The veterans of Donbas embody the aspirations for a functional, democratic Ukraine.

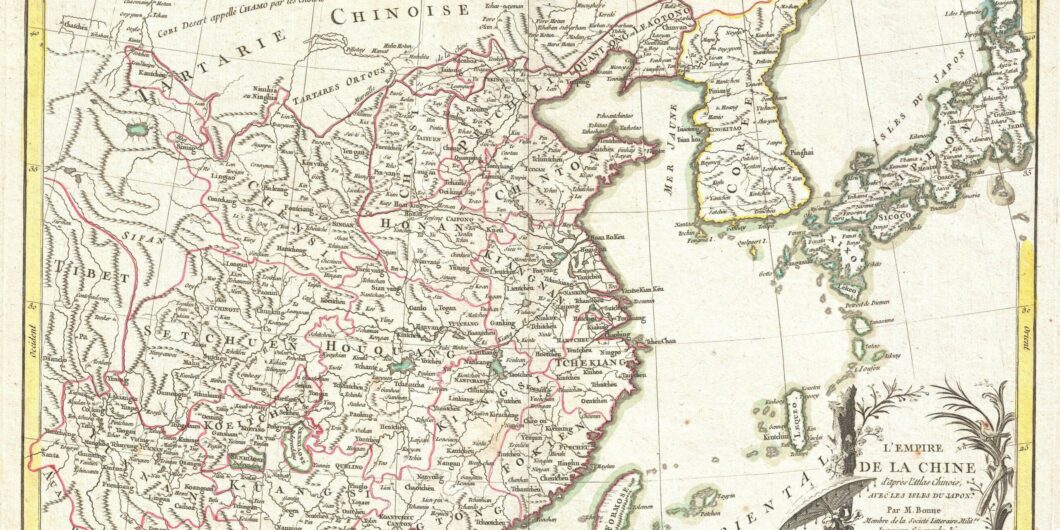

The Race for Asian Hegemony

For one hundred years, in what became known as the Great Game, Britain and Russia competed for influence in Central Asia. Russia wanted new territories and markets with which to secure her great power status. Britain wanted to protect her most valuable colonial possession, India, against what she feared was a long-term Russian expropriation plan. The two empires sent spies into the vast square stretching from the Strait of Hormuz and the Caspian Sea in the west to Xinjiang and Tibet in the east to map invasion routes, procure allies among the warring local factions, and train proxies in the art of modern warfare. In Britain’s case, this led to two ill-fated invasions of Afghanistan, across whose Wakhan Corridor the two empires, originally separated by over a thousand miles, almost touched.

This epic struggle came to an end in 1907, as both parties recognized Germany to be the greater threat, but the definitive account is Peter Hopkirk’s The Great Game, published some eighty years later. It was the 1980s, the Soviets had occupied Afghanistan, the Americans (and others) were supplying the mujahideen, and the Great Game 2.0 seemed to have started in earnest. My mother, for one, felt as though she were stepping right into the pages of Kim, her favorite book as a young girl, when in 1988 she followed friendly mujahideen across the mountains above the Khyber Pass. It had been Kipling who first introduced her—a New Yorker with European parents—to Tibet, Nepal, and Afghanistan, and gave her the longing for adventure that ultimately led her to become a foreign correspondent. And now, for her first story on foreign soil, she was sneaking into Kabul, to spy on the Russians!

A similar sense of history doubling back on itself invests Sheila Miyoshi Jager’s The Other Great Game, published this year but obviously the fruit of at least a decade of research. Jager’s subject is Northeast Asia, from roughly 1860 to 1910, and in particular the competition among China, Russia, and Japan over the control of Korea, with Britain and America in supporting roles. It is a story very much the equal of Hopkirk’s in terms of suspense, high stakes, and sheer intrigue, and one that has as grave implications for the geopolitics of this decade as its namesake had for the geopolitics of the 1980s.

The signal events in the story deserve to be retold in brief.

In 1860, the Qing Empire handed the Russian Empire 350,000 square miles of territory, a deep water harbor in the Pacific Ocean, and a border with Korea.

Japan was first to take the alarm. Korea was a vassal of the Qing Empire, though one that had historically preserved maximum autonomy and isolation (outside of the payment of tribute). The Qing Empire was in no position to protect it from expanding Russia. Russian Korea could spell doom for Japan, squeezed between her and the other European Empires to the south and east. Japanese Korea could set the island nation on its path towards parity with the West, securing the mainland, augmenting the natural resources and labor at its disposal, and providing it with a stage upon which to prove the moral quality and administrative capacity of Japanese civilization.

The Qing Empire, for its part—at this point already the Sick Man of Asia—recognized the Russian threat, and its own inability to protect Korea singlehandedly. Thus it co-sponsored the opening of Korea to Japanese commercial and diplomatic ties. Japan would counterbalance Russia, or so the Qing thought. But the influence of these two outside powers on Korea soon led to internal strife. The traditional Qing and the modernizing Meiji had different visions of and interests in Korea; the Korean public was divided; civil war broke out, and quickly broadened into the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95, which ended in victory for Japan.

