If Hazony's traditions are just accidents of cultural evolution or history, then we’re back to full blown relativism.

Traditionalizing Everything

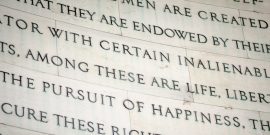

History and tradition are having a moment in American constitutional law. In recent landmark cases, the Supreme Court has looked to history and tradition as guides to construing the meaning of the Constitution. For example, in Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, the justices ruled that the Establishment Clause “must be interpreted by ‘reference to historical practices and understandings.’” Practices consistent with American tradition, like the non-coercive prayers a public school football coach offered in Kennedy, do not violate the Clause. Similarly, in the Dobbs case that held that the Constitution does not confer a right to abortion, the justices maintained that an “unbroken tradition of prohibiting abortion” had existed in the United States right up until Roe v. Wade in 1973. One could give other examples of the Roberts Court’s use of history and tradition, in areas like gun rights, trial procedure, and federal jurisdiction.

The Court is working out exactly what the history-and-tradition test entails and there are many questions. Jack Balkin’s new book, Memory and Authority: The Uses of History in Constitutional Interpretation, thus comes at an opportune time. Balkin, the Knight Professor of Constitutional Law and the First Amendment at Yale Law School, has two goals: first, to describe how lawyers and judges use history and tradition in practice and, second, to argue how lawyers and judges should use them. In the first, he succeeds; in the second, not so much. Balkin correctly observes that what we call tradition is often constructed and contested, a matter of judgment on which people differ. His understanding of tradition is at times so expansive, though, that one wonders whether he is talking about tradition at all.

Memory and Authority begins with a description of “what is actually going on when people use history to make constitutional arguments.” By “people,” here, Balkin means mostly lawyers and judges, as opposed to law professors. Unlike law professors, who make their careers by developing grand theories that resolve questions at an abstract level—and drawing sometimes arcane distinctions between their own theories and others’—lawyers and judges work in the real world. Lawyers, in particular, have clients who want to win cases. Lawyers therefore value flexibility over consistency and make whatever arguments seem most likely to persuade a court to rule in their favor.

In practice, lawyers employ constitutional history in a variety of ways. A “skillful advocate,” Balkin writes, offers a court both “positive precedents to be followed and negative historical examples to disown.” Lawyers mine history selectively; they “pick the part of the past they want to honor, while disclaiming or glossing over other parts of the past.” And their opponents, “eager to rebut them,” do the same. Opposing counsel “try to flip the script, seizing on omissions and complications.”

Balkin is correct about all this. He is also correct that the most persuasive historical arguments in practice rely, sometimes implicitly, on the sense that they promote positive present-day results. Good lawyers know that if you want to persuade a court to adopt a particular reading of a legal text, you should show both that the reading is formally correct and that it has beneficial social consequences. After all, most judges don’t want to cause social harm and will feel more comfortable ruling in ways they think promote public welfare. Balkin criticizes what he calls “thick” originalism for missing this point, but that criticism is unfair. (I will not discuss here Balkin’s distinction between “thick” originalism and his own “thin” or “living” originalism, which has been covered elsewhere.) Most originalists support originalism because it restrains judges and allows democracy, including the constitutional amendment process, to function better than non-originalist theories of constitutional law. These are justifications based on social consequences.

Balkin’s normative argument about the proper role of tradition in constitutional law is less persuasive, though. He prefers the terms “collective memory” and “usable past,” which reflect his conviction that tradition is constructed by actors in the present, who cull history for practices and beliefs that serve edifying purposes today. A “unitary tradition” does not exist. There are only competing traditions, which recommend themselves to us because they correspond to values and commitments we find worthy now. “One must shape the diverse and conflicting elements of the past,” he writes, “into something that can have normative authority for us today.” Tradition thus can promote progressive as well as conservative results, and progressives should not cede tradition to their opponents. “If people refuse to claim memory and tradition for themselves,” he warns, “they will be governed by other people’s versions.”

Balkin’s own understanding of collective “constitutional memory” is so expansive that at times it hardly seems like tradition at all.

Moreover, he writes, arguments from historical practice appeal in the first place only to people who feel connected to the community in which those practices are embedded: “They assume that both the speaker and the audience identify with a common tradition, that the identities of both speaker and audience are partly constituted by that tradition, and therefore that both speaker and audience wish to continue to be true to it.” In contemporary America, significant numbers of people do not identify with what one might call the mainstream legal tradition which, they believe, denigrates and excludes them. Balkin argues that the Court should widen its search for historical sources beyond the Framers—all white men, many slaveholders—to include the perspectives of subordinated groups.

These observations are sound, too, as far as they go. But there are limits to how elastic tradition can be, and Balkin’s own understanding of collective “constitutional memory” is so expansive that at times it hardly seems like tradition at all. For example, he praises Obergefell v. Hodges, which held that the Constitution confers a right to same-sex marriage, for its correct use of tradition. True, there is no “history of specific legal guarantees for same-sex marriage in American law.” But he argues that American tradition should be understood in a broader, more sensitive way, as a commitment to animating principles. The Obergefell Court correctly saw that the reasons why Americans historically have supported marriage generally obtained in the new context of same-sex marriage as well, and applied those reasons to reach a satisfactory present-day result. One can “alter or even reject existing practices,” he writes, “while being faithful to the country’s traditions of liberty.”

Now, one can praise or criticize the Court’s reasoning in Obergefell. But to paraphrase something Grant Gilmore said about Oliver Wendell Holmes in a different context, the magician who can traditionalize Obergefell can, the need arising, traditionalize anything. Tradition refers to concrete practices and accommodations that endure across time in a community, not abstractions like “liberty” or “equality” or “dignity” or “justice.” And one cannot plausibly claim that same-sex marriage is an American tradition in that sense. One must choose which traditions to follow and which to discard; that is the essence of modernity. But one cannot decide a case according to an abstract, indeterminate principle and call oneself a traditionalist. One may as well say that one is doing something new—that one is deciding a case based on one’s normative commitments and leave it at that.

Memory and Authority encourages lawyers who have sympathy for the role of tradition in law to own up to the fact that they inevitably must pick and choose among the traditions that make up our legal heritage and to account for the objections of their fellow Americans who do not have the positive feelings about the past that they do. In that, the book is very valuable. In terms of constructing a persuasive argument for the use of tradition in law, though, the book does not really deliver. Balkin’s “usable past” turns out to be much more about what is “usable” than what is “past,” such that tradition seems to mean whatever broad principle works to get you to your present goal. That may be good or bad, but tradition it’s not.