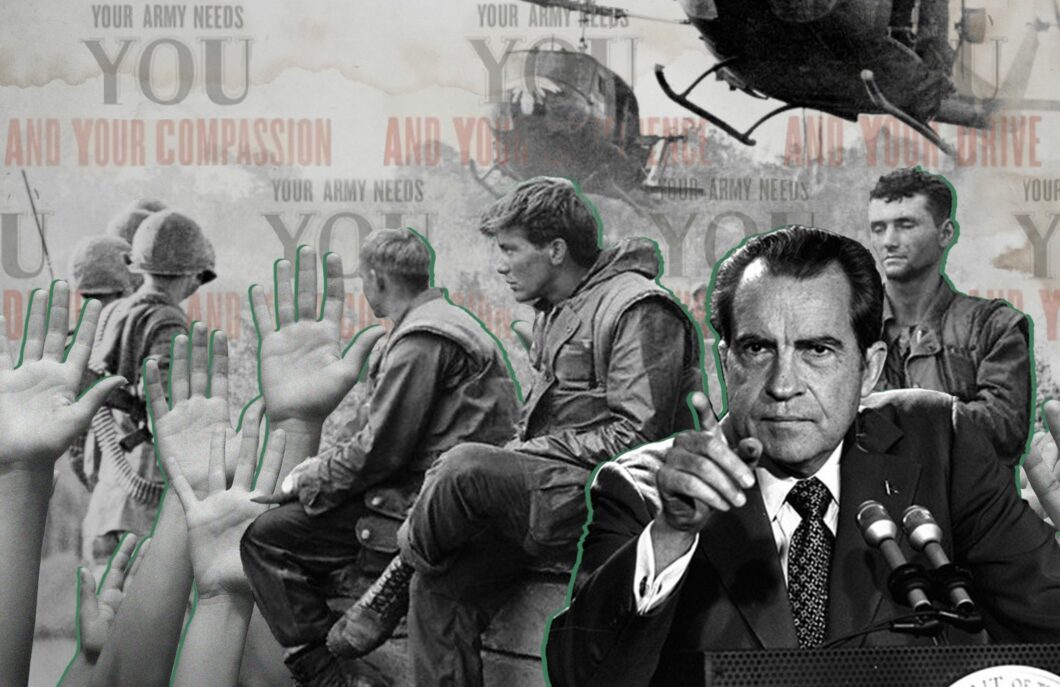

Fifty years ago, the All-Volunteer Force of the United States came into the world wrapped in the swaddling clothes of economic theories about rational actors and supply and demand. The free-market economists of the Gates Commission who stood godparents to the AVF (Milton Friedman and Alan Greenspan famously among them), had long been coaxing an already-sympathetic Richard Nixon into embracing a volunteer military. Only by unchaining the American military from draft dependency could the United States procure the better-quality soldiers needed for the complexities of modern warfare, they argued; fixing the military pay scale to better reflect civilian sector wages would be the key to attracting that requisite talent.

There would also, they avowed, be a secondary benefit to American democracy. Because conscription had proven to be inefficient, distasteful, and even dangerous for democracy, an entirely volunteer military would surely be more truly reflective of the central American value of liberty. This would strengthen civil society. Thus, an all-volunteer military would have the most widespread—and the most enduring—support from the American public.

Fifty years later, what’s more apparent is that there were some errors of calculation in the birthing of the AVF, however celebrated the AVF may be, and however valuable free-market principles may remain. Meeting the requisite accession numbers for a given year has repeatedly been a nail-biting scenario, especially for the US Army, even outside the twenty years of the Global War on Terror and despite needing nearly a million fewer pairs of boots due to repeated drawdowns in force size since the 1980s. That uncomfortable scenario has become a full-blown crisis of recruitment for two years running now, and with no relief in sight: few can answer Uncle Sam’s call, and fewer yet want to.

Likewise, a pay scale that has better matched the civilian labor market has never proved enough to attract and retain members of the military. Increasingly generous and expensive outlays in terms of benefits—ranging from education, health care, and housing to spousal and child support services—quickly were recognized to be essential to fielding the AVF. Benefits and better pay have subsequently changed the nature of the US military from a predominantly “singles” military (at least among the enlisted) to one of “Total Force Families,” directly contributing to the growth in size of the Department of Defense and thus “big government.” Those benefits, and their corresponding expansion outside of DoD, have similarly contributed to a heightened sense of entitlements and rights owed across all of society: Citizenship itself now is viewed mostly in transactional terms, rather than as a symbiotic relationship of rights and duties.

