience.

The third way in which the modern conscience is self-undermining is “the most fundamental”: “the modern conception of the self also has a tendency to dissolve … the self itself.” The central issue here seems to be that there are or were “traditional sources” from which the self, or identity, was fashioned, but that these, “the theistic and familial bases of identity seem incompatible with the modern determination to treat each individual as possessed of his or her own self, autonomy, and intrinsic dignity.” The ultimate consequence of this “dissolution of self” is the compartmentalization with which Smith begins his treatment of Brennan. Brennan claimed to be formed by his family and his church, but like John Kennedy, Mario Cuomo, and Joe Biden, he swore to set aside “his deepest and constitutive convictions” when operating in his “public persona,” when, for example, the Rawlsian notion of public reason would apply. This “public reason” might, however, lead us to act or support things quite contrary to what More would call conscience’s dictates.

Following Walker Percy, Smith labels the present age “demented.” As I suggested earlier—an intellectual and moral failing of modernity. Yet Smith also almost immediately moves on to “wonder what went wrong” and “who is to blame.” He points instead to “a kind of exonerating inevitability to these developments,” grounded in the nature of conscience itself.

Early in his book, Smith had identified conscience as essentially a tautology: “If something is the right thing to do, then you ought to do it.” However, as “fallible,” we do not “automatically [know] what is right.” That fact in turn leads to the melancholy conclusion that “the best you can aspire to is to do what you believe to be right.” Conscience then means: “You should do what [you believe] is right. … Conscience refers, basically, to your beliefs or convictions about what is right and wrong to do.” More had disciplined conscience by appeal to the consensus of Christians; Luther by appeal to scripture. But

In retrospect … the operations of conscience in supporting the proliferation of pluralism and the accompanying fragmentation seems irrepressible. By James Madison’s time, that pluralism was far advanced: it was not something that Madison mischievously concocted as part of a subtle, long-range effort to enshrine conscience as a unifying ideal by partially detaching it from its Christian foundation. [Was it not] “a necessary response to such pluralism? … In the same way, William Brennan’s compartmentalization relegating religious truth to the private domain … may … have thought this compartmentalization to be necessary. Necessary and also just, given the country’s religious pluralism. … What was the alternative, exactly?

Thus, Smith inconclusively concludes both the discussion of how we have gotten to where we are and what may come next. It has been an enlightening and provocative journey, despite his uncertainty about where it has ended so far. The great strengths of the book lie not only in the main line of argument as I have attempted to concisely set these out, but also in the exhilarating dialectical back and forth in Smith’s efforts to capture the core character of the three versions of conscience he lays out. His exposition is, paradoxically, sober and dazzling at once.

This is not to say that it will be persuasive to every reader, this reader included. I have my reservations, and I suspect you may also. But reservations and all, this is a book well worth reading.