Putin thinks he is control. Another Russian, Leo Tolstoy, can remind us that so-called great men do not write the story of history.

Forgiveness as a Political Necessity

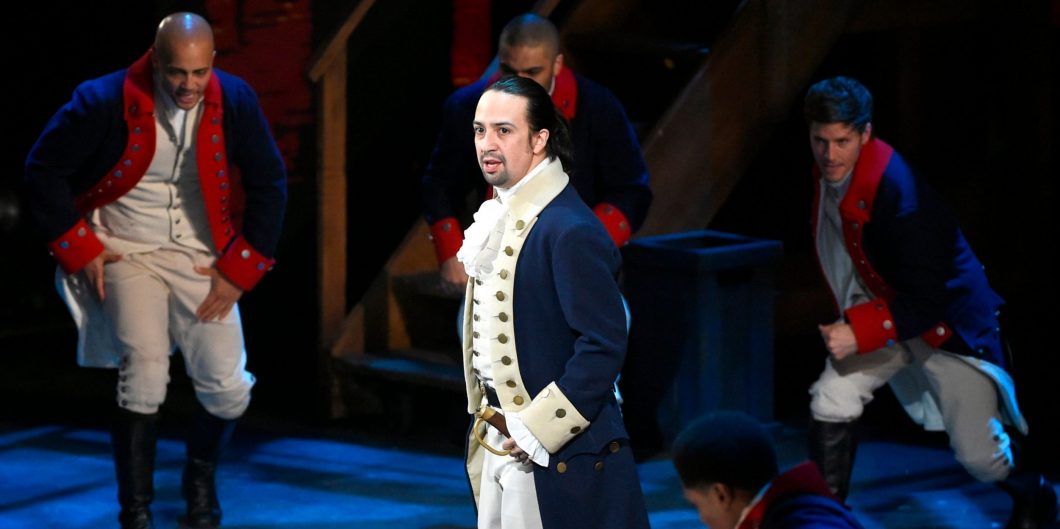

In an age of Twitter mobs and cancel culture, it’s becoming clearer every day that no cultural artifact or icon, no matter how old, banal, celebrated, or grandiose, is safe. One of the latest targets is the smash Broadway hit musical Hamilton. The tragicomedy of targeting a phenomenon like Hamilton is manifest in the reality that the musical actually has much to teach us about how to live, and perhaps even to flourish and prosper, together in the midst of injustice, turmoil, and suffering.

Near the opening of the show, a young Alexander Hamilton reflects on the prospects for the movement for independence. War, it seems, is a necessity; the revolution is coming and Hamilton is committed to fighting for it. But, he wonders, “If we win our independence, is that a guarantee of freedom for our descendants? Or will the blood we shed begin an endless cycle of vengeance and death with no defendants?”

In these brief lines Hamilton captures the two possible futures for America, one leading to life and the other leading to death. In recognizing these possibilities Hamilton shows himself to be a prescient student of history and the consequences of revolution. The dominant image called to mind by the word “revolution” is that of a wheel (from revolvere, “to revolve”) so that as the wheel turns, the cycle progresses. Those who were on the bottom end up on top and those who were on top are laid low—until the next turning of the wheel.

The problem with revolutions is that those who were on the bottom and are newly in charge very quickly use that power to tyrannize those who are now on the bottom. Using a complementary image, the Puritan Roger Williams was among those who observed that those who have been liberated from tyranny rapidly become tyrants themselves. Such hypocrites “persecute when they sit at the helm, and yet cry out against persecution when they are under the hatches” of the ship of state.

Thus, as Hamilton recognizes, those who have been wronged will eventually become powerful enough to avenge themselves on their oppressors; in so doing, they will create a new generation of the aggrieved, who will in turn repeat the pattern until it becomes “an endless cycle of vengeance and death.”

The only other option is one of new possibilities for life together, one in which the nation continually seeks to live up to the covenant made in the promissory note affirming the equality of all people before their Creator. Rather than retribution and revenge, this narrower path is opened up by a novel phenomenon: forgiveness. We see this new dynamic at work toward the conclusion of the musical, when Eliza Schuyler Hamilton somehow finds a way forward with her husband Alexander after betrayal and grief.

Eliza’s sister Angelica narrates their reconciliation, which is accomplished through Eliza’s forgiveness of Alexander. “There are moments that the words don’t reach,” sings Angelica, “There is a grace too powerful to name.” This is the unimaginable grace of forgiveness for those who do not deserve it. This is a grace that allows a relationship to exist in the face of unimaginable suffering and wrong.

Perhaps we can see easily enough how such forgiveness is a necessity at the level of personal friendships and even marriages. But does forgiveness have any role to play in secular, public, and cultural affairs? Can we think of forgiveness as a political reality?

