For better or for worse, the increasing political polarization and extremism we see today is no more than a reversion to the American norm.

Civic Friendship in America: A Madisonian Retrospective

Today at nearly the 2020 mark, many Americans harbor feelings of animosity towards their partisan rivals and consider them enemies of the common good. According to progressive commentator Sally Kohn, not only incivility but hate and cruelty are becoming all too common in our politics. The problem, Kohn believes, is not in our political disagreements and different identities—which should be celebrated—but in how we treat each other.

In this age of social media and anonymous blogging, there certainly is a problem with how Americans treat those with whom they disagree. But the actual substantive difference between deeply grafted political views cannot be so casually dismissed. Can a republic composed of citizens who disagree fundamentally about what is right and wrong endure? Or must the citizens share some fundamental principle(s) that make them one people? Is concord and civic friendship necessary or even possible in America today?

According to Aristotle, “the special business of the political art [is] to produce friendship.” Civic friendship entails like-mindedness in respect to the advantageous and just; it involves sharing a common or public opinion, which in turn informs public decisions and actions. As such, citizens will be concerned about the views and character of the fellow members of their polity. On many matters they will think differently, and even disagree passionately. Nonetheless, the bonds of their association are more than legal; they are also moral, involving public trust and goodwill. These bonds are a kind of pledge of protection and friendship which constitute the basis of a genuine republic.

This is all well and good for the small republic of classical times, but is there any sense in which Aristotle’s notion of civic friendship might be applicable to the modern American republic, with its extensive territory, diversity of interests and religions, commercial character, and differentiated labor?

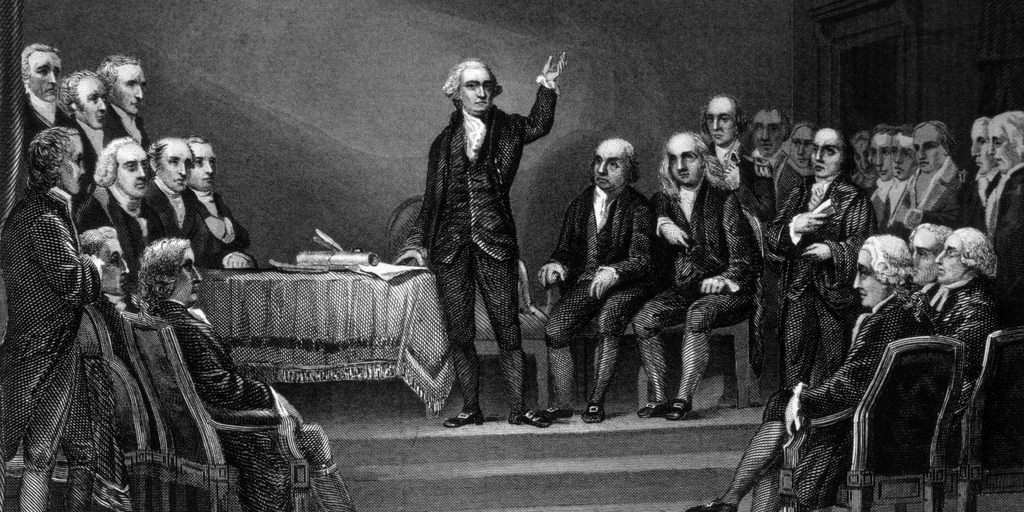

One of the chief architects of the U.S. Constitution, James Madison, recognized the benefits of a diverse society to control the effects of faction, though he also made clear that divisiveness was not the ultimate aim of his political theory. In the Party Press Essays, for example, he argued that Republicans are in favor of “banishing every other distinction than that between enemies and friends to republican government, and . . . promoting a general harmony among the latter, wherever residing, or however employed.” The goal of republicanism, he said, is to make “a common cause, where there is a common sentiment and common interest, in spight [sic] of circumstancial [sic] and artificial distinctions.” While Madison intended the large republic to make it difficult for a majority faction to form and communicate, the extent of territory was also meant to provide an environment conducive to the formation, refinement, and enlargement of public opinion. To accomplish this would require a complexly structured political system within this large republic, in conjunction with robust civic leadership by statesmen and private literati, capable of refining and enlarging the public views. When settled, public opinion was to serve as the stabilizing and unifying element of the political order. The purpose of the Madisonian politics of public opinion was to advance a “general harmony” in the “interests and affections” of “the great body of the people.”

In an article titled “Property,” Madison defined the reciprocity of rights as a “debt of protection” each citizen takes up and owes to every other citizen, according to the very nature of the social compact. As such, the American Constitution is both a legal and moral compact established by the people in 1789, and tacitly entered into by each succeeding generation. It is in this spirit that Americans pledge their ongoing public faith and renew the public trust.

In the politics of public opinion, Madison envisioned the people of America engaged in the ongoing task of making a “common cause,” whose joint civic labors would reinforce mutual civic trust and renew the bonds of civic affection, despite the differences that separate them geographically, economically, and religiously.

Fast forward two-plus centuries. Is Madison’s vision of forming a “common cause” via the deliberative politics of public opinion still possible today? Even if it is, it is not clear that twenty-first century Americans aspire to be one people with a shared ethos and common view of justice. Certainly, if the only thing that the two major political groups in America have in common is a dislike for one another, then there is no genuine civic union and the regime in any true sense cannot be long for this world.

In contemporary America, modes, speed, and ease of communication have burgeoned beyond the wildest imagination of Madison and the Founding generation. The Internet, and what it has spawned—Email, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter—have revolutionized communications across the face of the globe. With political communications as fast and facile as they are today, it is easy for people to unite on the basis of partial interests and prejudices. This results in a kind of contagion of passion and interest which is exacerbated by the echo chamber phenomenon, in which people tend to limit their sources of news and political ideas to those with whom they already agree. In a word, technology seems to have recreated the problem of the small republic, such that, given the ease and rapidity of communications over an extensive territory, the large republic is now susceptible to the disease of faction.

If technology has affected the process of forming public opinion, the changes in public opinion itself over time is as much or likely even more the cause of the present crisis. While some Americans continue to understand themselves and their way of life as grounded in the permanent human things, often expressed as natural law and natural rights, another group of Americans rejects the notion of nature, including the idea of human nature, natural law, and the permanent things in general. Instead, they view the challenge before the nation as one of either constructing a new and more inclusive egalitarian morality and/or deconstructing and destroying the old hierarchies of power. These two strikingly divergent perspectives characterize the political polarization in our society today, with conservatives (and some traditional liberals) on the one side of the ideological spectrum, and progressives (including democratic socialists and post-moderns) on the other. The distance between these two perspectives could not be wider or more pronounced: the disagreement is over the very meaning and purpose of human life.

We have certainly gone far down the road of political division, so much so that some are now asking whether there are two Americas. Nonetheless, to the extent that we still consider ourselves citizens of the same polity, we are obliged to engage with one another in public dialogue, despite our different views and perspectives. This is the first condition of free government and responsibility of a republican citizenry.

In accepting the mantle of American citizenship, each of us made a pledge, whether explicitly or tacitly, to every other American, based on the natural obligations we possess as human beings, one to another. This is the pledge of public trust that anchors the American republic and constitutes the bonds of our civic friendship. It is not merely a promise made by the Founders a long time ago. It is every bit as much our promise.

And it is the promise we today are asked whether or not we will keep.