Evaluating Religious Liberty in the States

Religious liberty was so important to America’s founders that they often referred to it as a “sacred right.” Virtually all state constitutions adopted after America’s break from Great Britain contained provisions protecting this freedom, but the federal constitution of 1787 did not. Federalists insisted that such limits were not necessary because the national government was one of enumerated powers, but the Anti-Federalists were not convinced and so insisted on the addition of a bill of rights, one that begins with these now famous words: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof . . ..”

Because the second of these two provisions, the Free Exercise Clause, did not apply to the states until 1940, the extent to which citizens and organizations were free to act upon their religious convictions was primarily protected (or not) by state and local governments. Since the mid-twentieth century, Americans have often looked to the United States Supreme Court to protect their rights, but the Court’s 1990 decision in Employment Division v. Smith severely limited the Free Exercise Clause’s reach. Simply put, the justices announced that so long as a law is neutral and of general applicability, it does not violate the First Amendment even if it keeps someone from acting upon a sincerely held religious conviction.

So, for instance, a law banning all adults from providing alcohol to minors is constitutional, even if it prevents a priest from celebrating the Eucharist with a sixteen-year-old. Similarly, a law prohibiting anyone from using peyote does not violate the First Amendment, even if it keeps some Native Americans from participating in traditional religious ceremonies.

In some important instances, the federal government has attempted to protect religious liberty against the states through statutory law, but by and large protections depend upon the states themselves. How well have they done?

To answer this question, the Center for Religion, Culture, and Democracy launched the Religious Liberty in the States project, with Sarah Estelle, an economist at Hope College, engaged to create an objective index that measures and compares how well states protect religious freedom. The first edition of the index and report was released last September, and the second edition of the index releases today, with a full academic report to come later this year. In its second year, the index considers 34 distinct items and 14 safeguards that are available in some but not all states. States are given a simple score of 1 for each item they protect, and a 0 if they fail to protect an item.

So, for instance, states that exempt clergy from prohibitions against serving alcohol to minors receive a single point on that item, whereas states that don’t receive a zero. Similarly, states that provide a religious exemption from vaccination requirements for school children receive a point, and states that do not receive no points. Aggregating fourteen safeguard scores produces one RLS index score per state. (An extensive discussion of the methodology is online at the RLS website and in the first year’s full report, available for download).

Significantly, the methodology of the RLS project is to allow states to identify for themselves when laws are religiously significant. Rather than starting with a checklist of what states ought to ideally do to protect religious liberty put together by a group of experts or advocates, RLS instead takes an inductive approach. When a state has taken action to protect the free exercise of religion and that action can be checked and verified against other states, that area becomes a candidate for inclusion in the RLS index. In this way, the frontier of safeguards measured by RLS is set by the states themselves. A score of 100% is thus eminently feasible, since any item included in the index is something that has been enacted by at least one, and most often many, other states.

