Faith in America’s founding principles, and the integrity of American efforts to promote human rights, has been undermined.

Christian Contributions to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

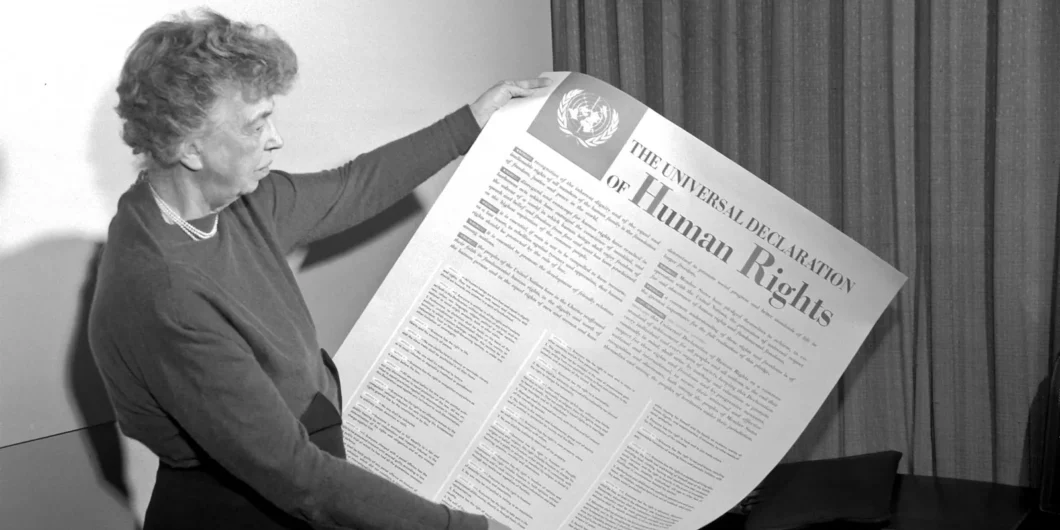

Ratified 75 years ago on December 10, 1948, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) has been, in many ways, a landmark achievement for the modern pursuit of justice. The significance of the UDHR lies not only in its positive contributions to normative frameworks for international political institutions and scholarly discourse. It has also helped catalyze critical evaluation of the larger concept of rights. A number of voices, responding in part directly to the UDHR as well as the broader dominance of “rights talk” in political analysis and social commentary, have questioned the salience of such concepts.

Law professor and former ambassador Mary Ann Glendon has warned about the emphasis on rights at the expense of responsibilities, even as she has also done excellent work to unearth a more robust understanding of rights in the American tradition and the formation of the UDHR itself. French political philosopher Pierre Manent has interrogated the concept of human rights related to and distinct from the natural law. Manent worries that absent an objective understanding of human nature as manifest in social institutions, the rhetoric of rights will “prove damaging when the increasingly exclusive preoccupation with rights in the end obscures the purpose of the institution and undermines its effectiveness.” As part of his larger discussion of rights and critique of the UDHR, moral theologian Nigel Biggar contends, “Rights that are over-specified, so that they are too closely tied to the particular economic and political structures of the history of the West, have no good claim to be natural, universal, applicable always and everywhere.”

The UDHR itself, although it claims and intends to be “universal,” does have its own distinct history and particularity. It arises out of the broader Western tradition that respects individual rights, human dignity, and objective justice. This tradition is in turn formed by a variety of sources, including Jewish and Christian theology, ancient peripatetic philosophical traditions, and Roman law. The summer before the UDHR was ratified, Unesco published a document compiling a wide variety of responses to the proposal to create a global bill of human rights. This text includes an introduction by the French philosopher Jacques Maritain (1882–1973) as well as an appendix on “The Grounds of an International Declaration of Human Rights.” In addition, dozens of scholars, practitioners, politicians, philosophers, and scientists provide responses, some brief and some more lengthy, to a questionnaire and prompt circulated by Unesco. Among the luminaries included in the publication are Mahatma Gandhi, Harold J. Laski, Benedetto Croce, Teilhard de Chardin, and Aldous Huxley.

The purpose of this brief essay is to introduce some of the Christian contributions and contexts of the formation of the UDHR and its legacy, with a special focus on Jacques Maritain and Charles Malik (1906–1987), before concluding with some questions about the ongoing viability of this kind of project as we face an increasingly pluralistic and post-Christian future.

