Moralized Politics and the Challenge to Liberalism

Richard Garnett’s very helpful essay rightly frames consideration of the recent 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis decision in terms of the very broad question of the conflict between our commitment to fighting discrimination and the logic of the liberal constitutional tradition. He is one of a small number of legal scholars and political theorists who have for some time been calling attention to a large set of contradictions between these two contending democratic forces (see, for example, his 2012 essay “Religious Freedom and the Nondiscrimination Norm”).

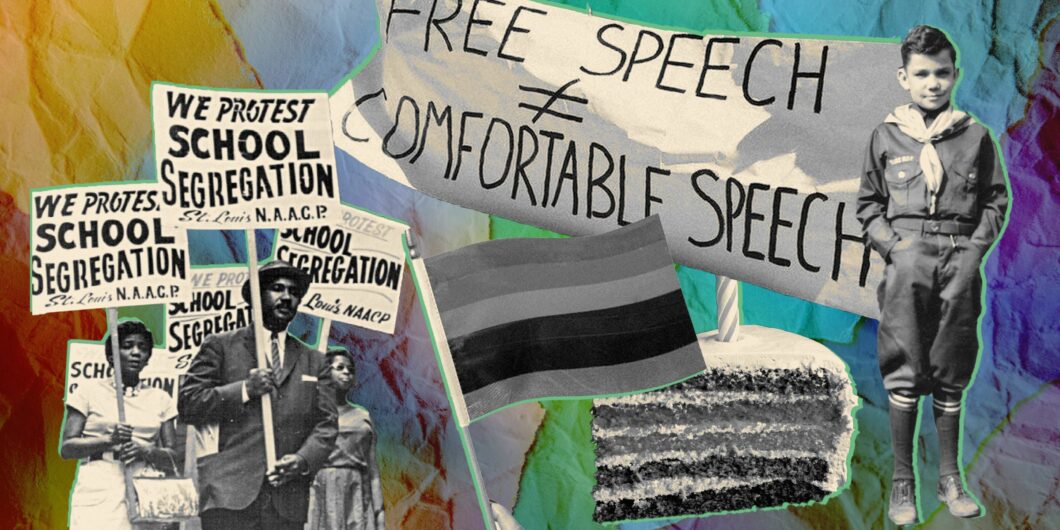

In an arresting way, constitutional law reveals clearly, and in vivid detail, the powerful challenges that the new order poses to the liberal tradition. Again and again we are confronted with the fact that the logic of the constitution has come under considerable pressure because of the war on discrimination. A massive challenge to freedom of speech is of course the best known of the tensions between old and new (there are at least a dozen important anti-discrimination policies that explicitly limit speech). But Garnett reminds us that religious freedom and the right of association are other key sites of struggle. We could add to the list the state action doctrine, claims about voting and representation, due process under Title IX, and several separation of powers debates as well (federalism, the power of the federal judiciary, the role of the administrative state).

Crucially, Garnett points us to what I believe is the most important point of difference or discord between liberalism and the anti-discrimination regime. This is when he has us consider both the fundamental moral claim that is made by anti-discrimination politics and our sense, powerfully rooted in the liberal tradition, of the dangers of moralized politics. As Garnett shows, the moral force of civil rights politics tempts some to think that the task of politics or government must be to “correct the errors of [our] thinking.” This—not the right of “association” as some would have it, or freedom of speech as many people assume—is the site of the deepest and most important divide between anti-discrimination and liberalism.

Garnett faces this most fundamental question of our domestic politics with admirable forthrightness. But he is also right to insist that this is not a contradiction that can be wished away. I agree with him when he indicates that there is no turning back from the civil rights revolution, no matter how much it is at odds with liberalism. As he says in his 2012 essay, “we believe that ‘discrimination’ is wrong. And because ‘discrimination’ is wrong, we believe that governments like ours—secular, liberal, constitutional governments—may, and should, take regulatory and other steps to prevent, discourage, and denounce it.”

But, as Garnett would be the first to say, that is not the end of the matter. Our question today must be how to learn to live with this new large and powerful political commitment and to find some way to reconcile it with our traditional understanding of things. It is of course quite possible that something good—a remedy for a sickness, for example (such as anti-discrimination manifestly was and is)—can have harmful effects or attributes. We need to learn how to face the task of improving the civil rights revolution—of reforming civil rights—where that is called for, and the first step in that direction will be to confront openly and honestly its limitations or defects. (The widespread sense today that there is something wrong with “wokeness” indicates that we have an opportunity to do so.)