In hindsight, the miscalculation—or to put it more modestly, the problem—was threefold. It manifested over time and at three concentric levels: the military and the marketplace; the military and the government; and the military and civil society at large. What is most noteworthy today is how crucial yet invisible the last of these three elements has always been, because it is constantly taken for granted: On its fiftieth birthday, there’s a civic bill for the AVF that’s come due. But we seem unable any longer to pay it.

Rational Economic Incentives

The 1970s were not the first time that America employed a volunteer military, nor were the 1960s, the first in which arguments surfaced about the relative benefits and drawbacks of conscription. Up until the twentieth century, conscription had been in place less than eighteen total years out of the first 175 of America’s existence. But in the second half of the twentieth century, except for a brief year-pause between the end of World War II and the start of the Korean War, the possibility of conscription loomed large enough for the male half of society that it was a defining element of all of American society, from 1940–73. Anti-draft demonstrations in 1965 eventually led President Lyndon B. Johnson to appoint a special study commission on the Selective Service structure in 1966. Then, during the 1968 presidential campaign, Richard Nixon proposed ending the draft, as a narrow response to his political need to win the election and to the wider pragmatic need to quell what had become tumultuous—for all of society—anti-war protests.

Throughout the ’60s, building off of arguments raised by University of Chicago-trained Professor Gary Becker in the late 1950s, free-market economists both within (Martin Anderson) and outside of Nixon’s campaign (Friedman and Walter Oi) had been drumming the beat to Nixon’s eventual argument against conscription, which proceeded along three lines of reasoning. As Michael Gibbs and Timothy J. Perri expand on in their essay in the just-published The All-Volunteer Force: Fifty Years of Service, conscription was costly and inefficient—the constant turnover in conscripts meant that their training levels never met requisite levels of expertise for a technologically advancing military. The economic costs, furthermore, especially in terms of opportunity costs, fell unequally across society, especially affecting the poor and the middle class—conscription was thus a “hidden tax.” Finally, conscription in a free society was immoral: Conscription (as Barry Goldwater encapsulated it) “undermines respect for government by forcing an individual to serve when and in the manner the government decides, regardless of his own values and talents.”

Few thought that Nixon’s campaign promise about establishing a volunteer military would be among his top priorities once inaugurated. Within days of becoming president, however, Nixon tasked a less-than-enthusiastic Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird with forming a commission to develop “a detailed plan of action for ending the draft.” By March 1969, Nixon had announced the creation of what’s since become known as the Gates Commission, members of which notably included Milton Friedman, W. Allen Wallis, Alan Greenspan, William Meckling, Walter Oi, Harry Gilman, and Stuart Altman. Having further consulted numerous quantitative economic studies of “flexible elasticity” and the “hidden tax” that the draft imposed on conscripts, in 1970 the commission published its unanimous endorsement of a volunteer force.

Signaling how dramatic this was felt to be for all of society, the Gates Commission had the first chapter of its report publicized in the New York Times. Dispensed with—or at least devalued—in those first pages was the long-held traditional belief that each citizen has a moral responsibility to serve his country. Chief Justice Edward White had vigorously defended this view in the Court’s 1918 decision in the Arver (et al) v. the United States case of the Selective Draft Law Cases, with White even invoking Emmerich de Vattel’s 1758 classic Law of Nations along with defense provisions from several American colonial charters to bolster his reasoning. It’s worth noting that then, White’s opinion reflected a unanimous decision by the Supreme Court, despite the contentious novelty of sending conscripted US soldiers to Europe. It’s equally worth remembering General George Washington’s prior 1783 reflection to Alexander Hamilton, that “it may be laid down as a primary position, and the basis of our system, that every citizen who enjoys the free protection of a free government, owes not only a portion of his property, but even of his personal services to the defense of it.”

The army, at any rate, did not believe that young Americans ought to be viewed simply as rational economic actors. Nor the army as just any other employer.