Jacques Maritain (1882–1973)

For many the neo-Thomist philosopher Jacques Maritain is the name most closely connected to the UDHR, even though the text was a committee document and Maritain’s contributions are for the most part indirect. (Paul Marshall has called Maritain “a godfather to the process” that culminated in the UDHR). The author of more than 50 books, including a number of significant texts that treat the concepts of human rights, natural law, and human dignity, Maritain was a fierce proponent for the UDHR. But he as well as anyone recognized the difficulties faced with articulating a doctrine of universal rights that could be assented to by what he called “many schools of thought.”

“It is related that at one of the meetings of a Unesco National commission where Human Rights were being discussed,” writes Maritain, “someone expressed astonishment that certain champions of violently opposed ideologies had agreed on a list of these rights. ‘Yes,’ they said, ’we agree about the rights but on condition no on asks us why.” The basis for such a grounding for rights was precisely where disagreement begins, but Maritain was nevertheless optimistic that at least a practical level of agreement could be reached. Part of this optimism was based on his understanding of the natural law, which was the objective foundation for human nature itself and thereby for any accurate accounting of the rights, duties, and destiny of human beings.

Although Maritain’s own understanding of the natural law was deeply rooted in the Thomistic and broader Roman Catholic tradition, by its own conclusions agreement with the truth of the Catholic faith is not required for affirmation of at least some of the elements that would form a common bill of human rights. The ontology of the human person grounded in a Christian account of creation and preservation was true, as Maritain understood it. But agreement with that ontological account was not necessarily required for assent to some of the practical conclusions or observations that such an ontology entails. “In the field of practical conclusions,” contends Maritain, “agreement on a joint declaration is possible, given an approach pragmatic rather than theoretical and co-operation in the comparison, recasting, and fixing of formulae, to make them acceptable to both parties as points of convergence in practice, however opposed the theoretic viewpoints.”

In this way the distinction between ontology and epistemology as well as a distinction between theoretical and practical reason provide Maritain with some justification for a hope that some level of consensus might be reached by adherents to various faith traditions and members of different cultural groups.

The “universal” modifier in the UDHR was never intended to describe something that would require unanimous affirmation or consent. Instead, the modifier was intended to describe a set of claims or propositions that would apply everywhere, always, and to everyone. The extent to which the UDHR met those aspirations is a different question than whether it has received unanimous or universal assent and still less universal enforcement. It most certainly has not achieved those latter aims.

But, as Maritain also warns us, “we must not expect too much of an International Declaration of Human Rights.” In his own contribution to the Unesco Human Rights volume, Maritain limited the scope of the declaration to “the civilised world,” and reiterated that “for the purposes of that Declaration, practical agreement is possible, but theoretical agreement impossible, between mind and mind.” If the pursuit of justice must always be incremental, partial, and incomplete in this world, then perhaps, at least from Maritain’s perspective, the achievement of a declaration of human rights that is universal in at least some sense is worth celebrating.

To some significant degree the faith that both helped create and maintain the UDHR and the dignified picture of the human person articulated therein is the Christian faith.

Charles Malik (1906–1987)

Charles Habib Malik served as the Lebanese Ambassador to the United States and to the United Nations beginning in 1945 and was appointed Rapporteur of the U.N. Human Rights Commission in 1947 as it was beginning deliberations on the drafting of the UDHR. There were few people as uniquely qualified as Dr. Malik to engage in this work, and probably almost no person had a greater impact on the philosophical (and at points theological) shape of the document itself than he did.

Dr. Malik was born into an Arab Christian family in what is today Beirut, Lebanon, when it was at that time a part of the Ottoman Empire. He studied philosophy at Harvard University and won a prize that allowed him to spend two years studying under Martin Heidegger in Germany. Malik cut his stay short, however, once the Nazi Party rose to power and the political circumstances became untenable for him. He returned to Harvard and completed his Ph.D. in 1937 before returning to Lebanon and teaching at the American University of Beirut.

