Russian Literature's Prophetic Voice

Looking back on his early twenties, Fyodor Dostoevsky wrote that “many, many of the young people of the day seemed to be filled with a spirit of some sort and seemed to be awaiting something.” It was 1845. No one quite knew what to wait for. But surely some explosive change was coming. Everyone around Dostoevsky could feel it, like a building static charge: something was going to happen. In an instant, unforeseen though long-awaited, the future would fall away from the past.

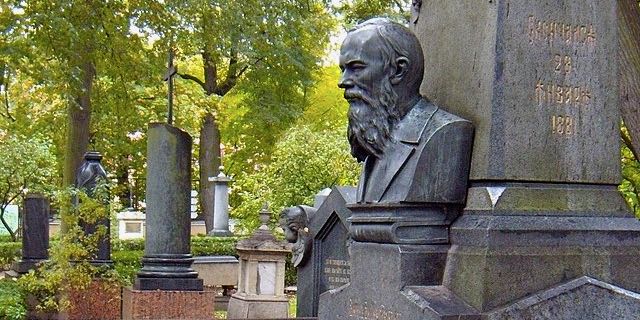

Young Fyodor would certainly see his share of decisive events, starting that very summer. One evening in May, the wide-eyed luminary Vissarion Belinsky sent for him by way of mutual friends. Professor Gary Saul Morson describes the episode early on in his beautiful new book, Wonder Confronts Certainty: Russian Writers on the Timeless Questions and Why Their Answers Matter. Belinsky greeted Dostoevsky’s first novel, Poor People, with a characteristic ecstasy of raw excitement. “Have you yourself comprehended all the terrible truth you have shown us?” raved Belinsky to the bashful young artist. In a matter of days, this obscure doctor’s son became a cause célèbre among the Bohemians of St. Petersburg.

The high-minded prophets of that fashionable crowd were all holding their breath for the moment when History would surge toward its grand conclusion. But Dostoevsky’s achievement was not to tell the future. It was to describe the present. The “terrible truth” of Poor People was the one already unfolding in the streets, within the modest compass of the city’s low-rent apartments. Theorists could predict all they wanted, but Dostoevsky could see.

“The writer as prophet is not someone with a lucky gift of foresight,” wrote the classicist Bernard Knox. He is “someone who foresees only because he sees, sees clearly, unmoved by prejudice, by hopes, by fears, sees to the heart of the present, the actual situation.” It is a poignant irony of intellectual life that novelists often foretell the future more accurately than theorists, because they are not trying to. They are just depicting the human realities of the present moment.

The rest of us are always looking backwards or forwards, fighting yesterday’s wars or anticipating the next likely cataclysm. Great writers, though, see the germs of everything that could happen tomorrow by looking in frank amazement at what is already happening today. As Augustine observed long ago in his Confessions, nothing really exists for us except the present—so the signs of what will come, if they are anywhere, can be found in the here and now. Ideologues can only spin out their doctrines into brittle syllogisms, shrugging off the quirks of real people and the accidents of real life as so much irrelevancy. But for a novelist, the quirks and the accidents are the point.

This contrast—between the ironclad certainties of the revolutionary and the open-hearted observations of the artist—runs through the center of Wonder Confronts Certainty. Assessing the literary contributions of Russian thinkers in Dostoevsky’s generation and afterward, Morson pits the humane wisdom of storytellers against the arrogant declarations of political activists.

Dostoevsky’s own prescience would soon grow legendary. Suffering and misfortune distanced him from the confident radicals of his youth, until he could see what crazed extremists they would become. But Dostoevsky was not alone. Many of the poets and playwrights in Morson’s pages exhibit a veritable second sight, penetrating into the heart of issues that would motivate the rise of Soviet totalitarianism. Through the sheer force of their honesty, these storytellers became visionaries.

Morson refrains from mining his subject matter for contemporary “relevance.” He doesn’t have to: the relevance is there, and he can let it speak for itself. The “timeless questions” of his subtitle really are timeless. But they arose for Russian authors within a particular social context, which gave them a distinctive weight and character. Morson’s way into them is to explain how Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Chekhov, Turgenev, Solzhenitsyn, and others came to grips with the existential problems of their moment. He does this with such loving care that the concerns of these bygone writers become our concerns.

