The Devil Went Down to Wall Street

Economics is a happy discipline in one respect at least: it enjoys the benefits of many celebrated popularizers and highly regarded popularizations. From Frédéric Bastiat to Freakonomics, economics popularization has long been a cottage industry that successfully transitioned from pamphlets to podcasts. Popular books critiquing mainstream economics from the perspective of psychology and behavioral economics have been immensely successful both commercially and scientifically. The economist Richard H. Thaler and law school professor Cass R. Sunstein’s Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness (2008) and the psychologist Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow (2011), are the most prominent of these. In recent years, much of their evidence has been called into question by the replication crisis in psychology. Nevertheless, both Kahneman and Thaler have received Nobel Prizes in Economics for their research into questions which they successfully popularized.

Thaler, Sunstein, and Kahneman’s research has successfully shaped conversation not only in the discipline of economics, but also in public policy. Their popularizations have made that influence possible. In his new book, Hell to Pay: How the Suppression of Wages is Destroying America, journalist Michael Lind seeks to similarly shape the public policy conversation, and perhaps economics itself, with a heterodox revision of labor economics.

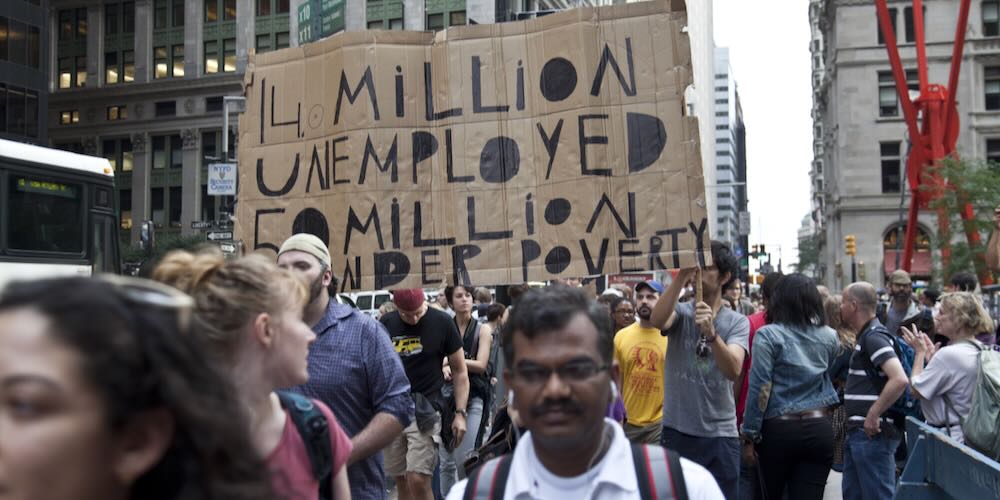

Lind opens his book with a provocative question: “What do falling fertility in the United States, a plague of loneliness and lack of friendship, bitter conflicts over racial and gender identity, and the politics of culture wars and moral panics have to do with one another?”

These are some of the leading questions perplexing American opinion writers today. A hermeneutical key that unlocks the answers to a pearl of great price. Lind’s answer?

Like cracks in a building that radiate up from a crumbling foundation, these dystopian trends are influenced, directly or indirectly, by an underlying factor: the existence of too many bad, low-wage jobs in America.

The answer is indicative of the difficulties the reader will encounter throughout the book. Rhetorical pyrotechnics must be dodged and distinctions implicit made explicit. Arguments must be followed deftly at every turn as readers realize that the author appears to have engaged his talents in a perverse literary game of three-card monte: “Step right up and try your luck finding a genuine contribution to social science!”

The reader must carefully parse Lind’s claim that the troubling trends he identifies represent an American poly-crisis which, “is the confluence of five crises: a demographic crisis, a social crisis, an identity crisis, [and] a political crisis … worsened if not caused by the fifth, an underlying economic crisis; that is the argument of this book.”

