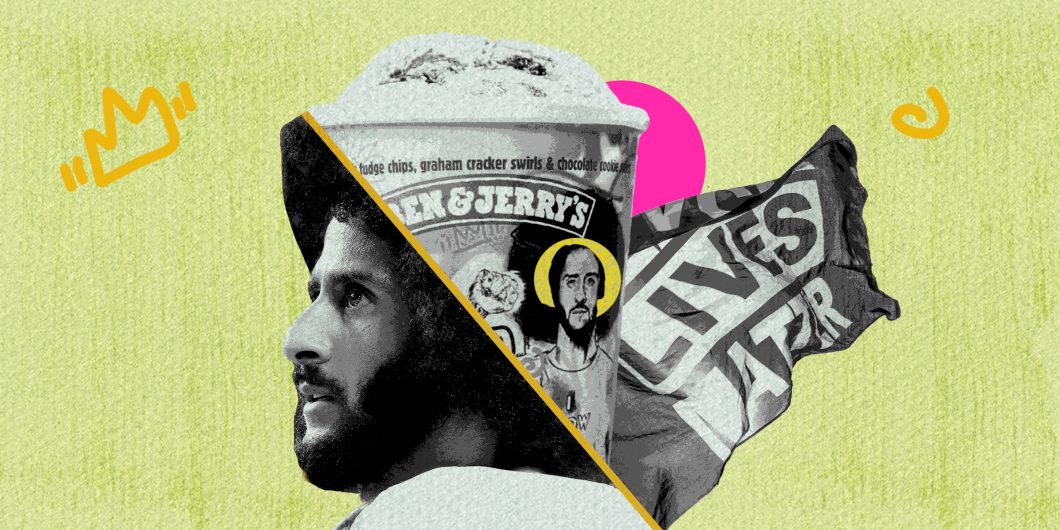

Colin Kaepernick: Sundae Justice Warrior

After losing his job on Sundays, serial activist/entrepreneur Colin Kaepernick is getting into the business of Sundaes. In addition to his lucrative contract with Nike, it was announced recently that the premium ice cream brand Ben and Jerry’s, well known for promoting left-wing causes, had agreed to produce a non-dairy “ice cream” named after the star social justice personality. Setting aside the fact that frozen vegetable products masquerading as ice cream is an abomination, this marketing arrangement raises a lot of interesting questions, particularly in light of the increasing frequency of businesses aligning themselves with prominent political and social causes.

This past summer you were probably one of the millions of Americans whose inbox was full of spam emails from various companies and businesses taking public stands on issues such as police brutality and social justice. I for one was amazed that businesses I patronized such as hotels, coffee manufacturers, online retailers, and others felt the need to tell me what their political views were on such matters. Shockingly, none of them came down in favor of police brutality or racism. Since I don’t choose service providers based on their political views and really don’t trust businesses making any public declarations of virtue, I was more than a little puzzled at this moral grandstanding.

Like many folks who support robust protections for property rights, markets, and liberty, I have long believed that the great Milton Friedman had the last word on whether or not businesses should engage in what he referred to as the “social responsibilities of business” in his famous 1970 New York Times article.

Friedman’s piece was a scathing rebuttal to the idea that companies should stray from their primary goal of maximizing profits. Friedman first noted that responsibility is normally attributed to individuals, not businesses. Therefore we have to turn our attention to the actions of individuals in their roles as executives or employees in the private sector. Friedman noted that individuals in their personal lives were free to believe whatever they wanted and support whatever causes they wished to. But the Nobel-winning economist argued that allowing those beliefs to dictate business practices violated the broader set of responsibilities people have when they are working in a marketplace. People often superficially describe Friedman’s argument as the view that businesses should simply maximize shareholder wealth, but he clearly states that when individuals in their jobs promote “social responsibility” the effects are far reaching:

Insofar as his actions in accord with his “social responsibility” reduce returns to stockholders, he is spending their money. Insofar as his actions raise the price to customers, he is spending the customers’ money. Insofar as his actions lower the wages of some employees, he is spending their money.

Wages are cut, consumers are forced to pay more, and shareholders receive less, including less to support philanthropic and social causes they support. And, of course, customers may not agree with the causes that businesses support.

Despite Friedman’s powerful argument 50 years ago, today this tendency to believe that companies should be supporting social and political causes has grown far beyond what Friedman was criticizing in the 1970s. Some of this can probably be labeled as “advertising” or “branding.” Take for example the outdoor clothing company North Face, which proudly tells consumers that it devotes a share of its profits to efforts to arrest climate change and protect the Arctic Refuge, works with down feather producers who obtain goose feathers in a “responsible” and sustainable way, and promises to collaborate with REI, Kelty, and Patagonia to fund a foundation called “The Conservation Alliance.” They take their activism even further with their recent “empowerment” efforts, such as supporting climbing wall access for disabled individuals, promoting youth engagement with the outdoors, and in 2020 encouraging more “inclusive” projects to give outdoor opportunities to minorities, no doubt in response to the protests and Black Lives Matters movement.

Outdoors companies are obviously playing this both ways. Their customers are much more likely to be wealthy white liberals living in blue states who support environmental causes and have the means to pay a premium for North Face’s upscale merchandise. However, the appearance of consumers wearing a brand with a reputation for social justice makes conspicuous consumption socially just consumption. If you drive a Subaru (which has long cultivated an image of high-minded social responsibility) to your hiking trip wearing North Face and eating Ben and Jerry’s ice cream, you’re probably a “First World” American. But by using products from companies with just political views you will be displaying the necessary sensitivity to Mother Earth, your fellow Americans of color, and even the poor geese who died so you could wear your coat. Assuaging guilt is part of this new style of branding and it sells. Conversely, conservative Christians are more likely to shop at Hobby Lobby and eat Chick-Fil-A—a restaurant that proudly closes on Sunday for religious reasons.