A much-beloved and decorated professor of literature, Morson has been teaching at Northwestern since the ’80s. This new study picks up some themes from his many earlier books: Narrative and Freedom (1994) was a meditation on the tension between literary artifice and open-ended choice; Minds Wide Shut (2021) was a forceful critique of modern political dogmatism and its constraints; and Wonder Confronts Certainty gathers these various career-long concerns into a cumulative survey of Russian literature.

Simply by revealing people as they are, the novelist explodes any effort to capture their behavior in an equation or a theorem.

It is a bravura performance. Morson’s knowledge of his field is enormous. With the patience of a practiced educator and the expansive understanding of a true humanist, he ranges widely among a huge cast of characters. Having introduced the distinction between artists and ideologues (“Part One: The Disputants”), he profiles the various casts of mind that each category produced (“Part Two: Three Types of Thinker”). Then, in the book’s largest section (“Part Three: Timeless Questions”), Morson brings his major and minor players into dialogue with one another on what Dostoevsky called “the accursed questions”: grand debates over fate versus free will, scientific analysis versus spiritual satisfaction, individuality versus social control.

Nineteenth-century Russia as Morson describes it was a kind of slingshot civilization, catapulted straight into modernity out of something not unlike a Medieval economy. Tsar Alexander II liberated the serfs in 1861, suddenly ending a form of feudalism that had limped on well beyond the triumph of capitalism in Europe. The century hurtled by in a blur of accelerated development; only a prodigious generation of literary chroniclers could possibly have kept pace with it. Russia’s artists rose to meet the moment. “Russian literary history is ‘telescoped,’” writes Morson. Starting with Alexander Pushkin’s verse novel Eugene Onegin in 1823, masterworks cascaded thick and fast from the Russian press: “Imagine French literature beginning with Balzac.”

In the midst of all this rapid-fire change, one question rang out starkly. It was posed in the title of Nikolai Chernyshevsky’s 1863 utopian tract: What is to be Done? For Chernyshevsky, there could only be one answer. As Morson paraphrases it, “One and only one thing can happen at any given moment.” Loosed suddenly from her restraints, Russia would rocket past Western Europe in a rush of pent-up energy, bypassing capitalism and heading straight toward a gleaming socialist future. “No one will ever be poor or unhappy again,” Chernyshevsky wrote. Here was a consummation so devoutly to be wished that any means of hastening it would be more than justified.

Newtonian physics and Darwinian evolutionary theory had wafted over from England by way of Germany and France, blending headily with Marxism along the way. Newton’s most celebrated French interpreter, Pierre-Simon Laplace, had dreamed of a mind that could know the velocity and location of every particle in the world—a mind before which “nothing would be uncertain. The future, like the past, would be present to its eyes.” The most devoted Bolsheviks flattered themselves that they had attained exactly this sort of infallible foresight.

If the world is nothing more than matter in motion, then time itself can only roll with clockwork certainty toward the glorious breaking of a revolutionary dawn. History most definitely has a right side, and woe betides those who are not on it. “Dialectical materialism had supposedly demonstrated that the inevitability of communism derived from teleology inherent in matter itself,” Morson explains.

Vladimir Lenin adored What Is to Be Done—he wouldn’t hear a word against it. Like all fanatics, he knew beyond doubt that what must happen would happen, and what would happen was what his grand design foretold. There was only one problem: other people. Here is where “wonder confronts certainty” as in Morson’s title. For those other people are the ones the novelist is always wondering at. Russian realist novels take as their subjects those maddeningly loveable others who refuse to behave like atoms or widgets.

Morson is at his most eloquent when he is insisting on this: “Individuality is essential to humanness, as it is not to molecules,” he writes. “Novels presume the fascinating uniqueness and absolute unrepeatability of each person, who cannot be reduced to material causes.” Simply by revealing people as they are, the novelist explodes any effort to capture their behavior in an equation or a theorem.