Malik recognized that a great deal was at stake in the final form of the UDHR. The deliberation over the content of this significant document was a proxy for debates that sprung from much more significant and nearly intractable divisions among the nations and cultures represented in the United Nations than those represented in any other constitutive document. “The first [issue of the Commission] is whether man is simply an animal, so that his rights are just those of an animal,” he wrote in 1948. He felt strongly that the UDHR could not merely address the material condition of men. “[U]nless man’s proper nature, unless his mind and spirit are brought out, set apart, protected, and promoted, the struggle for human rights is a sham and a mockery.” It is no surprise, then, that Dr. Malik was the primary author and advocate for Article 18, which addresses freedom of religion and freedom of conscience, these issues being most directly tied to man’s status as more than a merely material being.

His relatively brief time in Germany prior to World War II had given him first-hand exposure to the dehumanizing effects of a totalitarian regime. As a result, he took great care in advocating for careful and nuanced construction of the portions of the UDHR that did focus on the material, economic, and social conditions of man. A clumsy construction, he feared, could provide an entrée for an expanding government to reach into and regulate these areas of life. These areas must be protected, he argued, not for their own sake but as a “means to a higher end, namely, the freedom of spirit.”

He was concerned also by the rise of the materialist commitments of communism on the world stage as the primary threat to human rights and freedom of religion. Man must be, he argued, individually distinct from society. In an unpublished speech from 1944, just three years before the deliberations on the UDHR began, he expressed concerns for the future and asked whether, “any free separate personal life [will] be left to the ind[ividual] in the socialized world of tomorrow? Will the ind[ividual] be left alone, to seek, to see, to sin, to think, to pray?” The state’s abrogation of this “free separate personal life” would violate man’s very nature. To be fully human, man must be “free to think, free to choose, free to rebel against his own society, or indeed against the whole world, if it is in the wrong.” He understood the tenets of the Marxist philosophy that animates communism to be inimical to man’s true nature and as ably as he could attempted to deftly guard the language of the UDHR from its influence.

Conclusion

The appendix on the grounding of the UDHR observes, “An international declaration of human rights must be the expression of a faith to be maintained no less than a programme of actions to be carried out.” To some significant degree the faith that both helped create and maintain the UDHR and the dignified picture of the human person articulated therein is the Christian faith. In their own way Maritain and Malik, as well as numerous others, have attempted to promote a way in which practical agreement on fundamental features of the human person might be codified and respected in legal institutions.

If the contention that the UDHR is to some significant extent a product of a civilization and a historical, cultural context deeply informed by Christianity and even particular Christian thinkers is true, then it remains to be seen what salience might be retained as those influences fade. The Jewish philosopher Will Herberg wrote of a “cut flower culture” as a way to describe the inevitable fate of any society that removes its living, organic institutions from the environments in which they were originally formed and continued to flourish. In the same way we might rightly worry about the fate of “cut flower concepts,” which in one environment might blossom into a beautiful flower or bear a nourishing fruit, while in another context might well wither and die or, even worse, produce a poisonous toxin. Concepts like justice, dignity, liberty, and rights can have vastly different meanings and consequences for human life depending on what they are understood to entail and how they are used.

The UN Human Rights Council was founded in 2006 with a mandate “for strengthening the promotion and protection of human rights around the globe and for addressing situations of human rights violations and making recommendations on them.” One of the council’s subsidiarity bodies is the Social Forum, which is this year focused “on the contribution of science, technology and innovation to the promotion of human rights, including in the context of post-pandemic recovery.” The proceedings were held on November 2-3, 2023, as part of the UN Human Rights at 75 commemoration. Ali Bahreini, the UN Ambassador from the Islamic Republic of Iran, served as Chairperson-Rapporteur of the meetings.

The ambassador of a nation where it is illegal to convert from Islam to another religion, a right clearly affirmed in Article 18 the UDHR, had the honor of presiding over UN council proceedings on human rights. The dissonance was not lost on many advocates and observers. But the symbolic significance shows that the hope for practical agreement still has a long way to go 75 years after the ratification of the UN Declaration on Human Rights. Or perhaps it is simply a signal that the practical consensus that was still possible three-quarters of a century ago has diminished significantly in the intervening decades. Either way, the quest to acknowledge, affirm, and protect the merely human rights entailed by our common nature remains elusive and a basis for further work.