Therapy Notes for a Borderless Culture

During my deployments as an infantryman in Iraq, I would often purchase bootlegged DVDs from a little shop on base owned and operated by local nationals. Occasionally, very rarely, I would even have time to watch them. The few I actually had the downtime to see while recovering from an injury or waiting between missions struck me as enigmatic and unique. The Wrestler ended with Mickey Rourke’s character in the hospital, leaving you to decide whether or not he went against his girlfriend and doctor’s wishes and had his final bout with his arch-rival The Ayatollah. District 9 left the language of the aliens indecipherable—no subtitles, nothing—leaving the audience to infer from context what the aliens were saying. Or how The Mysteries of Pittsburgh was subtly haunted by some strange insinuation of lust which never came to fruition. They were beautiful films which served as a counterpoint to much of the monotony of deployment. Subtlety amid garishness. Complexity amid the mind-numbing simplicity of violence.

Of course, that’s not how any of the films actually are. Imagine my surprise when discussing the movies with friends and family later on I find out that The Wrestler goes on past the hospital scene, actually showing the final match. Or that the language of the aliens in District 9 actually is subtitled. And the erotic insinuation of The Mysteries of Pittsburgh is, in the official theatrical cut, quite explicit. I had of course been watching censored DVDs, tailored to avoid any of the controversial topics which might upset average Iraqi viewers. “The Ayatollah,” non-human entities having the gift of speech, and gay sex were non-starters. In the modern West we’re supposed to feel a revulsion towards censorship, and yet I found the Sharia-compliant versions of the films, not necessarily morally, but aesthetically superior. The official versions seemed to show too much. And they suffered for it. Without being punctuated by their former silences, I found the films to be almost vulgar. Those silences communicated more than the additional footage of the originals. It wasn’t until years later, on reading the philosopher Byung-Chul Han, that I found an explanation of why, in terms of culture and art, less is often more.

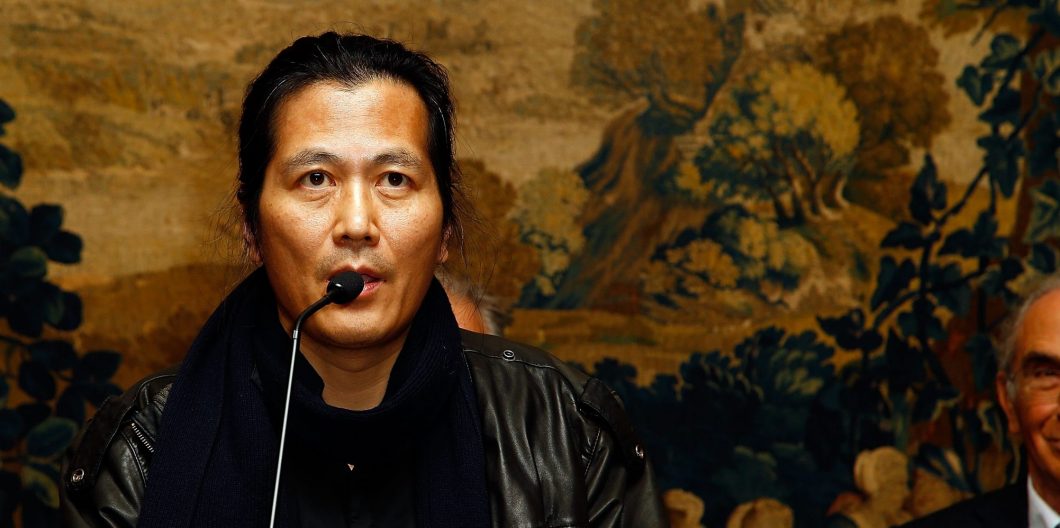

Byung-Chul Han is a Korean-born German philosopher who teaches at the University of the Arts (UdK) in Berlin. He has the reputation of being a bit of an eccentric who rarely answers emails and lectures to packed auditoriums. He hasn’t necessarily achieved the same level of public notoriety as someone such as Slavoj Zizek or Camille Paglia, but he’s known outside of academia. I first learned about him myself in a curious but ultimately disparaging Guardian article about Germany’s “Romantic literary revival”:

Germany’s new Romantics have found their intellectual lodestar in the Korean-born philosopher Byung-Chul Han… Han has championed the Romantic cult of the broken heart as a symbol of resistance against what he sees as a modern cult of ‘smoothness’, spanning iPhone design via Brazilian waxing to the ‘Teflon chancellor’ Merkel.

Of course, included in this “cult of smoothness” which Han critiques is the regimen of the entirely self-created and borderless modern identity. His work takes from both experience and theory that human nature is something broad but fixed. We have a telos, and therefore clearly defined strategies for being at home in the world.

Han’s latest work to be translated into English is The Disappearance of Rituals. His previous books all circled the same subject of being at home in the world, but took various angles of approach: time, eros, technology, disease, and art chief among them. His most recent book focuses on rituals, of course, but the general concerns are no different than his other books. As Han wrote in, The Burnout Society, “Nietzsche already observed that, after the death of God, health rose to divine status. If a horizon of meaning extended beyond bare life, the cult of health would not be able to achieve this degree of absoluteness.” And this is really the gist of it. Han believes that we live in a society which has bestowed “divine status” on things which can’t carry the weight. Part of that process also consists of a grand delimiting. The very notion of narcissism which Han accuses our contemporary world of cultivating is rooted in a confusion of boundaries. For the sake of certain modes of production, Han argues, the borders between self and world are made porous. And since there are no clear delineations, people are forced to navigate a perpetually unstable reality. The smoothness Han bucks against is the direct result the removal of limits and forms through which we experience the fullness of human life. Ritual is chief among these formal experiences. Rituals give us a respite from the modern compulsion to constantly produce ourselves anew through each shifting moment. Rituals, as Han writes, “de-psychologize” us, granting us a respite from the narcissism of a boundaryless world.

