In The Courier , two very different men become friends because they aim to save civilization and embody it.

The Write Stuff?

There is something elegiac in Duncan White’s Cold Warriors, originally published in summer 2019 but released in paperback this past August. The book, a “group biography” of over a dozen literary figures who were involved on one side or other of the Cold War, tells a story that seems almost fantastic today—of a world in which government strategy involved novels, poetry, and literary criticism because literature was a cultural force in a way that it is not today.

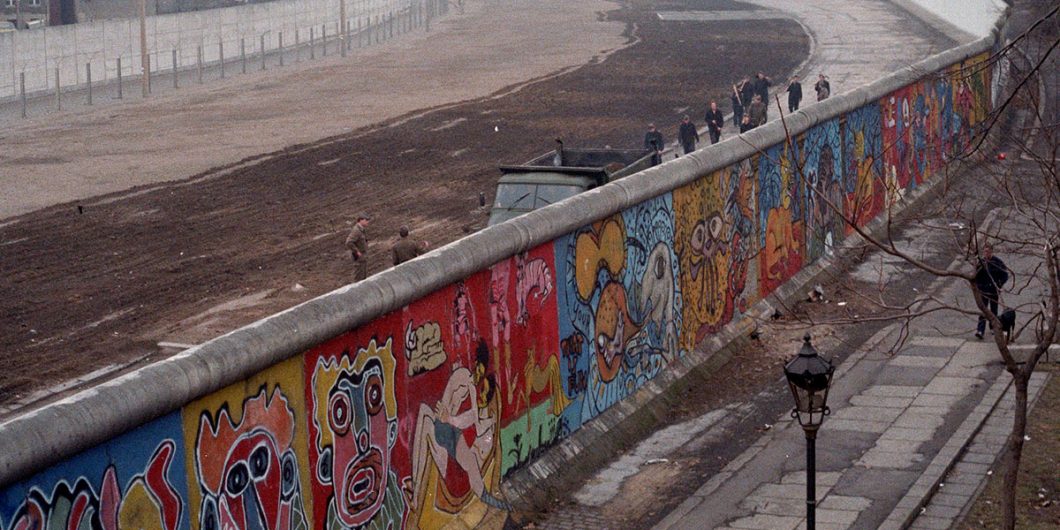

White, a Brit whose doctorate at Oxford (undergrad Cambridge) was on Nabokov and who crossed the pond to add teaching at Harvard to his resumé while still keeping up with ye olde sceptered isle by reviewing books for the Telegraph, begins his tale of the literary side of the Cold War by recounting a CIA mission that took place between February and May 1955 in which ten foot balloons with a rather unique weapons payload were launched from West Germany into Poland. “At the height of the Cold war,” White intones, “the CIA made copies of George Orwell’s Animal Farm rain down from the Communist sky.” White admits that it is an open question as to “how effective literature was in winning over hearts and minds,” but the “indisputable” fact is that “both superpowers” took it absolutely seriously and spent goodly amounts of treasure on getting the right (or left) books published and into the hands of the people while keeping the wrong books out of their hands.

In the latter task, the Soviet Union was much more eager and much more effective—and more willing to spend blood. The poet Anna Ahkhmatova, parts of whose story appears here, said that “not a single piece of literature” was ever allowed to leave the printers under Uncle Joe Stalin. Not surprising given the Party line expressed by the Union of Soviet Writers secretary Zhdanov, who thought that what made Soviet literature “the most advanced literature in the world” was that it did not and could not have “other interests besides the interests of the people, the interests of the state.” Akhmatova’s poetry, forbidden for many years, had the gall to treat topics such as sex and God, which might have interested the people but definitely not the state.

Communism and the Writing Life

White’s volume is nearly 700 pages of text and another 50 or so of notes, but it reads fairly briskly. White knows how to tell an exciting tale and has an eye for the catchy quote (Khruschev: “Berlin is the testicles of the West. Every time I want to make the West scream, I squeeze on Berlin”). Organized into eight parts, beginning with the struggles of Orwell, Arthur Koestler, and others during the Spanish Civil War, it clips along with sections on the show trials of the 1930s, World War II, the post-war activities of writers after the Iron Curtain had been drawn, the third world conflicts in which the superpowers used proxies to gain influence, the movements for human rights in Russia and then-Czechoslovakia, and finally the end of the Cold War with its bittersweet denouement of a parody of democratic capitalism in Russia before Putin stepped in with an authoritative and often authoritarian hand. Each chapter is named after the author or authors it treats, with a subtitle of the place or places and the times it treats, e.g. “Spender: Cadiz, Valencia, Madrid & Albacete, 1937.” Given that the chapters alternate among different figures, one doesn’t get to follow the history of any given figure straight through, which is annoying at first, but given the length of the book, allows the reader to stay interested if one set of figures is not as intriguing (like the bus, another will come along in a few pages) and builds up anticipation of how the stories of one person or group will be connected to another later on.

