The Bostonians was a reactionary novel even in the day it was written, and this is exactly why college students should read it.

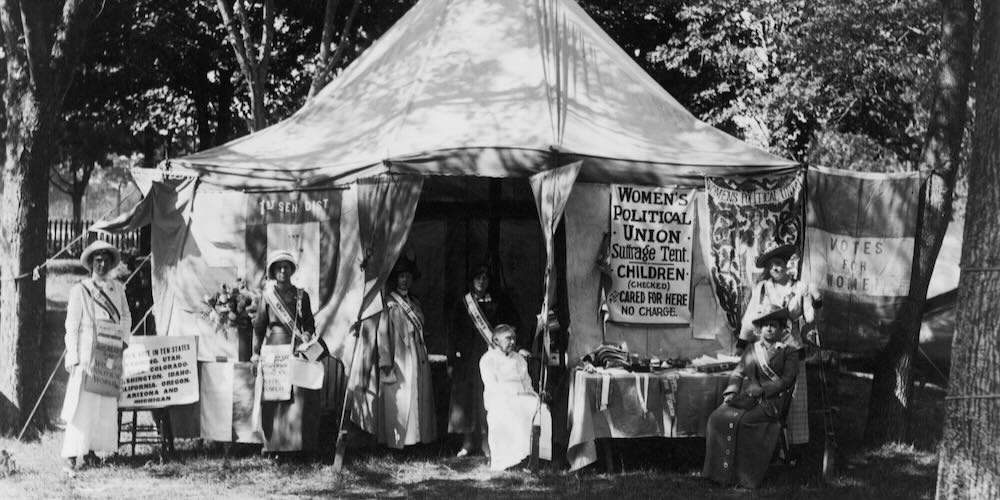

When Feminists Liked Kids

In 1874, two Bostonian women named Bessie Greene and Lilian Freeman Clarke founded an institution for expectant mothers. Known as the Society for Helping Destitute Mothers and Infants (SHDMI), it embraced an approach to charity that was truly American, in a Tocquevillian sense. The SHDMI wanted to help desperate women. But it also placed a high value on both moral responsibility and associational life. Instead of setting up headquarters in a brick-and-mortar establishment, representatives worked with women one-on-one. Some financial help was given, but just as much stress was placed on friendship, general life advice, and help in finding jobs. The goal was to supply some of the social “roots” that were typically missing in the lives of unwed mothers.

The organization seems to have worked quite well for several decades, pulling scores of women out of poverty and helping them to become competent mothers. As Boston moved into the twentieth century, a newfangled network of charities effectively swamped the SHDMI’s old-fashioned methodologies. Social Darwinism and eugenics were in vogue now, and the SHDMI was pressured to have women professionally evaluated, to see whether they were mentally fit for motherhood. By 1912, the organization had largely given up on self-reliance and moral responsibility, and a decade later it had ceased to exist.

It’s a fascinating story, and just one of many episodes related by Monica Klem and Madeleine McDowell in their new book, Pity for Evil, which explores the intersection of first-wave feminism and abortion at the turn of the century. Many contemporary readers are startled to find that the suffragettes were staunchly opposed to abortion, and this reality has even been disputed by some modern feminists. Pity for Evil reviews the very considerable evidence, and illuminates the motivations of the concerned parties, while also exploring charitable efforts to assist pregnant women and abandoned children. For the pro-life movement today, working to chart a path forward, it’s worth appreciating how earlier chapters of this story unfolded, and what the consequences have been.

In our own time, a sweeping anti-feminism is somewhat in vogue on the right, which treats all forms of feminism as fundamentally destructive to the family, authentic femininity, and women’s embrace of the maternal role. Second-wave feminism is treated as a natural and basically organic continuation of earlier feminist ideas, with all feminism understood to be a war against nature and a flight from motherhood, with radical autonomy as the goal. In fact though, the Suffragettes took considerable pains to draw attention to the problem of abortion, which they viewed as the evil fruit of women’s ignorance, moral immaturity, and lack of agency. There was a strong current of “freedom for” in those early feminist conversations that receded into the background in later iterations of feminism. As the early feminists saw it, women needed education, earning power, and a full complement of political rights precisely so they could achieve full moral maturity, enabling them to be better mothers and social contributors.

