The Quest for Fraternity

“A specter is haunting the modern mind, the specter of insecurity.” So wrote Robert Nisbet in his classic The Quest for Community, published in 1953 describing “the preoccupation with personal alienation and cultural disintegration” at midcentury. The late Rutgers University Professor Wilson Carey McWilliams would agree (without referencing Nisbet) twenty years later in his magisterial The Idea of Fraternity in America (1973), surely one of the most impressive published dissertations of the twentieth century. The fiftieth-anniversary edition from the University of Notre Dame Press is well worth the long read, and it is long, clocking in at 624 pages of well-written, if occasionally meandering, prose, not including the index and footnotes. The new edition begins with an introduction by the political theorist Susan McWilliams Barndt, daughter of the late McWilliams, with personal anecdotes and insights that bring the author to life and help to place his queries and concerns in personal and professional contexts. Reading the book also brings into relief the work of McWilliams’ most prominent student, Patrick Deneen.

Barndt’s context is helpful in identifying the particular “new left” twist of McWilliams’ concerns for fraternity similar in some ways to Nisbet’s more philosophically conservative perspective (in the nineteenth-century meaning of that term). The comparisons between the two are uncanny. McWilliams was a graduate student involved with the new left at Berkeley, before the new left took an individualist turn in the late 1960s. A few decades earlier, Nisbet completed his graduate studies at the same institution, finishing in 1939. Some of Barndt’s insights are more personal. My favorite explains the length of the dissertation. Anyone who has been through the dissertation rite of passage into academia will chuckle that the length of the volume is in no small part due to McWilliams’ friendly competition with a fellow graduate student to write the lengthiest dissertation. (McWilliams lost, but the resulting book is actually the abridged version of the original dissertation!)

Like reading Nisbet’s Quest seventy years on, McWilliams’ insights fifty years on appear “even more of a revelation now than when they were first written, because of how urgent and fresh they feel today.” This is because the book inquires relentlessly into the core value of community that animates the best thinkers on both left and right. Just as Nisbet is difficult to pin down politically, so is McWilliams. For example, while a man of the left, McWilliams is critical of the progressive claim that democratic engagement has increased throughout American history. True engagement by the people has never been as difficult as it is today. True responsiveness by the government to the people has never been so lacking. It is as if the democratic quality of American governing institutions declined in proportion as the democratic quantity of voters increased. The closer we moved to universal suffrage, the further we went from responsive democracy.

McWilliams is encyclopedic in his discussion of a wide variety of thinkers and movements. A review cannot possibly do justice to all of his entries and insights. Religion gets an especially sympathetic treatment, while prominent thinkers and movements from Ralph Waldo Emerson to the New Deal get the hammer. Amen to that. Again, I sense a bit of Nisbet in McWilliams in his willingness to reject easy ideological answers. Nisbet could find insight in Proudhon and Kropotkin nearly as easily as in Burke and Tocqueville; he could criticize FDR and Wilson as readily as Reagan and Eisenhower. Nonetheless, just as it did for Nisbet, the spirit of Tocqueville animates every page. Indeed, every chapter opens with a Tocqueville epigraph.