If we make the effort, we immediately meet with an impediment. For if forgiveness has any corporate meaning for us at all, a society still sipping digestifs in the dusk of the long sunset of Christendom likely thinks of it—but only in a vague way—as little more than a relic of ecclesiastical procedure. This churchly association is no coincidence. Indeed, some political philosophers have looked to Jesus as the originator of our notions of forgiveness. In The Human Condition, Hannah Arendt remarks that “the discoverer of the role of forgiveness in the realm of human affairs was Jesus of Nazareth.”

But Jesus’s putative “discovery” of forgiveness does not, in Arendt’s view, make forgiveness purely “religious.” As she puts it:

The fact that he made this discovery in a religious context and articulated it in religious language is no reason to take it any less seriously in a strictly secular sense. It has been in the nature of our tradition of political thought… to be highly selective and to exclude from articulate conceptualization a great variety of authentic political experiences, among which we need not be surprised to find some of an even elementary nature.

Even if forgiveness had not been explicitly articulated as an ideal before the time of Christ, then, it might nevertheless be basic to the functioning of a healthy society: an “authentic political experience” of an “elementary nature.”

Christian theologians have themselves made the same basic point. The sixteenth century Danish Lutheran theologian Niels Hemmingsen, for example, does so in his Postil, or collection of sermons on the Gospel lessons for the liturgical year, while commenting on Luke 6:36-42, the text for the fourth Sunday after Trinity—a passage that begins, “Be merciful, even as your Father is merciful.”

Hemmingsen argued that mercy requires that we “forgive the one who has offended us for the injury he has done.” The claim is remarkable in this context because of the justification that he gives: “Since mutual offenses are many, if we did not forgive each other for them, no tranquility would be possible—in fact, the bond of human society would be rent asunder.” For without forgiveness the bond of society becomes the shackle by which we are imprisoned in an interminable series of retributions—what Arendt calls “the chain reaction contained in every action.”

With this comment, then, Hemmingsen makes an important broader point about man as a political animal: we must forgive not simply because there is a dominical command to do so, but because social life, for which man is made in his very nature, is impossible (at least in our fallen state) without such forgiveness. Or perhaps we might say that there is a dominical command to forgive at least in part because forgiveness is a general duty of nature in our present state, and not merely a luxury for the redeemed. We all offend in many ways, and if our only concern were with vengeance, our life together would be a Hobbesian nightmare, bellum omnium contra omnes. We need mercy more than Leviathan, even if we still do need legal justice. (And we most certainly do: “The gospel,” as Hemmingsen puts it, “does not abolish political order.”)

But the command to forgive in the gospel text actually upholds political order in a different way as well. We can return to Arendt once again to further expound why Hamilton’s opening dichotomy is so salient. Without forgiveness, we are left with an endless cycle of retribution that comes (and come it does) for everyone sooner or later.

By denying the past qua past, mere retribution destroys the present as well. Arendt puts it this way: “Without being forgiven, released from the consequences of what we have done, our capacity to act would, as it were, be confined to one single deed from which we could never recover; we would remain the victims of its consequences forever, not unlike the sorcerer’s apprentice who lacked the magic formula to break the spell.”

Arendt expands on this idea later. “Forgiveness,” she says, “is the exact opposite of vengeance.” Why? Because forgiving:

is the only reaction which does not merely re-act but acts anew and unexpectedly, unconditioned by the act which provoked it and therefore freeing from its consequences both the one who forgives and the one who is forgiven. The freedom contained in Jesus’ teachings of forgiveness is the freedom from vengeance, which incloses both doer and sufferer in the relentless automatism of the action process, which by itself need never come to an end.

Nothing is more purely reactionary than vengeance. Forgiveness, on the other hand, is the only reaction that is also a new action; it makes an end so that it can make a beginning. If vengeance lives only in the past, replaying the original offense on an endless and obsessive loop in the manner of Groundhog Day, forgiveness has the uncanny ability of effecting a genuine and surprising scene-change. The director’s “Cut!” is not a call for violence, but rather an opportunity for a second act. So, too, is forgiveness.

A society without forgiveness is like hell on earth. This is as true for societies on a smaller scale like marriage as it is for larger political communities. Marriages that last all have one thing in common: spouses that extend forgiveness to one another rather than withholding it. This kind of forgiveness is by no means the manifestation of a cheap grace. It is instead a grace, as Angelica Schuyler Hamilton describes it, “too powerful to name.” For Christians, forgiveness is only possible because of the costliest sacrifice imaginable.

As the political philosopher William B. Allen has noted, America itself is well understood as a “love story,” which includes “a moral commitment between the people and the government.” Forgiveness is the foundation of any true love story. Cancel culture necessarily ends either in self-immolation or in reeducation camps and gulags, creating its own kind of hellish existence—documented so powerfully by Solzhenitsyn. Forgiveness, by contrast, forges new beginnings and opens up new possibilities.

Or as that line from Hamilton wonders, “Forgiveness …. can you imagine?” Life together, as it turns out, is actually unimaginable without it.