How can the largest items in the federal budget, Social Security and Medicare, be preserved without more borrowing?

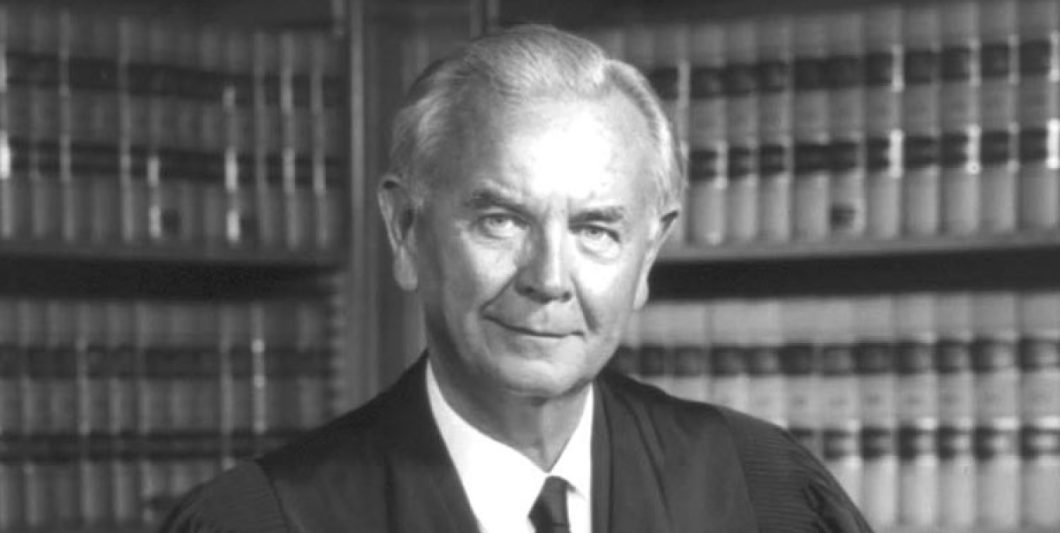

Brennan’s Best or the Court’s Worst?

Goldberg v. Kelly, a landmark Supreme Court decision creating constitutional rights for “new property,” like welfare, turns 50 this month. William Brennan, the leading liberal justice of the 20th century, called it one of his best, if not his best opinion. He described it as “injecting passion into a system whose abstract rationality had led it astray” and “declaring that sterile rationality is no more appropriate for our administrative officials than for our judges.”

Yet Goldberg‘s birthday is not one to celebrate—and not just because Brennan denigrates the formal methods of legal reasoning that are guardrails of the rule of law. The opinion elides the essential distinction between private property and government benefits. Indeed, read with full force, it may suggest that both welfare and private property have the same status: both exist at the sufferance of government. Their only protection, then, are the due process rights the Court chooses to grant. Moreover, the opinion embodies judicial overreach. The Court pretends that it can calibrate the procedures for determining continued eligibility for welfare benefits, although it has no expertise in the subject.

While the decision has been distinguished and cabined, it has never been overruled. Its blurring of the distinction between private property and government benefits could easily gain new energy from some future justices—like those appointed by a socialist, to take a purely hypothetical example!

Goldberg v. Kelly was a challenge under the Due Process Clause to New York’s relatively elaborate process (described more below) for terminating welfare benefits. The most important question was why the Clause applied at all. The Clause reads “No person shall be . . . deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law.” Welfare payments are obviously not life or liberty. Brennan argued instead that they were property. Of course, they are not property in the traditional sense of property that informed the Due Process Clause either at the time of the Framing or the Fourteenth Amendment, the latter of which made the Clause applicable to the states. Welfare consists of payments best understood as a gratuity from the state. They are not property at common law or even rights that resemble common law property rights.

Brennan did not deign to make a full argument that welfare benefits were “property” within the meaning of the Clause. He instead quoted with approval a lower court opinion that said that welfare recipients had “brutal need” for them, as if need created a property interest. With a sleight of hand, he also cited some cases in which the government was alleged, unlike in Goldberg, to have violated independent constitutional rights like those of the First Amendment. But these rights, unlike the Due Process Clause, are not trigged by a property interest and the government might violate them even if the interest does not rise to the level of property.

Most theoretically, Brennan quoted a famous law review article by Yale law professor Charles Reich that embodies the 1960s disregard for tradition, arguing that that society is built not around the rights recognized at common law or specified in the constitution, but around “entitlements.” Reich included within the concept of “entitlements” benefits given by the government, like welfare, and rights that are clearly property at common law, like the right to stock options and private pensions. All entitlements, he argued, deserved procedural protections.

Once that equation between new and old property is made, the opinion’s logic creates a dilemma. If the new property is really property, it would appear that government could not decide to do away with welfare benefits altogether or even lower them, just as it could not appropriate all or a portion of private pensions. Both would be takings. Alternatively, to keep the equation between old and new property without interfering with government’s capacity to modify government benefits, one would have to weaken the protection given to old property, eroding core protections of a civil society.

Also troubling is the opinion’s blithe implication that all our property is an entitlement—ultimately a matter of government creation and sufferance. Modern politicians sometimes make the same kind of argument, as when, in the heat of his 2012 reelection campaign, President Obama incautiously said to a hypothetical entrepreneur, “you didn’t build that.” But it is more disquieting to have this view implied in a deliberated majority opinion of the Supreme Court.

After deciding that welfare was property that triggered the application of the Due Process Clause, Brennan then determined that New York had not provided the process that was due. This part of the opinion showed off another hallmark of his jurisprudence—an unshakeable confidence that the Court was better than the political branches at making social policy.

New York did in fact provide an elaborate process before terminating welfare benefits. A caseworker who suspected that a recipient was no longer eligible for benefits had to meet face to face with him to discuss the matter. If the caseworker continued to think the recipient ineligible and his supervisor concurred, the recipient was sent a letter asking him to tell why he should not be terminated. He or his attorney could provide evidence of his continued eligibility. Only if such evidence were unsatisfactory would he be terminated. In addition, after termination the recipient could get a full trial-type hearing (with cross examination and other such procedures) to contest the termination.

Brennan nevertheless held that New York violated the Due Process Clause. New York was required to hold a full airing of the facts in a proceeding before termination, including cross-examination by a lawyer. Brennan in fact required a pre-termination, trial-type hearing even as he disingenuously said he did not require a form of judicial or quasi-judicial hearing. He offered no empirical evidence that switching the timing of a hearing would substantially improve accuracy, let alone improve it enough to outweigh the costs of paying out welfare benefits that cannot be recovered—costs that are borne by working taxpayers. Indeed, it is not clear that some third alternative might not be best of all, like spot checks of the accuracy of decisions to terminate benefits, with bonuses for caseworkers who get decisions right. Perhaps sensing his lack of empirical support, Brennan also implies that the hearing will promote the dignity of welfare recipients, although only a lawyer could think the route to dignity is cross-examination.

The Supreme Court has no expertise in the efficiency of bureaucratic procedures. Nor is there any reason to think that the political branches in New York struck the wrong balance. After all, New York chose to provide the welfare benefits. Moreover, states have a much better sense of their budget and financial tradeoffs than does the Supreme Court.

But Brennan does not give any deference to New York’s factual judgments about how to shape its procedures, nor does he order any further lower court hearings to take evidence on the question. Brennan famously called Edwin Meese’s defense of originalism “arrogance cloaked as humility.” Brennan’s jurisprudence certainly dispensed with the cloak.