These sentiments were out of fashion by the 1970s. Elevated in their place was a heavily economic argument about rational economic actors and competitive incentives. Of the three specific steps the Gates Commission authors stressed in order to achieve an all-volunteer force, they mostly emphasized the first: increasing first-term basic pay (the first two years of service) by about 75 percent, from $180 to $315 per month for enlisted personnel; second, making “comprehensive improvements in conditions of military service”; third, creating mechanisms for a “standby draft system” that could be activated “by a joint resolution of Congress upon request of the President.”

These arguments were made in a document that never even considered how the necessary marketing for recruitment could be done successfully in a public opinion space adversely impacted by the Vietnam War—while America was still fighting that war. (Nor the costs involved in mass marketing; nor the implications in terms of propaganda of the federal government paying for mass marketing about itself and some broadcasting companies profiting from that government advertising.) Nor did the report truly acknowledge changing cultural attitudes about youth and adulthood, personal responsibility and civic institutions, “revolt” from authority, and publicly acceptable behavior. But as journalist William S. White reportedly noted at the time in a Washington Post editorial: “The hang-up against the very term ‘military’ has reached a point little short of hysteria.” Marketing anything remotely related to the military, then, would not be on the order of promoting a Chevy over a Ford. It would be orders of a different magnitude. It would be expensive. And it would not achieve its goal on the strength of cash incentives alone.

The US Army, thankfully, was acutely aware of this—to defend that institution somewhat against the many extant criticisms about its reluctance to embrace the AVF model. Upon assuming his duties as army chief of staff on his return from Vietnam in 1968, General William Westmoreland had already seen the writing on the wall. He immediately ordered an in-house study of the feasibility of an all-volunteer army, followed closely by an even more substantial but “close hold” one, dubbed PROVIDE, for Project Volunteer in Defense of the Nation.

It’s not that the Westmoreland-led army rejected the marketplace model. They were just highly skeptical of the too-narrow one presented by the Gates Commission. They understood that the market in America was largely driven by consumer capitalism, a volatile thing involving emotions and subjective “favorability” factors. The crucial dynamic was creating and engaging consumer desire—selling images and dreams. But which eighteen-year-old’s dream is to die because of being employed in combat arms? More to the general point, as Westmoreland’s study advised: “The presence of income will not necessarily satisfy an individual’s motivational needs.”

The army, at any rate, did not believe that young Americans ought to be viewed simply as rational economic actors. Nor the army as just any other employer.

The Sales Pitch

However foreseen the eventuality of substituting an all-volunteer for a draft-dependent military may have been in certain political and military circles, when the mandate came, it came swiftly and with significant budget and congressional restraints to affecting that transformation—not to mention socio-political ones. There was no money budgeted for the transformation in the five-year plan for DoD’s budget, or even in the fiscal year 1971 budget for that matter. Even as President Nixon was publicly proclaiming the near end of conscription, he ordered US ground troops to invade Cambodia in April 1970. The public backlash was severe; subsequently, the army became even more dependent on the draft to fill its combat arms roles. The backlash within the army was likewise severe; desertion and absenteeism spiked, not to mention “other indices of indiscipline and bad morale.” The army can thus be forgiven for assuming that any transition away from a conscript-dependent military would happen gradually and during peacetime, or at least, once it was no longer in the thick of combat operations. But Nixon pressed on otherwise.

That the mandated 1973 transformation succeeded at all was thanks to significant but hurried legwork undertaken by the army, who early understood that an all-volunteer military meant in practice an all-recruited military. This is the story Robert K. Griffith, Jr. tells in his historical analysis for the US Army’s Center of Military History, The U.S. Army’s Transition to the All-Volunteer Force, 1968–1974. Caught uneasily in the logic of the era’s mass-market advertising, those having to manage the transition to the AVF found themselves being drawn into an unpalatable reframing of potential recruits as a “market”—then eventually, as “customers”—and the army itself, as a “product.”

