We must understand both the can-do spirit of America and the restraints imposed by the realities of a harsh landscape that won’t yield to mere optimism.

The Hobbesian Laboratory of the Middle East

One of America’s leading writers on foreign affairs, Robert Kaplan, is a committed internationalist and cosmopolitan. He also concedes that the American project of globalization has foundered. It was a sterile hope that history would end with the global adoption of liberal democratic bureaucratic management of peoples and markets. Where ought we to place our hope now? Imperialism.

Kaplan’s surprising thesis in his second book of 2023, The Loom of Time: Between Empire and Anarchy, from the Mediterranean to China, is that the most progressive political form is “cosmopolitan empire.” Such empires get one thing very right—geography. A cosmopolitan empire is a state overlord that grasps that geography scuttles governance micromanagers and is perceptive enough to see that tribal populism is a staple of human association. Afghanistan is an example. On the authority of St. Augustine, Kaplan contends the wise have long understood that tribes are effective political units. The Pathans, who straddle the border of Pakistan and Afghanistan, are the largest tribal society in the world. They are “an extension of an altogether rugged and impossible landscape” and have “a deep, albeit informal, level of organization, however opaque and premodern it might actually be.”

Pathans sit alongside modernity uneasily. Many places and peoples do so, and the wise policy will acknowledge this, for otherwise, those who would rule will be cast not only as Hobbes’s sea serpent Leviathan but soon exposed as toothless. The Greater Middle East has been made into a Hobbesian laboratory time and again. Great powers hoping to make others in their own image scramble ancient governance only to find themselves beached on unwieldy and jealously protected homelands. Unable to replace the order they trashed, the result is carnage for bereft peoples and prestige collapse for great powers.

The Soviet retreat from Afghanistan was the first time since the seventeenth century that the reach of the Kremlin had gone into reverse gear. America did not learn from the Soviets, even though the US project radiated out of a fortification built by the Soviets, Bagram Airbase. Wise policy, thinks Kaplan, needs to appreciate that in a goodly number of places governance is, in the words of Germaine Tillion, a “republic of cousins.”

Cosmopolitan empire is a modest political form, therefore—restrained, because it is decidedly anti-utopian. It does not seek to micromanage complex homelands; it governs with a light touch, alert that populism means agita, and worse. Put differently, cosmopolitan empire succeeds because it is not shackled to one very bad assumption that dogged American empire: the utopian belief that “the American history of freedom [is] more relevant to Syria and Iraq than Syria’s and Iraq’s own histories.”

Geography and Empire

Kaplan writes that “the depressing but undeniable fact is that empires have dominated much of political history going back to early antiquity,” and though university fashion is rank hostility to empire, “in time, that preoccupation will dissipate and a calmer view of both European and non-European imperialism over thousands of years of human history will assuredly take root.”

The Loom of Time opens in the aftermath of the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. In 1922, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk defeated a Greek army and forced the Greek population out of Anatolia. Over a million Greeks were pushed out of the city of Smyrna and its surrounding country:

Two thousand five hundred years of Greek civilization in Asia Minor abruptly came to an end. The population exchange, which also featured 400,000 Muslims being forced to move from Greece to Turkey, provided a template for ethnic cleansing in the twentieth century. For as the Ottoman Empire collapsed, a multicultural and traditional world—representing the last vestiges of early modernism—gave birth to monoethnic modern states.

Monoethnic modern states are toxic, Kaplan contends, and after a century of experimentation in the Greater Middle East a political form that keeps generating ghoulish images on social media. There is a hundred years of evidence that “empires are more natural and organic to world geography than modern states.”