Revolting Outrages Against the Laws of Nature

In the post-Civil-War era, abortion rates seemed to be rising steeply, as evidenced by the sharp uptick in stillbirths. This trend was widely understood to reflect the growing use of abortifacients, and everyone recognized that many more early abortions were surely happening off the official record. Black market abortionists were increasingly present in all major cities, hawking their services in lightly disguised ads that could be found in most popular publications.

People generally need to be treated like full-fledged adult citizens before they can be expected to grow into that role. Weak, infantilized women may find themselves unequal to life’s harder tasks, such as childbearing.

One publication, at least, refused to take their money. That was The Revolution, owned by Susan B. Anthony and edited by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Parker Pillsbury, and dedicated from the beginning to advancing women’s suffrage and political rights more generally. This newspaper ran regular articles on the evils of “child murder,” and refused to accept ad money from “quack doctors,” readily recognized by the editors as abortionists. Abortion, in the view of this paper, was both a serious wrong in itself and degrading and dangerous to women. This is why The Revolution referred to abortions as, “revolting outrages against the laws of nature.”

Questions of moral responsibility were obviously fraught here. The feminists of this era widely assumed that a virtuous woman would understand the seriousness of maternal responsibility, and be eager to care for her children so far as she was able. For some, that ability did not extend very far. Abortion had become a social problem in part because some women, especially in the wake of the war, were too destitute to support a child, with no reasonable prospects of securing steady employment. The case was especially grim if a poor woman became pregnant out of wedlock, thus incurring the strong social stigma that often made it difficult for unmarried women even to find hospitals willing to deliver their babies. Despite that strong disincentive, poor women often did become pregnant out of wedlock, especially when extreme poverty drove them to prostitution. Others might be impregnated by employers or landlords in quid pro quo arrangements that desperately poor women could not easily escape.

It’s easy to see how this problem led many thinkers into a robust virtue- and responsibility-oriented argument for women’s rights. Abortion, feminists argued, was frequently a foreseeable consequence of women’s lack of skills, earning opportunities, and legal protections. Women faced serious restrictions even on their ability to own or inherit property. These disadvantages left destitute women vulnerable to unscrupulous men, facing the serious responsibilities of motherhood with no realistic way to shoulder the burdens.

Poor women were not, of course, the feminists’ sole focus. Even for women who were not destitute, deficiencies in education arguably made it harder to rise to the challenges of maternity. Health and physiology were one component of the problem, since some women had a poor understanding of reproductive health, and truly did not realize that a child had a heartbeat well before quickening. But there were also questions of moral development, which was facilitated by both education and the responsibilities of citizenship. Wealthy women, as Mary Wollstonecraft observed, could easily become soft and self-indulgent when their responsibilities were largely limited to directing servants, hosting parties, and looking pretty. Working women could become slavish and degraded when they were not given the dignity and duties of citizens, with serious consequences for their children. Both cases illustrated the same point. People generally need to be treated like full-fledged adult citizens before they can be expected to grow into that role. Weak, infantilized women may find themselves unequal to life’s harder tasks, such as childbearing.

First-wave feminists were certainly interested in eroding the double sexual standard that treated unchastity as ruinous in women, but merely unseemly for men. However, accusations of injustice were balanced against calls for virtuous living and an embrace of Christian morality. Women needed political rights and opportunities, not for the sake of unfettered autonomy, but rather so that they could attain moral maturity and fulfill serious obligations in a dignified way. Rising abortion rates were a sign of the gravity of women’s moral and material needs, which could only be adequately met if they were given political rights.

This Lamentable Waste of Human Life

As states and cities crafted responses to the problem of abortion, conversations about moral hazard became heated and fraught. Foundling hospitals (essentially serving as orphanages for newborn infants) were controversial from the start; many feared that they would encourage immorality by enabling unwed parents to escape the consequences of their actions. However, the humanitarian problem eventually became too pressing to ignore. Almshouses were, for a time, the only institutions where abandoned children could be brought, but the great majority died of neglect, and anguish over “this lamentable waste of human life” eventually moved some political bodies, such as the Massachusetts legislature, to allot funds for foundling hospitals. The Massachusetts Infant Asylum had a dramatic impact, insofar as the great majority of infants brought there did survive, with many being placed for adoption, while others were eventually restored to their natural mothers once their financial situation was less desperate. Unwed mothers were sometimes hired here, particularly as wet nurses.