The Disappearance of Ritual begins by describing the relationship between ritual and time. Han writes that “We can define rituals as symbolic techniques of making oneself at home in the world. They transform the being-in-the-world into a being-at-home. They turn the world into a reliable place. They are to time what a home is to space: they render time habitable. They even make it accessible, like a house.” We can’t have a sense of duration without the ability to linger on things. We can’t cultivate attention or thought without being able to tarry. When Han writes about the durability which ritual creates, the lingering which “…presupposes that things endure.” I’m reminded of the Spanish novelist Javier Marias justifying his discursive prose style by explaining that time needs time in order to become itself.

So when ritual, a word often preceded by “empty” in contemporary parlance, disappears, where does the time go? Han explains that “Today, time lacks a solid structure. It is not a house but an erratic stream. It disintegrates into a mere sequence of point-like presences; it rushes off. There is nothing to provide time with any hold [Halt]. Time that rushes off is not habitable.” In other words, time doesn’t simply stop moving in its familiar ambulations, but becomes something else entirely: accumulation. A pointillist landscape of independent and unconnected moments, piling up haphazardly. A life measured out, not in coffee spoons, but clicks, likes, Tweets, and freshly minted identities.

With the phrase “the production of meaning” Han connects popular fiction with porn with Twitter with drone wars with political correctness. What they each share in common is that they rely on an ethos of consumption and accumulation.

The loss of a ritualistic sense of time is at root a loss of symbolic perception. Symbols are the things which bind us to a reality outside of ourselves. Han explains that “Symbol (Greek: symbolon) originally referred to the sign of recognition between guest-friends (tessera hospitalis). One guest-friend broke a clay tablet in two, kept one half for himself and gave the other half to another as a sign of guest-friendship. Thus, a symbol serves the purpose of recognition. This recognition is a particular form of repetition…” And repetition is a vital element of ritual. There can be no recognition without repetition and vice versa. Within the symbolic logic of the ritual, we recognize more than simply the experience of “duration” itself, but through that experience intimate permanency. Han writes that

Symbolic perception, as recognition, is a perception of the permanent: the world is shorn of its contingency and acquires durability. Today, the world is symbol-poor. Data and information do not possess symbolic force and so do not allow for recognition. Those images and metaphors which found meaning and community, and stabilize life, are lost in symbolic emptiness. The experience of duration diminishes, and contingency dramatically proliferates.

If we’ve lost symbolic perception, what exists in its place? Han explains that “Symbolic perception is gradually being replaced by a serial perception that is incapable of producing the experience of duration.” There are echoes in this (unintentional, I’m sure) of Walker Percy’s idea of the symbol as something which binds us together in mutual perception as opposed to a sign, which merely suggests a one-to-one referent and elicits something which Han calls “serial perception.” Serial perception, the constant registering of the new, does not linger. Rather, “it rushes from one piece of information to the next, from one experience to the next, from one sensation to the next, without ever coming to closure. Watching film series is so popular today because they conform to the habit of serial perception. At the level of media consumption, this habit leads to binge watching, to comatose viewing.”

This degeneration of experience, which accompanies the loss of symbolic perception, inspires the names of the last few chapters of Han’s book “From Dueling to Drone Wars.” “From Myth to Dataism.” “From Seduction to Porn.” And it’s here, in the final chapter of the book, that Han describes my own vague sense of loss in watching the unedited versions of the films I first saw in Iraq. The passage is worth quoting in full:

Porn is a phenomenon of transparency. The age of pornography is the age of unambiguousness. Today, we no longer have a sense for phenomena such as secrets or riddles. Ambiguities or ambivalences cause us discomfort. Because of their ambiguity, jokes are also frowned upon. Seduction requires the negativity of the secret. The positivity of the unambiguous only allows for sequential processes. Even reading is acquiring a pornographic form. The pleasure of reading a text resembles that of watching a striptease. It derives from a progressive unveiling of truth as though it were a sexual organ [der Wahrheit als Geschlecht]. We rarely read poems any more. Unlike popular crime novels, they do not contain a final truth. Poems play with fuzzy edges. They do not admit of pornographic reading; they do not possess pornographic sharpness. They resist the production of meaning.

With the phrase “the production of meaning” Han connects popular fiction with porn with Twitter with drone wars with political correctness. What they each share in common is that they rely on an ethos of consumption and accumulation. It’s much more difficult to monetize seduction than porn. It’s far easier to acquire data than wisdom. Poetry resists consumption as easily as Twitter encourages it.

Han is a joy to read. His writing isn’t quite aphoristic, but it has an Hemingway-esque sinewy strength to it. His pronouncements hit you at a gut level. In part, this is because Han writes about real life as it’s actually lived by people. But his style reflects the concrete nature of his concerns. It reminds you less of typical philosophical writing—the dialogue or jargon-laden tract—and more like therapy notes for a sick culture. Han doesn’t so much defend his ideas as present them as made objects for us to consider in the light of our own experiences. This strength is, as all strengths, a weakness as well. Han often asks the reader to be sensitive to his own lived experience in order to begin to understand his arguments. This sensitivity is required to comprehend the full heft of Han’s work. It’s a demand, but not an unfair one. If an enlisted grunt in the Diyala Province can intuit a sense of the cultural loss Han critiques, the average reader is probably alive to it in their own experiences as well.