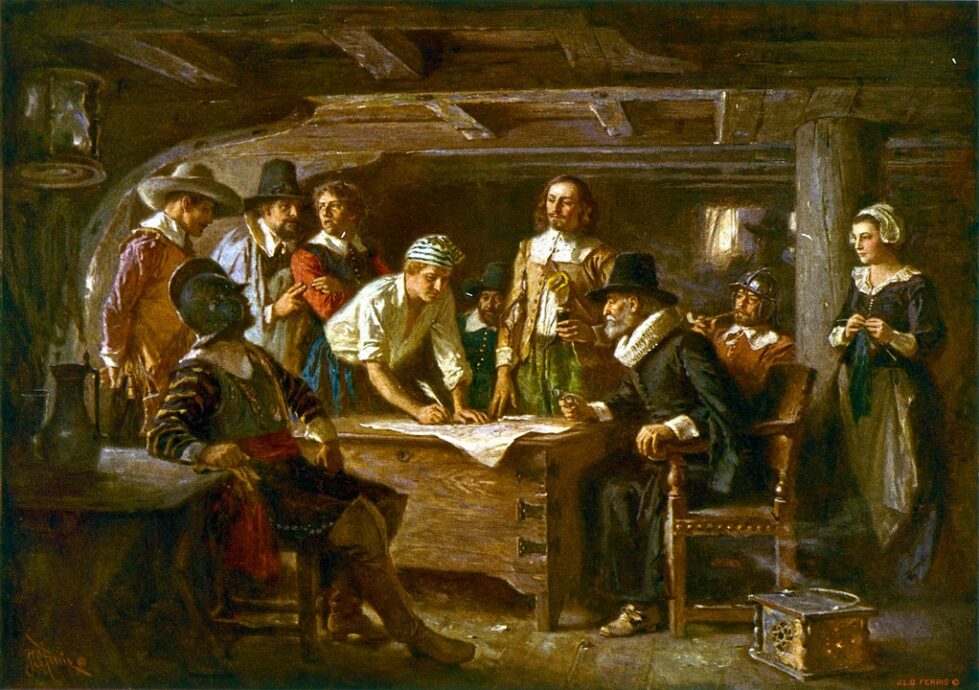

The core thrust of the book is that the framers of the Constitution (like Russell Kirk, McWilliams thought the founding a longer and earlier period that predated official Constitution-making) constructed an order entirely upon a foundation of competitive individualism in such a manner that it made true fraternity impossible. McWilliams’ premise is that liberty, equality, and fraternity are the core political values of modern political order, but while we have run with modern interpretations of liberty and equality, we have left fraternity by the wayside. Rarely spoken, even less theorized, it has haunted the American imagination. The language of liberal politics betrays this orientation. Liberty and equality show up repeatedly in the founding and throughout American political history, but rarely fraternity. It is the “ambiguous ideal,” present but undefined and in constant tension with the liberally defined values of liberty and equality.

In such a liberal spirit, the American framers “crafted a massive, impersonal regime that works to erode relationships, destabilize communities, and inhibit collective action.” These words are Barndt’s, not McWilliams, but they capture perfectly the thrust of McWilliams’ thesis. The framers of the Constitution set America on a course that would expand and transform politics and economy around the value of competitive individualism, excluding from our political and economic spheres the potential for fraternity. Barndt explains that the problem is that we all “long to be recognized by and live in relation with others. But modern liberalism makes it hard for us to put words to that longing.” The framers embedded their liberalism in our constitutional, social, and economic orders, making it hard for us to live in meaningful relation to others. On a personal note, Barndt records that McWilliams often complained that our liberal society was structured to make good parenting difficult. The claims of a competitive economy clash directly with the claims of parenthood. Every person must choose between the demands of the liberal economy and the obligations of the family. Barndt notes that in his own personal struggle McWilliams chose repeatedly—to his eternal credit—the latter.

McWilliams points out that the religious structures created by the Puritans did last well into our present age, even as they endured constant siege.

What is Fraternity?

The first several chapters lay out the sociological basis for fraternity. It reads very much like an academic dissertation in getting the historical, etymological, and philosophical definitions, concepts, and distinctions out on the table. Fraternity conceptually is inherently bound up with the idea of kinship. If groups are the basis of politics, and they must be, then the basis of each group is what individuals have “akin” to each other. With the invention of political society, we may have moved beyond kinship as the binding force of community, but not kinship as a social model. We must have something that brings us together beyond personal interest, something like “brotherhood.” Fraternity as a concept remains relevant in modern politics because it is essential to both ancient forms of kinship as well as to modern contract theory. Just as in a kinship society, brothers are all equals in their inferiority to the father, so we under the social contract are all inferiors to the sovereign and thus brothers in a similar way. A tension that McWilliams never resolves is between the assertion of universal brotherhood of all men and the need for concrete fraternity, probably bound to local institutions. This tension and the failure of any thinker or historical movement to resolve it drives much of the analysis.

Another important frame in the discussion of fraternity is whether it is the means or the end of political life. Do we instantiate the political principles of equality and liberty to become brothers or do we undertake fraternal activities to realize equality and liberty as political ends? Like many twentieth-century theorists, McWilliams juxtaposes the ancients and the moderns on his subject matter. The moderns, including the American framers, thought equality and liberty were the means to fraternity. The ancients thought fraternity the means to equality and liberty. For McWilliams, the underlying existential reality is the brotherhood of all men. Thus our politics as well as our social and economic life must be suffused with fraternity as part and parcel of everything we do, the means of fraternity inextricably bound to the ends of politics.