Together with the foundling hospitals, organizations like the SHDMI (mentioned above), helped to support and stabilize destitute mothers. Other reformers focused on improved health education for women; one chapter of Pity for Evil discusses the relatively new phenomenon in the late nineteenth century of female physicians, some of whom dedicated their lives to supporting impoverished mothers and their infants, literally saving many lives.

Eugenicists lost sight completely of the value of the child, which was once such a point of emphasis for anti-abortion feminists. Their desire to relieve poor women of the burdens of pregnancy now dovetailed with the desire to rid the world of “a range of “undesirables.”

Insofar as first-wave feminists did support bodily autonomy for women, they did this primarily by advocating “voluntary motherhood,” which at the time was understood to mean that wives should have unilateral discretion over marital relations. One wonders what the range of opinions one might find among pro-lifers today if this idea were re-introduced. Is it reasonable to ban abortion, but affirm a married woman’s right to deny her husband for months or years at a time if she feels unequal to another pregnancy? In an age of artificial contraceptives, this movement is unlikely to gain much momentum, but the logic of the position is interesting to consider nonetheless. What do spouses owe to one another, given especially the non-reciprocal demands of human reproduction? How do the goods of mutual concern and spousal friendship get weighed against the needs and intrinsic dignity of each individual?

A Degraded, Demoralized, Half-Made-Up Race of Children

If the first-wave feminists were indeed so committed to responsible motherhood, one might ask: what went wrong? Why did feminism abandon this stance and start pressing, with relentless ardor, for women’s absolute bodily autonomy? Klem and McDowell don’t really answer this question, since the relevant developments mostly occurred after the period being examined in the book. Nevertheless, they do allude to one transformative turning point, in the early twentieth century, when the eugenics movement began to exert its influence on feminism and American society more broadly.

Anti-abortion feminists had always advocated sympathy for poor and unwed mothers, as well as a high respect for responsible childbearing. But eugenics pushed beyond the sympathy that late nineteenth-century feminists felt for unwed mothers, moving instead towards indignation at the toll reproductive burdens took on poor women. Shifting away from “voluntary motherhood,” feminists instead embraced a more patronizing and less demanding position. Eugenicists, meanwhile, lost sight completely of the value of the child, which was once such a point of emphasis for anti-abortion feminists. Their desire to relieve poor women of the burdens of pregnancy now dovetailed with the desire to rid the world of “undesirables,” and this line of thinking shaped the paradigm of Margaret Sanger, the fledgling Planned Parenthood, and second-wave feminism. Some, like the editors of Woodhall and Clafin’s Weekly, began as anti-abortion feminists, but ended up railing against those irresponsible mothers who cursed the world with a “degraded, demoralized, half-made-up race of children.” The path from here to a pro-abortion feminism is not hard to discern.

There is an important lesson here that pro-lifers, and cultural reformers of all stripes, should take to heart. There is always a heavy price to be paid for defaulting on serious moral obligations. Human relationships are demanding, and we sometimes find ourselves saddled with obligations that we did not choose and feel unequal to shouldering. Pregnancy can be a particularly severe test in this regard, since the burdens it imposes are heavy, sometimes unexpected, and carried first and foremost on behalf of a person not yet known. Nevertheless, recent history has shown how widespread social decay tends to follow when we refuse to recognize those responsibilities.

Children are demanding. Life is demanding. There is, in the end, no way around this hard truth. Though it often seems that modern people are too soft, decadent, or morally corrupted to accept demanding realities, efforts at persuasion are still richly worth the effort. The pro-life movement, in particular, must work now to rebuild modern people’s appreciation of the close relationship between political rights and serious moral responsibilities. We do not want rights and freedoms simply for the sake of pleasing ourselves. We want them precisely so that we can live for something (or someone) beyond ourselves. Perhaps, alone among their empty pleasures, even desiccated moderns are beginning to see that this is what they really need.