White seems alternately fascinated and horrified by the idea that the CIA would be funding culture in this way despite there being little evidence that the CIA dictated any terms to the journals it funded.

Though called a “group biography,” Cold Warriors is really more of a literary history of the Cold War that occasionally becomes just a history of the Cold War with a focus on a select group of literary folks involved. Along with Orwell, Koestler, and Spender, we follow parts of the stories of: Mary McCarthy and much of the Partisan Review crowd; the Russian writers Isaac Babel, Boris Pasternak, and Anna Akhmatova; American commie writer of Spartacus (both the novel and film) Howard Fast and former commie Richard Wright; MI6 agents/cynical novelists Graham Greene and David Cornwell (nom de plume:John le Carré); actual British double-agent and “Third Man” Kim Philby; Sandinista poet Gioconda Belli; and the great eastern European dissident writers Andrei Sinyavski and Yuli Daniel, as well as the more famous Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Vaclav Havel. Plenty of other figures walk across the page in passing or in sections. We see Roald Dahl monitoring Vice President Henry Wallace for the Brits and Oxford don and mystery writer J. C. Masterman creating “plausible fictions” for Britain’s double agents. We also see James Jesus Angleton, Melvin Lasky, Irving Kristol, Nöel Coward, and Isaiah Berlin, among others, in cameos. The main set of figures is interesting enough, but apart from Solzhenitsyn, none of them represented a truly conservative voice. Apart from Solzhenitsyn and Greene, none of them represent a religious voice—and the latter’s own faith, especially during the Cold War, was a bit weird to say the least with its calls for Communist-Catholic alliance. Though he treats James Burnham briefly and mentions Whittaker Chambers once or twice, White never even name-checks William F. Buckley or John Paul II—or a great many other literary, political, and religious figures.

Authority and Horror

There are two reasons for this selection. The first is that the literary and critical work promoted by the CIA and various western governments was primarily that of moderate liberals since the (fairly sensible) notion of those promoting the literary Cold War was that it was better to attack from a moderately liberal position than a conservative one. Encounter, one of the most famous of the CIA-sponsored journals around the world, may have spiked some articles lauding Castro but it was no National Review. Stephen Spender, who later professed surprise that he was co-editing a CIA-financed publication, was able to fool himself or be fooled in large part because the journal was publishing interesting articles from a wide variety of political points of view. White seems alternately fascinated and horrified by the idea that the CIA would be funding culture in this way despite there being little evidence that the CIA dictated any terms to the journals it funded. The horror comes in large part from the second reason.

The second reason for the selection is that White himself seems to be a rather conventional liberal who generally accepts, among other things, that the “leftward tilt of Roosevelt’s New Deal” is what improved the American economy during the Depression, that Chambers was right but also “duplicitous and sleazy” (no explanation or examples), and that providing any government agency with lists of potential Soviet spies or sympathizers in the literary world, as Orwell did, is “complicity” different only in degree from Soviet writers denouncing their fellow writers to the NKVD. Or so I gather. White periodically makes a big deal of complicity as a problem, but there is little clarity. He seems bothered that conservatives and the American government were eager to put Orwell’s literature in the hands of readers without also hawking Orwell’s eccentric ideal of democratic socialism.

White is no philosopher, and his attempts at analysis are sometimes a bit confused, as in his discussion of various left-wing writers, such as Gioconda Belli, who discovered that Daniel Ortega and his brother were advocating “aggressive military action to provoke responses from Somoza as a way to keep the country polarized” and also a popular front policy of joining with any group, even anti-Communists, opposed to Somoza. White writes that she “worried that the means no longer justified the ends.” Presumably Belli’s problem was that she suspected the Ortegas had different ends in mind than she did because of the aforementioned actions which led to both more violence and less clarity about what the Revolution was supposed to accomplish, apart from putting Ortega in power. In any case, White reverses the moral principle that “the ends do not justify the means.” Even if utilitarians might argue that a given end justifies the means, no one argues that means justify ends.