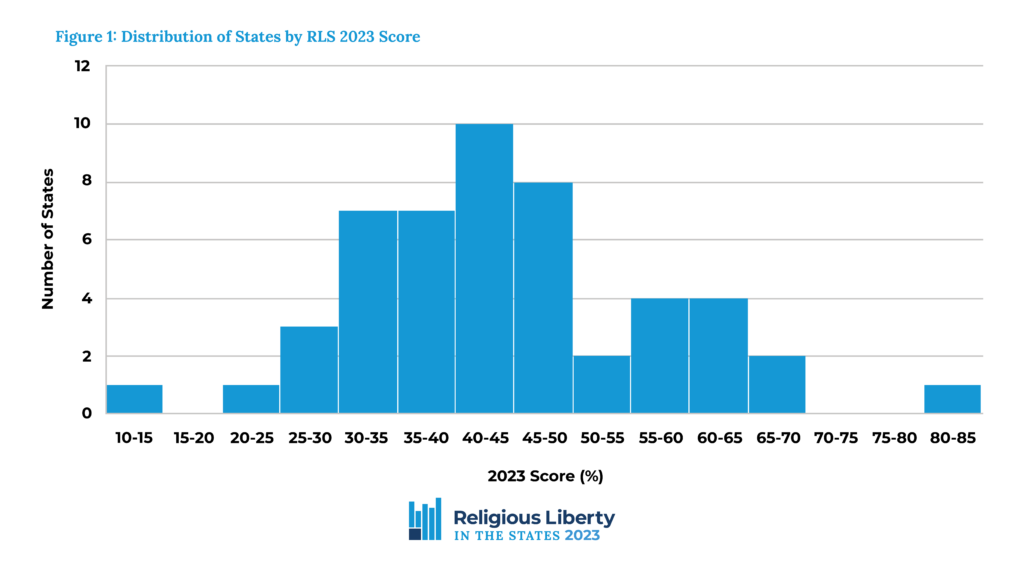

Perhaps the most striking finding of RLS 2023 is how greatly states differ. Illinois does the best job of protecting religious liberty, having adopted 85% of the possible protections identified in RLS 2023. West Virginia, on the other hand, does the worst job, having adopted just 14% of potential safeguards. Most states are somewhere in the middle, although a majority of them are doing less than half of what they could be doing.

The inductive methodology of the RLS project also means that there are existing resources for states to improve their protections of free exercise. The RLS dataset includes links to specific laws that have been identified and scored for each state. This permits legislators in a state that lacks a particular protection to easily consult laws in other states if they desire to adopt a similar protection for their state.

Religious liberty must protect more than the freedom to worship, but freedom to worship must be protected. Five of the thirty-four items considered in this year’s study involve clergy or religious ceremonies: (1) protecting the ability of clerics to decline to officiate at a marriage ceremony to which they have religious objections, (2) exempting clergy from mandatory reporting laws to protect clergy-penitent privilege, (3) permitting clerics to serve alcohol (wine) to minors in religious ceremonies, (4) protecting the ability of minors to consume alcohol in such ceremonies, and (5) permitting students to miss school for religious holidays.

Even though federal laws and judicial decisions tend to dominate the news cycle, there is a great deal of room for individual states to act to safeguard the free exercise of religion.

Most religious liberty cases do not involve worship, but instead concern neutral laws or policies that keep citizens from being able to act on their religious convictions or require citizens to violate those beliefs. One way states have attempted to protect these citizens is by passing Religious Freedom Restoration Acts. These statutes prohibit governments from restricting religious liberty unless they have a compelling reason and do so in the least restrictive means possible. Currently, 23 states have this important safeguard.

In an ideal world, protections against state action in addition to a RFRA would not be necessary, but in the actual world they are important as activist judges are far too prone to identify compelling interests where they do not exist. For instance, in no reasonable universe did Washington State have a compelling interest in requiring a florist, Barronelle Stutzman, to participate in a marriage ceremony to which she had sincere religious objections. Nevertheless, from the lower court judge to the state supreme court, jurists in the state identified such an interest. (Washington does not have a RFRA, but it ostensibly continues to interpret the religious liberty provision in its constitution to require strict scrutiny. The recent case 303 Creative interprets the Free Speech Clause to protect Stutzman and other creative professionals, but similar conflicts not obviously involving speech will still arise).

A virtue of specific protections is that they leave little room for judicial discretion. Must a cleric in Washington State participate in a same-sex wedding ceremony if he or she has religious objections to doing so? One can easily imagine an activist judge determining that the State has a compelling interest in forcing them to participate, but fortunately Washington specifically protects his or her ability to decline to do so: “No regularly licensed or ordained minister or any priest, imam, rabbi, or similar official of any religious organization is required to solemnize or recognize any marriage.”

It is possible, of course, to quibble with individual items or safeguards in Religious Liberty in the States. That is why the Center for Religion, Culture, and Democracy has made the full data set available and manipulable. We encourage others with an interest in comparing religious liberty to add to or subtract from the index, or perhaps to give different safeguards different weights. The project will continue to evolve, with the next report being released a year from now. We plan to continue to identify and add protections, and welcome suggestions about additional items that states may protect.

Even though federal laws and judicial decisions tend to dominate the news cycle, there is a great deal of room for individual states to act to safeguard the free exercise of religion. The RLS project focuses on identifying and tracking these safeguards through time, thereby creating opportunities for this critically important, and too often overlooked, space to be better understood. Religious Liberty in the States is an academic project, but it is not only an academic project. It is our hope it will encourage states to better protect what the founders called the sacred right of conscience for all Americans.