The economic crisis of “too many jobs with low wages, no benefits, and bad conditions” may or may not be causing all, some, or one of the other crises but it is “worsening” them in some way by some magnitude either in the same or different ways by the same or varying degrees. This argument, both fuzzy and weak, is buttressed throughout by rhetoric discordantly concrete and strong such as when Lind claims “America’s bipartisan elite has its own preferred solution to the problem of too many low-paying jobs: “Learn to code!” (Citation to elites saying this not included.)

Perhaps nowhere is the ratio of fuzziness to rhetorical heat more in evidence than in Lind’s discussion of the concept of low wages itself. This is never given a clear definition yet he repeatedly and fiercely insists upon seeing it as the key to understanding the American poly-crisis. The reader is told that since the 1960s, “goods-producing jobs that once provided steady jobs at good wages have shrunk from 42 to 17 percent,” that “most of the jobs that the U.S. economy has created for the past few decades have paid poorly,” and that for many new service sector jobs “wages are so low that full-time workers rely on means-tested public assistance in order that they and their families can survive.” What the reader is not told is exactly what low wages are, and how common it is for Americans to receive them.

This is a strange omission because both definitions and data are readily available from many sources. For instance, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development provides data on wage levels divided by low pay and high pay stating, “The incidence of low pay refers to the share of workers earning less than two-thirds of median earnings.” For 2022, 22.7% of full-time employees in the United States received low pay, considerably higher than the average for OECD nations which as of 2021 was 13.9%. Such data could easily be used to claim, “the existence of too many bad, low-wage jobs in America,” and the fact that it, or other such definitions or data, are not utilized makes the author’s claims appear more anecdotal or selective than necessary.

Why so large a proportion of Americans are in low-wage jobs and what effects this has on American markets and society are excellent questions, but to answer them there must be conceptual clarity. Such clarity would introduce more nuance into the discussion however as, according to the OECD data, the percentage of full-time American workers in low-wage jobs has declined from prior highs of 25.2% in 1995 and 25.3% in 2010. By at least one measure, low-wage jobs make up a smaller portion of the American labor market than they did when Lind published his first book The New American Nation: The New Nationalism and the Fourth American Revolution nearly thirty years ago.

The bombastic tone, rhetorical fuzziness, cherry-picking, and uncharitable readings of Lind’s opponents’ political, ideological, and scientific ideas are consistent throughout. He dismisses mainstream economic explanations of how wages are determined as “The Big Lie” while casually acknowledging that “obviously there is some relationship between skills and pay.” In place of the consensus of labor economists, he posits a “worker power theory of wage determination” which he grounds in the thought of Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill, and Alfred Marshall. Here Lind’s sleight of hand involves juxtaposing contemporary perfect competition models against the observations of the real-world economy made by classical and neoclassical economists. What is omitted is the fact that no contemporary labor economist would dream of believing that the real-world American labor market is identical to models of perfect competition, nor would they contest Smith’s observation that wages are “fixed by the higgling of the market.” To leave readers with the impression that the observations of the classical and neoclassical economists are at odds with the models used today by labor economists is to prey on their ignorance in the hopes of gaining a hollow rhetorical victory against scientific opponents.

What follows is a historical interlude including histories of organized labor, anti-worker employment practices, offshoring, immigration, welfare state, and education. The main rhetorical purpose here is to flesh out the rogues’ gallery beyond the bipartisan political elite and academic economists to rapacious businessmen, sinister HR professionals, globalist conglomerates, foreign workers, and dread college administrators.

Lind’s rhetorical excesses in matters of economics, social science, or history are his assets as a political operative. Even celebrated statesmen can be excused the occasional Carthago delenda est.