I say this from the point of view of someone who is a conservative and I mean it as a strategy for conservatives. In my opinion conservatives are deer in the headlights on civil rights. They have to grant the major premise (discrimination is wrong) but then they don’t know what to do next because it seems to them that the Left owns the rest of the story. Partly because of this, some conservatives who rebel at the excesses of wokeness, etc., have begun even to be tempted to reject anti-discrimination as such, a stance that would have been unthinkable even 10 years ago. But that is a real mistake, both morally and politically.

Liberalism’s morality of freedom is sometimes said to stand exposed as somewhat lackluster by comparison, for anti-discrimination presses demands of justice upon us, relating to how we are to treat one another.

Conservatives need to figure out in a more deliberate way how to be at peace with civil rights without abandoning their eminently sensible criticisms of its excesses. Even though he might not put it this way, I do think Garnett’s essay makes some useful contributions in precisely this direction. Garnett’s main strategy here is to try to begin to find some way to distinguish among all of the many kinds of discrimination claims, and the many different contexts in which they are to be addressed by law. Not all forms of discrimination, of course, are wrong. “We discriminate,” as he says, “that is, we draw lines, identify limits, and make judgments—all the time.” Similarly, government cannot and does not prohibit all forms of discrimination. We imprison felons without apology, for example, and we institutionalize our “privileging” of farmers in the Department of Agriculture.

If a more complex and contextualized understanding of discrimination would make our thinking about it less strident and more rational, I would be all for it. And perhaps in the long run efforts along those lines may prove fruitful. But I have to confess that I consider this approach a bit too legalistic to be widely embraced.

I would like to consider two alternative strategies. Garnett himself suggests one of them, namely, to look to our liberal tradition for resources we might use to educate and tame some of the more spirited dimensions of our morally energized anti-discrimination politics. (I will return to this point briefly at the end of this essay). But, as a kind of preparation for that, I think we need to do more, first, to come to grips in a direct way with precisely the moral claims made by the anti-discrimination revolution. A task that especially conservatives and defenders of traditional liberalism need to undertake is to engage—respectfully but not simply deferentially—with the moral assumptions of civil rights politics.

Morality is the heart of the civil rights revolution. It is true that the anti-discrimination regime is at the same time an array of newly-important groups and a set of powerful new laws and legal institutions. These, in turn, have spread their influence in almost every area of life, in the workplace, in education, in the media, in all of the professions, etc.—in what conservatives now call wokeness’s “march through the institutions.” It is also true that civil rights politics often appears as a bewildering set of ideas (as an array of competing genealogies of intellectual history today are wont to emphasize).

But it is a moral claim above all that gives all of these developments their considerable power. And that moral claim is an amazingly simple one: racism, sexism, and other forms of discrimination are unjust and steps must be taken by the political order to confront them. It is this elementary moral insight that has made the civil rights revolution (apparently) unstoppable. Here liberalism’s morality of freedom is sometimes said to stand exposed as somewhat lackluster by comparison, for anti-discrimination presses demands of justice upon us, relating to how we are to treat one another. While the commitment to fighting discrimination may not be the command to love thy neighbor as thyself, it is surely something more than liberalism’s live and let live.

The new moral drama of civil rights politics is undoubtedly powerful but it does not settle all questions. For it is not simply our lingering liberal habits and sentiments that makes us wonder about legislating morality. As Garnett says, there is something about “campaigns against ‘discrimination’” that renders them “overenthusiastic or insufficiently deliberate.” How else to explain the efforts of the Colorado civil rights bureaucracy in the 303 Creative case inclining in the direction of, as Garnett says, “marginalizing, punishing, and re-educating those with at-present disfavored views on a few currently controversial questions”? The internalized demands of political morality shape life in a direct and obvious way. Much depends, then, on whether those demands are sound.