During this discussion, McWilliams discards several misguided attempts to describe fraternity or community. One is the “group mind” concept, an unholy progeny of merging romanticism and behaviorism causing social theorists to see traditional societies as “naturally communal.” Ancient peoples did not have any more of a “group mind” than modern peoples do. Rather, they were more “conscious of their dependence on other men,” but not more communal as such. “Iron-clad custom” may make a society appear uniform, but community must always be relations of persons and there is always an element of individual choice. Every generation must renew again the traditions of its community and enter into its inheritance through individual action. Fraternity itself as the bond of brotherhood must recognize at its core the separate individuals who compose the bond and choose brotherhood.

McWilliams’ historical account begins, as do all on anything “in America,” with the Puritans where the covenant was front and center, a fraternal bond needed to sanctify sinful beings. The Puritans were explicit on this point. Individual spiritual reformation required fraternity as readily as physical survival. McWilliams’ discussion draws attention to the sophistication of the Protestant account. Men need fraternity for nature, civil society, and religion. Fraternity for nature to survive physically in a world of want, for civil society to live in peace and prosperity, and for religion to discipline one toward a holy life. The spheres identified correspond to various institutions beginning with the family, the most fraternal of all units, and even more exalted than the state. For the Puritans, “the good city becomes a series of interlocking fraternities, binding magistrate and magistrate, magistrate and minister, and magistrate and citizen.” We might also say, binding minister and citizen, and citizen and citizen.

The Judeo-Christian concepts incorporated by the Puritans possessed a wisdom the Enlightenment did not. They understood the necessity of fraternity in their covenants between God and man and between man and man. How different would nineteenth-century religion be epitomized in liberal theology and Mormonism, both individualist to the core? The Social Gospel talked of fraternal duty, but it rejected “the wisdom of traditional theology” for social reform, which was faster and easier than the work of fraternal sanctification. The Puritan covenants would struggle against the liberal structure of modern society, even if they predominated until the founding period and exerted influence through civil society for generations more. McWilliams points out that the religious structures created by the Puritans did last well into our present age, even as they endured constant siege. The relentless barrage of liberalism damaged their fraternal quality and reduced their influence in society.

America Against Fraternity

McWilliams believed the very structure of American liberalism militates against fraternity in all its forms. Once the Constitution of the federalists took hold, its underlying assumptions of competitive individualism, like a solvent, wore away at the fraternal bonds of religion. The influence upon Patrick Deneen’s Why Liberalism Failed is obvious here. But also the influence on Barry Alan Shain’s The Myth of American Individualism: The Protestant Origins of American Political Thought. Shain too argues that the essentially communal nature of American political order gives way to competitive individualism in no small part due to the Constitution of 1787. The spirit of McWilliams is strong with these ones.

Time for a critical observation. McWilliams, like others, is not giving due regard to the framers’ assumptions on the fraternal bonds as core to society. The right to covenant is a right residing in “the people.” Covenanting is not autocratic, as McWilliams points out. It is also a right that underlies more in our Constitution, especially our Bill of Rights, than McWilliams and others recognize. Many, Nisbet included, have lamented that the framers were too embedded in modern contract theory to understand the importance of towns, churches, and fraternal societies to stable and meaningful community. But this does not give adequate attention to the circumstances under which the framers were working. The debates between Anti-federalists and Federalists were over the relations between state governments and federal governments, touching not at all upon town covenants. Forrest MacDonald notes that in some ways the entire Federalist/Anti-Federalist debate was a sideshow, ignoring the thousands of governments at the local level, which held true power over individuals’ lives. Furthermore, as Michael Zuckerman and Donald Lutz both pointed out in their respective studies, “the people” as a political term was a reference to the towns arranged around their civic and religious covenants. The US Constitution and the states took those covenants for granted. The much-maligned (by some) Bill of Rights references the “right of the people” precisely in the contexts where fraternity prevailed in free assemblies, local militias, and households. I would submit that when the American framers used the term “the people,” they often meant something concrete, local, and, most importantly, fraternal. McWilliams is mistaking the views of the framers for their liberal and republican interpreters.