Which takes us back to Ben and Jerry’s, the ice cream that charges consumers a gigantic premium over regular ice cream for a higher quality product that is aligned with various causes of the left, including opposing jet travel for carbon emissions, supporting Occupy Wall Street, opposing drilling in the Arctic Wildlife Refuge, and a new podcast discussing the history of racism. Kaepernick, the personification of the Black Lives Matter protest movement, would seem to be a perfect fit for the little hippie ice cream company from liberal Vermont.

And yet pull back the curtain and the Wizard of Social Justice and Responsibility, Ben and Jerry’s, is actually part of the British multinational food company Unilever. Yes, Ben and Jerry’s founders who support Bernie Sanders and oppose gross forms of capitalism cashed out a number of years ago. And Unilever has its own lengthy list of causes it supports including sustainability, empowerment, health and nutrition, and various other high-minded vaguely titled initiatives it fosters in various countries throughout the world.

Unilever has taken all of this a step further because some of its causes and the means of achieving them are much more political in nature. Take for instance their relationship with Oxfam, which is an activist organization that addresses development issues from the left. On its blog, Oxfam has advocated that the winner of the 2020 election pursue the goal of an “intersectional feminist federal government” in its appointed government positions. They also support raising the minimum wage, raising taxes on the wealthy, and generally redistributing wealth through political means. And guess what? Oxfam also publicly ranks companies for being aligned with its positions on matters of policy. Unilever, which partners with and supports Oxfam, gets an extremely high score from the organization—shockingly. Don Draper would be proud.

So, you are probably saying to yourself—well Friedman would simply say that the market would discipline excessive spending on activities unrelated to business. Large shareholders would sell their Unilever stock and choose a company that is less inclined to spend its hard-earned profits on social justice causes. However, it appears as though the disciplining mechanism of the market has been disabled in today’s world of publicly held companies.

Since they are no longer responsible to actually put pressure on companies to pursue profits, the largest shareholders in major companies have turned their attention to supporting socially responsible business models.

At the exact moment we see widespread acceptance among corporate executives for businesses to engage in socially responsible activities, there have also been huge changes in the nature of public ownership of companies. Americans have adopted the practice of purchasing mutual funds, in particular index funds, rather than individual stocks in large numbers. Most, although obviously not all, individual investors don’t buy shares in Apple or Tesla or Alphabet—we buy an index fund that tracks one of the many market indices that are widely available to investors. The old model in which shareholders monitored and demanded a certain type of fiduciary relationship for individual companies is dying. Now huge institutional investors serve an unusual intermediary role between us and the companies we indirectly invest in, but this role is fundamentally different than the one Friedman envisioned.

The heads of these funds, who are far and away the largest shareholders of most major companies, don’t really care if companies have a single-minded focus on profit making. Why? Because these funds simply hold the companies in the index. If a large company decides it’s going to pursue intersectional feminist business practices or vegan dairy products to the detriment of their bottom line, there is no “interest” that motivates BlackRock, Vanguard, or Fidelity in trying to encourage that company from diverting resources from maximizing the bottom line. The fee structure that those institutional investors have doesn’t coincide with company profits. Large index funds charge very low fees to simply mirror a particular index, such as the S&P 500. The fund managers who hold the shares have no clear interest in maximizing profits at the companies as they are not paid more when companies make more money.

Since they are no longer responsible to actually put pressure on companies to pursue profits, the largest shareholders in major companies have turned their attention to supporting socially responsible business models. For example, recently the biggest manager of such assets, BlackRock, has become more visible in at least sounding as if they support socially responsible actions on the part of businesses and investors. The chairman and founder of BlackRock has started issuing public statements supporting socially conscious business goals that are targeted at the CEO’s of the companies his firm owns for their investors.

Whether these public pronouncements are merely PR or truly a shift in the preferences of large institutional investors is still unclear. BlackRock both responds to client preferences but also markets a lot of different investments, including socially conscious investment vehicles, and therefore helps shape those preferences as well. Either way, one thing is clear, there is a growing consensus that such actions are acceptable and required in today’s business environment. Do consumers reward such behavior? Some might very well value it, but clearly not all of them do. Shareholders should only support it with concrete evidence that embracing a socially conscious business model is actually profitable. For North Face and Nike, it may very well be a form of virtue advertising that management believes is necessary. For the vast majority of other businesses, it might not be and shouldn’t be encouraged if it costs investors money and employees raises and jobs. Ask an employee at a Unilever plant in the developing world if she wants to forgo a raise in her wages to support the cause of promoting feminist intersectional White House staffs and promoting Black Lives Matter.

Friedman was concerned that the specific political preferences of managers at publicly traded companies would supersede their fiduciary responsibility to maximize shareholder profits. But his bulwark against moralizing over profit maximization has been weakened, and ironically weakened by a phenomenon that has been widely lauded for increasing market participation and increasing returns to shareholders. His argument still stands—there is no economically justifiable reason for taking money from employees, consumers, and shareholders and giving it to individuals with political and policy agendas that are unrelated to the core business unless those businesses need such virtue signaling to succeed in their markets. But we have passed beyond that point. A particular political agenda is being pushed as just and fair and “correct” by businesses that have no need to play this game. If our elections are any indication, many market participants don’t support BLM or the rights of geese. Consumers don’t need to have their political views confirmed in a market. While consumers might have historically been free to shop around for less political businesses to patronize, the trend towards everyone jumping on the socially conscious bandwagon is real. And somewhere Colin Kaepernick, whether you love him or hate him, is laughing all the way to the bank.