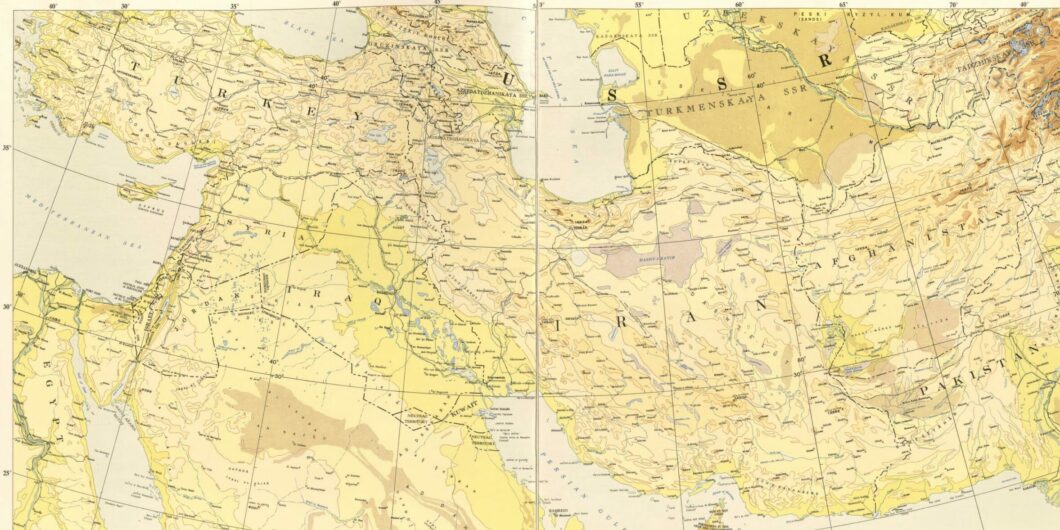

Like many other Kaplan books—he is the author of over twenty—The Loom of Time depends on geographer Sir Halford Mackinder (1861–1947), a founding father of geopolitical analysis. Mackinder made the geography of the “World-Island”—the term he gave to the vast swathe of land that comprises most of the world’s landmass, Eurasia—a causal unit. Kaplan’s Greater Middle East is a modification. As the maps at the start of the book show, the Greater Middle East scans from Hungary and Croatia in the West to China in the East with a southern boundary running from Libya and Ethiopia to India. Famously, Mackinder claimed the World-Island was the pivot of history. Kaplan follows Mackinder in making geography basic to historical change. “Egypt is more stable than its neighbors because it is a river valley civilization that does not lie athwart the historic path of conquest and migration like that other great river valley civilization: that of the Tigris and Euphrates. Because such facts imply a destiny, and destiny interferes with human agency.” The difference in the destinies of Iran and Iraq illustrates that the former is aided by geography, the latter hobbled.

Geography is the very definition of a long durée perspective, and Mackinder helps analysts range far beyond the news cycle. This explains Kaplan’s arresting remark that “Iran harbors more human potential than perhaps any civilization on earth.” Its potential begins with its geography. “Iran is synonymous with a significant geographical feature, the high-altitude Iranian plateau, protected by seas and mountains.” Iran is “geopolitically coherent,” facilitating a singular language and civilization. The Persian is the first true empire in recorded history and, despite vicissitudes, Iran has a long, sophisticated history. Kaplan is sure Iran will slough off its dictatorial clerics for even during their reign the country’s exploration of philosophy has been intense. Iran exhibits “intellectual fervour” and it is here where the learned most scrutinize the coherence of Western modernity. There is no refined reflection on philosophy in Iraq, just mayhem.

Iran has no principal rivers, while Iraq is both aided and burdened by two. As Adam Smith points out, trade brings with it many jealousies and Iraq is a migratory and trade route. For this reason, the region that is now Iraq has always been more febrile than Iran. Jealousies turned into a cauldron once the British and French got their slide rules out. Literally drawing a line across a map in 1916 with the Sykes-Picot Agreement, they broke up ancient passageways and exacerbated rivalries by creating a pro-Sunni Iraq. Kaplan reflects: “The map of the Fertile Crescent entranced me as a boy in Hebrew School, yet it made for real-life nightmares in my adulthood as a journalist.” T. E. Lawrence made famous the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire in WWI but as recompense the Allies left Arab nationalists with a “wholly invented, Frankenstein monster of a geography: forcing together as it did, mutually hostile Sunnis, Shi`ites, and Kurds.” Once the installed monarchy fell, the result was first the tyranny of Saddam’s Ba`athist totalitarianism then the bloodletting of the American intervention. Iraq is Hobbesian Laboratory 101.

Kaplan thinks the American empire is eroding—not for a lack of energy or money—but from a lack of imagination.

Hobbesian Laboratory

Doubling down on unfashionable opinions, Kaplan states: “The Hobbesian laboratory of the Middle East proves that along with empire, monarchy is the most natural form of government.” Kaplan observes that the most humane countries in the Middle East today are the monarchies of Jordan and the Gulf States. There were plenty of monarchies at one time in Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, and Syria. In the modern era, they have been replaced by militarized regimes because of the weakness of these artificial states that were originally drawn up by colonial powers. From his time embedded with the mujahidin: “It taught me the real divisions of the relief map in this part of the world, which make a mockery of the somewhat false divisions registered by legal borders.”

As is common in Kaplan’s books, chapters survey different countries under a common theme. Besides countries mentioned in this review, you will find always interesting portraits of Egypt, Ethiopia, Syria, and Turkey. Chapters close with Kaplan’s fact-finding travels, but each begins with a summary of geography and history. Summaries rely on significant scholarly works that are typically older, humanistic classics rather than contemporary data-driven academic articles. Kaplan champions “writers long out of fashion,” the likes of Edward Gibbon, T. E. Lawrence, and Elie Kedourie. As well as Mackinder, Kedourie (1926–92)—an Oxford-educated Jewish Baghdadi and member of the British Academy—is basic to the book’s reasoning.