That aside, McWilliams demonstrates how the “ambiguous ideal” of fraternity underlies many of the social debates and writings of major figures throughout the history of our Republic. Concern that a healthy political community required the small towns of the rural countryside drove Jefferson’s agrarianism. As commerce grew, agricultural communities declined. Jefferson feared rightly that the fraternal republic would not survive the commercial revolution. The federal government made new states, not on local affections or history, which had formed the original thirteen states, but on federal policy. The new states were territorial aggregates made into political entities by federal fiat. They were not political communities as such. The growing population made local government difficult in the way it had been conducted during the colonial and early constitutional periods. Decades later, Tocqueville too would observe that the growth in cities made the town meeting impractical. Jefferson saw that cities were only commercial centers, its citizens there only for financial status, not community. For McWilliams as for Jefferson, the commercial republic was Hamilton’s and Madison’s goal in the Constitution. It emphasized the competitive individual at the expense of the social. Perhaps the American framers could have made different decisions and designed a better republic, one suffused with fraternity.

The transcendentalists’ emphasis upon “oneness” and vague spirituality was an attempt at securing the fraternity of man for an exploding population. They failed to concretize their desire for fraternity, indeed, their thought consisted of “hostility to fraternity among men in the name of the fraternity of mankind.” Ralph Waldo Emerson further undermined fraternal possibilities by his hatred of groups. McWilliams writes,

Groups, localities, and even fraternal relations might encourage men to follow a by-road which would delay the course of things. True statecraft would give these concrete groups scant and hostile attention; it would seek to make it easier for “events born out of prolific time” to enter and shape American life.

The deep-seated individualism of Emerson and Henry David Thoreau under the fraternal guise of universal oneness, treats friendship, at best, as a means to universal friendship, an abstraction, or at worst, a distraction from the true path to self-discovery.

If Emerson and Thoreau make the self too separate to ever have fraternity, Walt Whitman’s fraternal dream abolishes the self altogether, making fraternity impossible from the other side. Whitman’s mistake is the inversion of Emerson’s and Thoreau’s. For Whitman, “fraternity is conceived as selfless community or total tyrannical domination. Neither possibility is equivalent to fraternity, which is communion between separate selves.” There is no real communion in Whitman, just warmth toward one another. In a delightful turn of phrase, McWilliams describes Whitman as the “prophet of himself, not of fraternity.”

Perhaps the only source of hope is that the quest for fraternity, like Nisbet’s “quest for community,” will not be denied.

The transcendentalists aren’t the only derailment in the nineteenth century. McWilliams sees that proclivities to racism and imperialism were evidence of political decay. Fraternity is in a bad way when its achievement depends on domination of or hatred for others. Fraternity must be for the love of the brother, not hatred of another. Mark Twain understood this. He saw that the individual only grows through deep friendship, fraternity. Hence, the moving friendships between Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn and Jim.

A Future Revival?

The book is full of offhand insights. One is that a society’s values will dictate the terms of fraternity. Fraternity can exist between economic classes, but only if neither the rich nor the poor value money. If either centers money (or lack thereof) as core to their identity, brotherhood between the haves and the have-nots will be impossible. If acquisitive individualism is the highest value, as McWilliams thinks it is today, then that will make certain fraternal arrangements impossible. If religion is the highest value, a different set of fraternal arrangements becomes possible. The problem with liberal individualism, unlike religion, is that there is no fraternal arrangement that can satisfy the individualist requirements. It is inherently anti-fraternal and infects all areas of politics, economics, and society.