The high plane of our shared public morality is one important place where conservatives can begin to learn to be more at ease with the civil rights revolution. The moralism of civil rights politics makes conservatives uncomfortable because it appears to put them on the defensive. It is also a source of vexation for conservatives because at the farther reaches of the new secular moral claims being made there are concepts and commitments that seem dubious and unfamiliar—the moral terminology of identity, inclusion, recognition, respect, equity, and the like. This all seems foreign and unsettling to conservatives, and for good reason.

But it is precisely here that there is a very important opportunity to engage with the civil rights regime directly and in a beneficial way. If we are willing to think about the new morality it sets forth, to take it seriously and to reflect upon it, we may very well start to see places where its claims don’t add up. This will loosen its hold on us and authorize us to treat it in a more familiar way. The point of that exercise is not to turn away from anti-discrimination as such but, as I say, to learn to live under its reign—to make it better, more fair, more amenable to reason, and thus more humane.

To illustrate what I have in mind I want to examine critically the principle Garnett himself champions to express what is for him the basic moral claim or intuition of anti-discrimination policy, a specific form of equality. He cites Kenneth Karst’s “principle that people are of equal ultimate worth”—and, related to it, the “invocation of ‘personal dignity’” by the Supreme Court in their ruling upholding Title II of the 1964 Act, Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States. Assumptions of equal dignity or worth—and the language of respect and status associated with them—are common in civil rights discourse, and so one must say that they do capture something important in civil rights moral reasoning.

But there are serious problems with equal dignity claims—and with other arguments from equality—that provide some considerable portion of the ground of civil rights politics. This does not mean that anti-discrimination has no moral basis, but if we are to treat its claims with maximum seriousness we cannot but point out limitations where we see them.

What would such a respectfully dialectical engagement look like? To begin with, there is a political objection that may be made to arguments from equal dignity and equal worth claims, namely, that they represent a step in the direction of a more ambitious and manifestly untenable ideal associated with anti-discrimination politics—equal group outcomes. If one insists that all groups are equal in terms of their worth or dignity, how does one justify or ignore notable inequalities in income, health, criminal incarceration, education, and other conditions of life? Equal worth or dignity is not the same as equal outcome, but if we start from the former have we not admitted in advance a presumption of suspicion at least for any significant material inequality among groups?

A more fundamental problem with equal worth claims is that they can lead in a more or less direct line to the kind of projects of civic indoctrination that Garnett is rightly worried about. This is indicated by anti-discrimination theorist extraordinaire (and Northwestern law professor) Andrew Koppelman, who begins from roughly the same moral premise. In his illuminating book Antidiscrimination Law and Social Equality (another work highly attentive to the tensions between liberalism and anti-discrimination), Koppelman takes John Rawls to task for not seeing the full implications of his moral claims about equal worth or respect in the context of anti-discrimination politics. “Since [as Rawls says], ‘self-respect and a sure confidence in the sense of one’s worth is perhaps the most important primary good,’ the parties in the original position should not shrink from state programs of totalitarian reeducation where these would enhance the self-respect of the least advantaged. If the teachings of the church . . . damag[e] the self-respect of Jews or homosexuals, then the state [is] perhaps required to order the church to change its teachings.” I don’t think it would be easy for Garnett, starting from his particular understanding of equality, to resist the implications suggested by Koppelman. If one accepts the task of guaranteeing equal dignity or worth in the context of anti-discrimination politics, it is difficult to avoid the fact that such questions are bound up with individuals’ membership in groups, the identities of which are held to be partly constructed in terms of their status relative to other groups. It is not hard to see how such a stance renders projects of social engineering palatable.

One might say that there must be some equality claim at the bottom of our discrimination prohibitions, some standard that makes sense of what we mean when we say that Blacks are equal to Whites, or that women are equal to men. But it would seem there are more questions than answers here. To begin with, this cannot be a universal (Kantian, e.g.) claim about human rationality or the human person—because in civil rights politics all such claims are made on behalf of individuals always and only as members of specific groups. But it is certainly not obvious that all social groups are or ought to be equal in dignity or worth—and anti-discrimination does not even make such a general or universal claim, limiting its reach to a select few (those groups identified by the law). Surely anti-discrimination cannot hold, for example, that discriminatory individuals or groups are equal, morally, to anti-discriminatory individuals or groups. Another simpler, and more penetrating, problem with such claims concerns their ground, for claims of “worth” and “dignity” are positive claims, claims unavoidably associated with some standard of merit, and hence inequality, not equality. That is an unavoidable consequence of the words themselves; to deny that would be to insist that nobody can be “unworthy” or “undignified,” morally, a claim that anti-discrimination politics itself surely denies.