The product they were selling would end up being the market research-based, advertising-driven image of the army, “whether as [a] site of individual opportunity or as consumer fantasy,” as historian Beth Bailey argues in her engaging study, “The Army in the Marketplace.” This was not necessarily military reality, which further complexified the public image of the military as an institution that could be trusted. And as over time the general population exploded while the number of those needing to serve contracted, the majority increasingly came to see the military through the lens of that marketed image, and what it conveyed about military service and its meaning. This then had to be reconciled against whatever negative account or scandal was reported on by the media.

Westmoreland’s PROVIDE study didn’t just illuminate the sudden need for sophisticated commercial advertising. It uncovered the need to completely rethink, reorganize, and expand the recruiting arms of the military. Under the direction of the Westmoreland-selected Lt. Gen. George Forsythe, (“Special Assistant, Modern Volunteer Army” or SAMVA), a staff of young officers set about gleaning whatever lessons they could from psychology (Maslow’s hierarchy of needs), from business (Ford, General Motors, and Volvo’s theories of what did and didn’t make work gratifying), from management theory (productivity), and from social science research (“needs” and motivations). But the study also reiterated what Westmoreland and the Pentagon could not unsee: that the army itself as an institution was in crisis, that its scandals were mounting while the integrity of the officer corps was declining, and that these truths could not be aesthetically erased through clever ads.

Westmoreland was ready to embrace an all-volunteer force as the mechanism through which to execute institutional reform and reestablish the army’s professionalism—which was the only thing that could truly improve the morale of those within the service branch, and thus the reality and “favorability” of the image of the army. Part of the work was more practical than philosophical: shifting non-essential military tasks like KP to civilian contractors; modernizing barracks with semi-private rooms; getting rid of “needless irritants” like morning reveille formations, to fit the “more informal and more oriented toward personal freedom” generation. SAMVA meanwhile launched a series of experiments, called VOLAR for “volunteer army,” for select commanders at three distinct army posts to try out different techniques along these lines with newly recruited soldiers. And because they believed that everything hinged on a rehabilitated image of the army among the youth especially, the army’s first marketing campaign tried to show how responsive it could be to their “needs” by proclaiming, “Today’s Army Wants to Join You.”

The first decade of the AVF was rough going, especially for the army. In 1977, the Carter administration was already engaged in contentious congressional hearings about the future of the volunteer military, as one of the foremost chroniclers of the AVF, Bernard Rostker, has noted. The costs kept on mounting, while the needed recruits kept on not materializing, even though their quality was slowly improving. The reality was that the pay increases were simply not sufficiently attractive to a wide-enough swath of society—additional benefits were needed.

There is a much deeper civic obligation to soldiers, that entails creating and maintaining a society that understands the ways in which it relies on its armed forces, existentially but also just to function day-to-day.

From the advent of the AVF, then-Assistant Secretary of the Army Carl Wallace had announced that 49 out of 51 recruiters had “stated that the GI Bill was one of the most essential sales factors in recruiting personnel.” It took a decade of recruiting struggles for army brass to be taken seriously when they insisted that the AVF could not exist without education benefits, as welfare historian Jennifer Mittelstadt has shown in The Rise of the Military Welfare State. Outside the Pentagon, the Reagan administration, individual congressmen, and other stakeholders began touting education benefits, whether funded or administered by DoD or the (then) Veterans Administration, as key to attracting and retaining a dramatically improved quality of recruit, one worthy of the proud legacy of being an American soldier. By 1984, when Mississippi Congressman Gillespie V. “Sonny” Montgomery successfully ensured a revamped GI Bill, (known since as the “Montgomery GI Bill”) that would apply to service members regardless of combat experience, the importance of educational benefits for military recruitment and retention purposes was widely accepted as an immutable fact within the Defense community and on Capitol Hill. Opinions differed on the proper composition of those education benefits.

Today, that understanding has been ratified numerous times over by detailed studies, surveys, interviews, and the popularity among the general public of big-ticket legislation on Capitol Hill centered on education benefits for veterans, such as the Forever GI Bill. We know without a doubt that those who join the US Armed Forces consistently cite education benefits as a top-three reason for joining in the first place. We also now know that historically, service-connected education benefits have been especially attractive on the front end to female and minority recruits, as well as to military spouses.