One of the more satisfying biases McWilliams exhibits is his recognition of the damage romanticism does, seeing its poison everywhere. Here his critique is similar to the New Humanists, Irving Babbitt, and Paul Elmer More. However, there is only a brief and unsatisfying discussion of Babbitt and More, oddly missing citations to their work (only Babbitt’s Democracy in America appears in the bibliography). McWilliams is critical of Babbitt and More, dismissing their work as only a recapitulation of the Federalist creed of property, individual liberty, and Enlightenment values. Leaving aside that oversimplification of their work, he fails to consider here and elsewhere in the book the role of property in securing fraternity against an atomized world. Nisbet is keen on this point in his discussion of the conservative reaction to the French Revolution. Property was essential to a corporate entity, whether filial, religious, or fraternal, in maintaining its authority and independence of royal or political power, serving as a financial and (possibly literal) motte against outside intrusion. Property provides place to community. Admittedly, Nisbet is discussing European developments and thought, not American, but its relevance to fraternity stands especially because Babbitt and More were drawing from the same historical insights as Nisbet and applying them to the American context. Their understanding of property’s role in community and civilization has a better and more communal pedigree than McWilliams’ radicalism and anti-Lockeanism admits.

In some ways, this is a depressing book, although Barndt insists that McWilliams had a great deal of hope that American politics could (even if it will not) revive fraternity as an essential political ideal and practice. The hopelessness evident here might explain Deneen’s transition from Why Liberalism Failed to Regime Change, the first a return to front porch Tocquevillianism and the latter to something more drastic and revolutionary. The McWilliams of The Idea of Fraternity would have disliked the latter, but what then is McWilliams’ solution to revive our lost fraternity? Not progressivism, the child of liberalism, with its hostility to intermediate groups. Its policies did not destroy but did undermine the nuclear family. McWilliams writes, “The traditional institutions and beliefs which liberalism had taken for granted, or seen as the ‘instinctive’ expressions of ‘natural man,’ were perishing. Only the conjugal family remained strong, and it was radically destabilized.” He spoke too soon! If only he could see it now.

John Dewey’s proposal that the state offer group memberships elides the voluntary nature of fraternity. Labor unions are contrived fraternities, generating little real brotherhood. “Neighborliness” of the early and mid-twentieth century is not fraternity, but a dim shadow of it. The New Deal was a failure in fraternity because it generated resentment of liberal compassion. What Americans really wanted in the turmoil of the early and mid-twentieth century was fraternity, not organization. All of these solutions are themselves bound by the Enlightenment and thus fail to elevate fraternity, conceding too much to liberty and equality. Even the radical counter-culture of the 1960s is just “negation which is bound up with the affirmation it rejects, the underside of liberalism rather than an alternative to it.” The individualist new left could not incorporate fraternity as a way of being any better than the society it hated.

The sobering problem for Americans today is that in the past, McWilliams writes,

When liberalism and modernity failed them, there was another world to which they could repair. Made most visible by the churches, the ethnic groups, and the small communities, it was what Americans meant when they spoke of “home.”… Now, however, the groups which supported that tradition are dead or dying, as liberal society comes more and more to resemble that blank sheet which its great prophet asserted was the natural beginning of men.

I wish that McWilliams had read Nisbet’s 1973 book, The Social Philosophers, before publishing (and vice versa). I wish each could have been enriched by the other. There Nisbet draws from the pluralist tradition to describe a type of community where fraternal groups would be able to thrive. McWilliams is dismissive of the pluralism of Harold Laski as an appeal to myth and the pluralism of Arthur Bentley because it shifts attention from the public to the private, thus undermining the public-spirited politics of fraternity that McWilliams advocates. Nisbet’s appeal owes something to the English pluralists as well as American constitutionalism, the conservatism of Burke and Bonald, the liberalism of Tocqueville and Lemannais, and studies of social history revealing that a version of political order now dominant cannot but crush fraternal groups in all their possible manifestations. McWilliams’ suspicion of the private is surprising because it shows an acceptance of the private/public distinction key to the liberalism he rejects. But the private, properly understood, might be the very sphere where fraternity can thrive and spill over into the public because it is shielded from a liberal public square hostile to fraternity. Likewise, the pluralism Nisbet discusses is one that is recognizable in the thought and world of the framers and their constitutional order, even if it is not in many of the republican and liberal interpreters of the framing over the last half-century and more. It too recognizes structurally many places for everyday fraternity.

Perhaps the only source of hope is that the quest for fraternity, like Nisbet’s “quest for community,” will not be denied. McWilliams writes, “Some minds turn to, and other voices speak, the old language of fraternity, and that is only testimony to the fact which the idea expresses: that fraternity is a need because at a level no less true because ultimately beyond human imagining, men are kinsmen and brothers.”

That may be a comforting thought.