Kaplan describes Kedourie as “a reactionary with decades of evidence to back him up.” Author of a classic work on strategy, The Chatham House Version, Kedourie skewers British colonial failures in the Middle East, lamenting the artificiality of the borders drawn about peoples to make modern states and proposing monarchy as a natural “storehouse of devotion and loyalty,” a “dyke against bestiality.” Throughout the region, however, artificial sovereignty subverted natural sovereignty and the glue turned to was tyranny. Kaplan recalls his first time crossing the border from Syria into Iraq, both Ba`athist tyrannies: “Yet I was unprepared for the paranoia and repression that I felt in my throat and in my stomach my first moments in Iraq.” After years of battling clinical depression for his role in recommending the Iraq War, Kaplan is grimly convinced that even tyranny is better than the anarchy he witnessed and reported on during the Second Iraq War. In light of Mackinder’s analytics, “Iraq was even more artificial than Syria, and therefore its politics were even more brutal.” The front matter includes an attic relief with an ancient putting a sword through a lion. Even Saddam is preferable to the lion of chaos.

Political form contoured to the land can humanize, however. The loom of time motif conveys that progress in humane governance is discernible, albeit not in a matter of years, nor decades even, nor in a Western sense. Kaplan reports that Singapore is the example invoked by current Saudi leadership—liberalization in the confines of an autocratic bureaucratic state. The current royal in control in Saudi Arabia, MBS—Mohammed bin Salman al Saud—is a stickler for detail and is particularly interested in aesthetics. Large state dinners for dignitaries have been jettisoned, replaced with intimate meals with after-dinner walks for close conversation. But make no mistake, behind the refined tête-à-tête is a brutal security state. Of course, the history of MBS is well known, as well as the infamous fist-bump. A tough, stomach-churning truth comes into focus: “Saudi Arabia proves that brutality is not necessarily self-destructive or destabilizing for a regime, as long as the regime delivers an ever-improving quality of life for the overwhelming majority of its citizens.”

A Reluctant Imperialist

Kaplan thinks the American empire is eroding—not for a lack of energy or money—but from a lack of imagination. Despite US failures in Iraq, Syria, Libya, and Afghanistan, policy elites are wedded to liberal idealism—making American political history normative for the globe. This refusal to reimagine is a function, as he brutally puts it, of Washington’s many “cocktail-circuit minds.” Analytically, what needs to change? To think at length about the difference between natural and artificial political forms.

“Left alone, the Fertile Crescent is a natural and beautiful landscape that makes sense on a topographical map. But when laid across a modern political map, it begins to explain why Iraq and Syria, for instance, became the monstrosities that they did.” Still, empire disquiets Kaplan. He is not postliberal. Devoted to Gibbon, he is an Enlightenment cosmopolitan. America has a tradition of republican liberty that must be cherished but US policy must allow others their monarchies and tribes, with their own peculiar brands of consultative governance.

Kaplan is comfortable with a postmodern era in which ancient models of rule continue alongside “emerging global civilization expressed through social media and the internet.” Kaplan does not predict this new era will be peaceful, but it will be civilization-building regardless. He does not say, but a historical parallel might be the Pax Romana, where the legions were in charge and built impressively but tolerated a vast array of customs and mostly left peoples to their own devices. China stands fair to develop an effective empire. Kaplan was probably the first Western writer to draw attention to the repression of the Uighurs. Itself an empire, China demands internal cohesion. Beyond its borders, however, it shows little inclination to export the utopian Marxist philosophy that is its official national doctrine. Like the Romans, the Chinese do not seem intent on morally reforming others, which is not to deny China wants to rule. Expanding across Eurasia, its Belt and Road investments come with forts staffed by ex-Chinese military and Chinese medicine clinics and language schools. Sinica hard and soft power is on the move.

According to Kaplan, the future has a playground and the winner will not be a utopian:

The Greater Middle East is the fight zone for these ghost empires: the vast puzzle piece that China needs to command, if it can link its budding commercial outposts in Europe with those in East Asia. Here, states are often weak and in key places nonexistent, and democracy has generally failed, at least so far. … It is time to explore further this harsh geography that will be a register of future great-power struggles across the globe, as it always has been in the past.

Should China’s leadership learn from Hobbesian Laboratory 101 and modestly defer to homelands and the legacies of empires past, then control of the World-Island may well fall to them.