Take for instance Pierre Bezukhov of Tolstoy’s War and Peace, who tries and fails to discover a secret code for understanding history by attaching numbers to the names of great men. There is something in Napoleon that can’t be exhausted by addition or multiplication—which implies that there is something in Pierre that escapes mathematical accounting, too. “When Pierre at last attains wisdom,” Morson writes, “he abandons the quest for theory.”

In 2018, Vladimir Putin unveiled a statue of Solzhenitsyn on the centenary of his birthday. But by then, of course, Solzhenitsyn had been safely dead for some ten years.

The irrepressible complexity of real life was what the architects of the Soviet regime could not abide or admit. The one thing they could never fit into their perfect template for human happiness was humanity itself. In 1918, Lenin appended the words, “Find tougher people,” to a decree of death for no fewer than 100 peasants who resisted his efforts to confiscate their grain. There, in one ruthless command, was a foretaste of everything to come. The millions dead by famine, the gray drudgery of the commune, the sadistic horrors of Stalin’s Gulag: it would all flow naturally from the implacable hearts of men who knew their ideas were right. The people were the problem.

What has endured from those days is not socialist theory, which changed by the hour, but the mournful testimony of literary observers. The greatest among them had the courage to record the truths of the human heart when it became suspect or even illegal to do so. Their words have long survived the total collapse of the regime that tried everything to snuff them out. Stalin lies dead in ignominy; Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago is immortal.

The world has no final solution: those who admit this give up on perfection and gain insight in return. Morson cherishes a particular fondness for Anton Chekhov, who wrote that “it is time for writers … to admit that you can’t figure out anything in this world.” Perhaps not—but by making that admission, a writer sees the present and the future more clearly than any Party apparatchik ever could. Like Coleridge’s ancient mariner, a great artist is both sadder and wiser than those who have suffered less. Morson quotes the 2015 Nobel prize winner Svetlana Alexievich: “Suffering is our capital, our natural resource. Not oil or gas—but suffering. It is the only thing we are able to produce consistently. … But great books are piled at our feet.”

The Soviet Union is gone, but the twenty-first century has some implacable certainties of its own to contend with. We all love hearing truth spoken to power—unless we’re currently in power and the truth hits too close to home. In 2018, Vladimir Putin unveiled a statue of Solzhenitsyn on the centenary of his birthday. But by then, of course, Solzhenitsyn had been safely dead for some ten years. One wonders whether he could face the great man now, as the state asserts ironclad control once again over artists and reporters. The Gulag Archipelago is mandatory reading today in Russian schools, yet scores of monuments to none other than Stalin himself have gone up under Putin. Yesterday’s dissidents are held in honor. Today’s—journalists like Anna Politkovskaya or defectors like Alexander Litvinenko and Sergei Skripal—die under mysterious circumstances.

These sorts of contradictions and hypocrisies, though extreme in Putin’s Russia, are not exclusively limited to within its borders. The human heart being what it is, lip service to “radical truth telling” can always sit comfortably alongside remorseless small-mindedness. This was clear enough when Putin launched his invasion of Ukraine and Russian art became fodder for a ludicrously counter-productive species of protest. Netflix scuttled an adaptation of Anna Karenina. Orchestras and theaters replaced Russian performers. An Italian college toyed with the idea of postponing a course on Dostoevsky. Within Ukraine itself, this sort of nationwide antipathy might make a certain degree of sense. But in the West at large it reveals exactly the sort of fatuous self-regard that comes from too much confidence and too little real understanding.

Today’s intelligentsia are more than willing to reduce the world to their own simplistic formulas—which is why Russian literature remains a stumbling block for authoritarians both aspiring and actual. It is also why Morson’s labor of scholarly love feels so timely. There will probably always be new despots ready to sacrifice mankind on the altar of their convictions. It follows that simple artistic delight in the variety of human affairs will always remain fresh and subversive. Today’s certainties will sound dated and foolish in a year’s time. But wonder is forever new.