Until this point, Russia and Britain had been mostly distracted by the original Great Game. Now they took sides in earnest. In the ”Triple Intervention,” Russia intervened to deprive Japan of the most valuable concession it had won in the war—the Liaodong Peninsula with its well-fortified Port Arthur. For this good service, the Qing Empire awarded her the right to build a branch of the trans-Siberian railroad through Manchuria. The need to protect this railroad during the Boxer Rebellion soon morphed into a de facto Russian annexation of the entire region, and Russian influence in the Korean court grew steadily, nursed by resentment of the Japanese. Meanwhile, Britain moved closer to Japan, promising that if she were to go to war with Russia and win, Britain would prevent another ”Triple Intervention.”

In 1903, Russia, for the second time, postponed its withdrawal from Manchuria, and Russian soldiers were discovered in northern Korea, pursuant to a secret lumber concession dating back to 1898. Japan defeated Russia in the 1904–5 Russo-Japanese War, and in 1910 officially annexed Korea, which would remain a Japanese colony until 1945.

Throughout this saga, Jager shows how much Korea dominated the foreign policy and even the internal politics of the countries surrounding her. In the first stage of the long, painful birth of modern East Asia—the rise of Meiji Japan and her reprisal of the European imperial role—the Korean question was ever paramount. It is not for nothing that all three of Japan’s invasions of Manchuria—in 1894, 1905, and 1931—began on the peninsula.

As China grows more aggressive, South Korea and Japan seek to bolster their own capabilities in order to resist her pressure, both by cooperating more closely with the United States and by investing directly into their means of defense.

Jager also draws attention to the ways in which the first stage of East Asia’s modernization sowed the seeds of the second. I was surprised to learn, for instance, that the proposal to divide Korea along the 38th parallel was first put forward by Japan in the lead-up to the Russo-Japanese War. In other cases, her achievement is more of emphasis than of discovery, as when she reminds us that Japan gained Taiwan in the pursuit of Korea, just as the United States later pledged her protection of Taiwan in the same breath as her assistance to South Korea.

Finally, Jager rightly emphasizes the extraordinary toll that the Other Great Game took on the Korean population, in halting development, the indignity of subjugation, and the sheer, bloody loss of life.

This brings us to the unnerving prospect that Jager’s book calls up before us today, as China and the U.S.-led China Containment Coalition seem more and more likely to go to war: The Other Other Great Game.

The Korean peninsula has not moved, and remains the obvious second theater into which a war over Taiwan would spill.

First, there are the American troops and equipment stationed in South Korea, which China would seek to destroy before they can come to Taiwan’s defense.

But that is just the beginning. Seoul is equidistant between Beijing and Tokyo, between the industrial and military bases of Japan and those of northeastern China. The Korean coasts lie on the Yellow Sea, the East China Sea, and the Sea of Japan. From the peninsula, either side could restrict the movements of the other’s navy considerably, launch many more attacks on planes and ammunition stockpiles, and cripple their adversary’s ability to repair or replace the systems and weapons damaged and destroyed in the course of the fighting.

Moreover, since the easiest place from which to attack South Korea is North Korea, it is hard to imagine its vigorous use in the war not bringing about a peninsula-wide conflict. This in turn raises the prospect of a severe border crisis or even of the opening of a second front on the 840-mile-long China-North Korea border, an additional incentive to both sides to take the war to North Korea first.

Or so we would expect, were it not that North Korea possesses nuclear weapons.

And that is, oddly, the ultimate lesson of Jager’s book, a lesson that should probably never sit easy with us: that of the pacifist effect of nuclear weapons.

To be sure, the short-term effect of North Korea’s nuclear weapons is to escalate tensions in Northeast Asia. As China grows more aggressive, South Korea and Japan seek to bolster their own capabilities in order to resist her pressure, both by cooperating more closely with the United States and by investing directly into their means of defense. This gives North Korea reason—or cover—to expand and showcase her military capabilities, both to deter the two democracies and to guard her independence from China. This in turn gives South Korea and Japan reason—or cover—to expand and showcase their military capabilities, which no law of nature prevents them from using against China.

In the long term, however, these nuclear weapons threaten a loss of life so great and sudden, and forebode conditions so unpredictable, that both China and the China Containment Coalition would rather keep such conflict as might spread to South Korea within strict limits, limits that prevent the emergence of a peninsula-wide war.

It is the classic nuclear tradeoff. In exchange for a very small probability of many millions dying by nuclear weapons, one gives up the much larger probability of many hundreds of thousands dying by conventional arms. And if you doubt that the numbers would run that high, then consider just this: the Koreas together are six times as densely populated as Ukraine.