Belli’s story ends with her getting out of the revolution-and-government business altogether when Ortega was dissatisfied with her work for the Sandinista’s electoral campaign after he allowed elections in 1989. Like many of the writers in this book, she had romantic ideas of a “new kind of socialism—Nicaraguan, libertarian.” That they were dashed is not surprising in hindsight, though White seems to excuse the Sandinista turn toward power-consolidation as a response to pressure from Ronald Reagan. But White is actually pretty honest throughout the book about the naiveté of the various writers who discovered to their horror that the supposedly independent national communist or socialist movements they were involved with were being directed covertly or openly by the Soviet Union. Or that the Soviet Union was not actually averse to teaming up with the Nazis and had no real freedom for writers to pursue art. Or that third-world regimes headed by supposedly benevolent socialist despots were pretty awful. The tale of Richard Wright’s journeys in Asia and Africa are amusing for the realization that despite having dark skin, the secular liberal novelist had little in common with the people from the mother continent.

Sordid Histories

Many of those profiled were not just gullible but very disturbing people. Unlike with Chambers, White provides plenty of evidence of Koestler’s duplicity, sleaze, and even sexual violence (here, rape) amidst courageous public opposition to totalitarianism. He quotes Cyril Connolly on Koestler: “Like everyone who talks of ethics all day long, one could not trust him half an hour with one’s wife, one’s best friend, one’s manuscripts or one’s wine merchant—he’d lose them all. He burns with the envious paranoiac hunger of the Central European ant-heap, he despises everybody and can’t conceal the fact when he’s drunk, yet I believe he is probably one of the most powerful forces for good in the country.” So it goes with a number of other figures. As with shading the book into straight cloak-and-dagger history, White occasionally shades it into lifestyles of the dissident and debauched. Yet the disturbing personal lives match the public behavior of those such as Mary McCarthy, whose flashes of insight and analytic skill—she saw through the 1930s Moscow show trials and demanded answers concerning disappeared writers—were uneven. Her attempts to hurt the United States in Vietnam really did damage to POWs whom she naively depicted as deplorable rubes when the empty eyes she saw were not the result of stupidity but of living under constant threat of torture.

Whatever the difficulties of the various writers, the book ends on a high note with the accounts of the Eastern Europeans and their heroic struggles to spread the good words and speak truth to power. Unlike other sections, White’s treatment of these figures is somewhat light on their actual words (he also calls Solzhenitsyn’s famous manifesto “Live Not by a Lie”). He favors the dramatic aspects of their public work and occasionally their private lives, but notes that one of the great divides is over whether they should fight with their art or their political action. Orwell ended up deciding in favor of art; Solzhenitsyn always favored art but recognized the need for both. What is inspiring in the telling of the fights of the 1970s and 1980s is how often writers would defend dissident writers even if they did not like them and publishers would work hard to publish their heretical works.

The aftermath of the Cold War is depicted as an anticlimax. White cites approvingly le Carré’s character George Smiley that the right people lost the Cold War but the wrong people won it. I doubt we fully agree on what this means. Le Carré was dissatisfied with the role of global corporations, the gangsterism in post-Soviet Russia, and the excesses of the “War on Terror” in the U.S. But he ended up demonizing “nationalism” in general both in Russia as well as Britain and the United States. Brexit and Donald Trump were symbols to him of all that was wrong in the post-war world. In a 2017 interview, he summarized his generic ideals as “a notion of individual freedom, inclusiveness, and tolerance.” Yet those are the thin reeds that the secular liberal internationalists who won the day preach—and we see how apart from a thicker understanding of human beings they end up being distorted or even thrown out. The sterility of a secularizing West meant the seeking out of other religions, secular and otherwise. Those other religions have jealous gods, too.

The scholar of French literature Bruno Chaouat has noted in a recent issue of First Things that we are in thrall to a new Zhdanovism in which the Americans are joining in. The new dogmas are antiracism and not speaking ill of the Chinese government, from whence cometh our worldwide market, but the results are going in the same direction. We are not yet at the bullet-to-the-neck phase, but like the Soviet Union in the 1930s and 1940s the writers and publishers are anxious to show they are on the “right [left] side of history.” White doesn’t allude to any of the parallels to today’s Western climate—the problems are apparently all in Putin’s Russia and elsewhere. To do so might disturb his colleagues at Harvard, not to mention publishers who might think him conservative. But the reader who is aware that there is more to the story that he tells and more to be learned about our own situation today will find this a gripping, enjoyable, and useful account.