It is not until the eighth chapter that Lind returns to the American poly-crisis with which the book opens. This chapter is surprisingly thin given its prominence at the book’s opening. Each treatment is underdeveloped and seems to miss obvious counterfactuals. For example, Lind argues that declining American fertility is the product of greater numbers of people pursuing higher education for ever-increasing amounts of time. This he relates indirectly to low wages, claiming, “Those who do not go to college, or attend college but drop out at some point, usually must settle for inferior jobs and can never achieve economic stability.”

It’s a plausible-sounding story but stories can be deceiving. According to the World Bank Data the United States fertility rate is 1.7 births per woman while 22.7% of full-time employees in the United States receive low pay. The average fertility rate for OECD nations is slightly lower than that of the United States at 1.6 births per woman but only 13.9% of full-time employees in OECD nations received low pay. The story must be more complicated than the simple “cascade effect” from low wages to poly-crisis Lind would have us believe. These are real and urgent problems that are addressed almost as an afterthought.

If the poly-crisis driven by wage suppression was the bait, the switch is the concluding third of the book which makes the case for the rejection of the neoliberal account of globalization, worker-centered trade and immigration reform, a robust national industrial policy, a renewal of trade unionism, and a reimagining of the welfare state. This concluding section resembles a party manifesto or platform with added verve. It’s highly rhetorically effective. Lind’s rhetorical excesses in matters of economics, social science, or history are his assets as a political operative. Even celebrated statesmen can be excused the occasional Carthago delenda est.

For Lind, mainstream economics is the ideological heart of the “myths of neoliberal globalization” woven by our bipartisan political elites to obscure, “the successful American developmentalist tradition from the 1790s to the 1980s.” This “American developmentalist tradition” flows from Alexander Hamilton, through Henry Clay and Abraham Lincoln, to Franklin Roosevelt and Richard Nixon. The story woven of economic development and technical progress is a bit threadbare, leaving little room for teasing out causal relationships between historical policies and American economic development, but this story is made to bear the load of Lind’s suite of policy recommendations. This “new American System” is cast as a revival of the economic policy program that made America great, including industrial policy, more restrictive trade and immigration, new labor legislation to support labor organizing, and a reform of the welfare state away from means-tested entitlements and towards a “living-wage/social-insurance approach.” Some of these policy recommendations are more novel, such as labor reform, where Lind explicitly argues that the Wagner Act “cannot and should not be revived.” While Lind acknowledges that a simple return to America’s economic policy past is impossible, he fails to grapple with the reality that the last half-century or so of institutional changes across the globe, sometimes described as the neoliberal turn, could not be grounded simply in a conspiracy of elites. The underlying economic realities have changed.

Unlike Thaler, Sunstein, and Kahneman the critiques of mainstream economics put forth in Hell to Pay are both unserious and unconvincing. There are many valid and constructive critiques of mainstream economics on offer today, and many more to be written which will contribute to the development of the still-young science. There is even a place for outsiders to the profession such as Lind to offer such critiques. The American journalist Henry Hazlitt was both a great popularizer of economics and an incisive critic of its mainstream in his own day. Economics in One Lesson (1946) is perhaps the greatest work of economic popularization in the English language. Lesser known is his book The Failure of the “New Economics” (1959) a careful and detailed analysis and refutation of John Maynard Keynes’ General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (1936).

For all its strengths, The Failure of the “New Economics,” failed to make a dent in the post-war Keynesian consensus then dominant in mainstream economics. It would take shifting economic realities, policy failures, and institutional crises to prompt the discipline to begin to reevaluate its own understanding. This is the part of the story of the neoliberal turn that Hell to Pay passes over. As in its predecessor, The New Class War, Lind offers a just-so story of the neoliberal turn as the product of a conspiracy of an overclass that controls government, culture, and capital. Stories can be powerful, however, even if poor substitutes for the truth.

While Lind’s book is no threat to mainstream economics, he may succeed in offering an account of the world that, if not true, is congenial to the populist movements of both the left and right. Today’s populists may prove as stubborn as yesterday’s economists. Only the ground shifting beneath their feet may prompt them to reevaluate their understanding.