The point here is really from the other side of the coin: for let us not forget that liberalism was originally designed to confront and tame an order deemed harsh and punitive that was nonetheless justified by the highest of moral claims.

Moreover, when it comes to forms of equality associated with civil rights politics we see that there are actually many competing claimants for our attention, an embarrassment of riches. Older liberal notions of equal rights and equal protection of the law seem obviously important but do not extend their reach into the private sector, as anti-discrimination now does and seemingly must do. Equal opportunity does extend into the private as well as the public sphere but anti-discrimination today is clearly about more than mere “opportunity.” Arguments from equal worth or dignity (or, perhaps more commonly, “equal status”) do articulate a key intuition of civil rights politics, but as I’ve indicated, they lack a clear ground and thus appear as a kind of unjustified demand, not a solid moral principle. A demand for equal outcomes for groups (or some kind of group proportionality) is another important element at play in civil rights debate, but it is one that we can dismiss both because it is implausible on its face and because, politically, it is not embraced in an open and forthright way even by the Left (though it may well be promoted by surreptitious means or through terminological evasions like “equity”).

These reflections on our notions of equality are not intended to lead us to conclude, generally, that civil rights politics is lacking in moral power. To repeat, I agree with Garnett that the civil rights revolution was necessary above all because of the moral claims it makes upon us. But we need to do more to face squarely and to think about the moral reasoning of the civil rights revolution. An analysis of other moral ideals associated with anti-discrimination politics—concepts like identity, inclusion, recognition, respect, equity, social justice—is what we need if we are to make progress on this front. There is a sizeable literature here, the work of political theorists and legal scholars who have been wrestling with these concepts since the 1990s. Exploring their work will be helpful so long as we are attentive to the simple political meaning of these terms (and not primarily, I would add, their “intellectual” history) as expressions of the new order’s hopes and aspirations. (I have attempted a kind of preliminary reconnaissance of this territory.)

If we engage on this level, we will be taking anti-discrimination politics as seriously as we can. Where we uncover problems with its moral logic, we will also be to some extent liberated and empowered to think about it and to gain some critical distance from it. We are so much in the grips of the civil rights revolution that we—everyone, Left and Right—find it hard even to see it as a distinct phenomenon.

The goal of this project is to make civil rights politics more rational, more humane, and more liveable. We must recognize where the country is. The American motto ought to be: Civil rights, yes, but all the crazy stuff, no. Yes, of course we’re for civil rights. Nobody, Republican or Democrat, wants to go back to 1963. But neither do we like all the preachy and pedantic moralizing, the hypervigilant hypersensitivity, the censorship, the invasive pervasive regulation of our social intercourse by our co-workers and fellow citizens, and the harsh punitive measures (above all, the cancellation and firing, privatized and so without any due process) that seem somehow to enforce all of the above.

Starting from a more directly engaged understanding of civil rights politics, we might even learn to relax a bit about it. On something like that basis, it seems to me, we might also be able to begin to recall the full significance of our liberal tradition’s wariness of moralized politics. Here, too, Garnett’s essay helpfully points us in the right direction, in his insistence on the troubling dimension of not only compelled speech and what he names “compelled inclusion” but also, most worrisome, compelled thought or belief. Here especially First Amendment religion clause jurisprudence (and so not simply freedom of speech) offers some important resources we need, above all in the logic of the “coercion” test of the Establishment Clause and the act-belief doctrine of the Free Exercise Clause (and, behind them, the thought of figures like Locke). Those legal doctrines and their history teach in a powerful way that forbidding government intrusion into matters of thought and belief is a bedrock starting point for any consideration of the meaning of liberty.

It may seem odd to suggest that thinking about liberalism’s approach to religion will help us in the context of anti-discrimination politics, but I would not be the first to suggest that there is something quasi-religious about the American commitment to civil rights. The point here is really from the other side of the coin: for let us not forget that liberalism was originally designed to confront and tame an order deemed harsh and punitive that was nonetheless justified by the highest of moral claims. In that vast undertaking, liberalism was not entirely unsuccessful.