This is, of course, just one of the benefits that the federal government has had to offer to potential recruits. As federal financial assistance for higher education has increased throughout society, the value of military college benefits like the GI Bill has decreased. Healthcare benefits have arguably superseded education benefits here. From 2000–2019 alone, pay and benefits for the average servicemember rose 64 percent in constant dollars, driven most especially by large increases in health benefits. And while that combined compensation directly influenced growing numbers of servicemembers, especially enlisted, to renew their contracts up to the twenty-year career mark (adding the cost of more pensions to the mix), the escalating total costs have forced the military to reduce the number of its expensive core personnel and to turn to government civilians and contractors, who on average cost 25 to 40 percent less than their military peers, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

This, in turn, has fed the growth of the national security establishment. The large number of civilians employed in defense now allows it to be larger than it could possibly be if it were sustained by military personnel alone.

The Civic Cost

Over the past fifty years, “the military’s shift into the logic of the market has become naturalized and virtually invisible,” Beth Bailey writes. In a society of consumer-citizens, the framework of an “increasingly sophisticated effort to discover the desires and psychological needs of America’s youth and to offer the army as their fulfillment” helped to shift attitudes about “the obligations of citizenship to the opportunities of the marketplace.” While unintended, this has become one of the most consequential outcomes of the shift to the AVF, she contends.

This is the civic cost that the economists of the Gates Commission downplayed, if they noted it at all. That cost has several facets and affects both the military and society at large. Nor, importantly, is this the “fault” of the army or the military alone, for having ultimately embraced the all-volunteer model. There are difficult questions here, that are not easily resolved even by those willing to confront them. They reflect some of the core tensions of liberal democracies that celebrate liberty and individual rights, but that still have fiduciary duties of preserving their regimes, in part through fielding security and defensive forces.

Most American citizens are not preoccupied with these questions, having simply been born into this political community. They are not tracing out how that foundational social contract in fact entails multiple derivative, “mini” social contracts involving various aspects of American public, associational, and private life. Fielding a military is one of the most important of these. The largely unwritten, “second social contract” between society, government, and the armed forces considers not just how those armed forces will be regulated and made safe for a democratic government and society, but also the mutual obligations arising therefrom. As citizens in uniform, government and society owe soldiers the means by which to fill and replenish their ranks such that they are not laboring under impossible burdens.

We tend to think about society’s obligations to soldiers in terms of furnishing soldiers with the needed equipment and providing them with the necessary housing, food, health, and training provisions. But there is a much deeper civic obligation to soldiers, that entails creating and maintaining a society that understands the ways in which it relies on its armed forces, existentially but also just to function day-to-day. At that existential level, the obligations are more tangibly understood when presented in terms of civic education. We must foster and honor the civic knowledge, attitudes, and habits of individuals that are at the beating heart of a functioning democratic society, and through all means possible—whether formally through expanded and improved history and civics curricula; publicly through re-invigorated celebrations of the meaning of our civic holidays such as Flag Day, Independence Day, Memorial Day, and Veterans Day; or privately, through membership-based associations or daily family life.

Without a public civic education, both formal and informal, America cannot have a volunteer military. As the civic fumes of our grandfathers’ and great-grandfathers’ generation dissipate—who volunteered or were drafted for military service—the revealed truth is that we are now reaping the fruits of what we have not sown during the ensuing generations. For decades, America’s public schools have been diminishing to the point where civic education has almost disappeared, even while Americans have been withdrawing from the public and private associations in which they used to informally learn and practice civic habits. Obesity, mental illness, and drug issues afflict America’s youth, disqualifying the majority of them from military service, but these problems are all secondary to this more fundamental reality.

Unquestionably, the AVF has brought the country a more effective fighting force. But any public policy program of such a scale will have unintended consequences. Lost in the economic logic of the AVF is the fact that the American military is necessarily reflective of American society; it is downwind of society, as it were, and thus its various members often mirror the nuances of society in being expressions of its various parts. After all, the military is only able to recruit new members from that society. On its fiftieth birthday, this is the civic bill for the AVF that’s come due. To get to solvency then, and to unravel the true causes of today’s recruitment crisis, we must be willing to entertain the possibility that the Friedman coterie’s assumptions about an all-volunteer military were, if not outright wrong, at least problematic for what they ignored: the strategic civic reserves a democratic nation must have in the vaults of the hearts and minds of its people in order to sustain such an institution.