Book recommendations that will add some cheer to your holiday season.

How Civil Rights Law Changed America

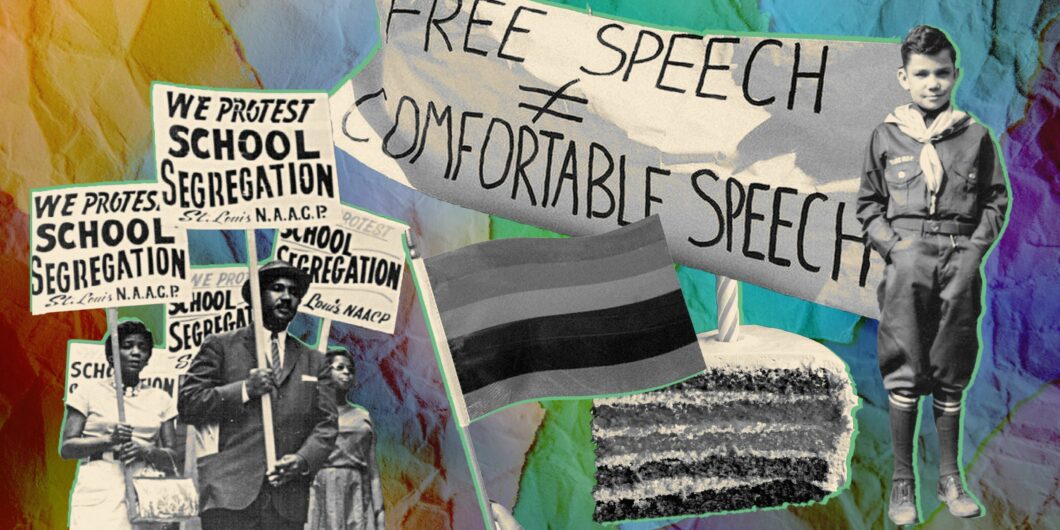

Over the last few years, antidiscrimination law has moved to the forefront of conservative commentary, as exhibited in recent books by Christopher Caldwell, Richard Hanania, and Thomas Powers. At the same time, antidiscrimination law has come to play a significant role in free speech and religious liberty law, evidenced in cases like Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission (2018), Fulton v. Philadelphia (2021), and 303 Creative v. Elenis (2023).

This Law & Liberty symposium is therefore coming at an ideal time to probe the relationship between antidiscrimination law and our constitutional order. Richard Garnett’s opening essay focuses on how public accommodations law has shifted over time, so that it is decreasingly about protecting personal dignity and market access, and increasingly about controlling what we think and how we communicate. I agree with much of Professor Garnett’s argument, but I will use my response to focus on three particular issues of potential disagreement between his view and my own writing on the subject.

The Constitutional Pedigree of Antidiscrimination Law

Garnett, after noting that “antidiscrimination rules are … pervasive in American law,” suggests that this area of law is rooted in the Constitution. His first example of the purported relationship between the Constitution and antidiscrimination law is that our Constitution “does not permit one state to discriminate against out-of-state commerce.” This is of course a reference to the so-called “Dormant Commerce Clause,” a doctrine that the Supreme Court had to make up because it is “dormant”—i.e., not in the Constitution itself.

That Garnett begins with such a dubious source is revealing of the limited constitutional pedigree for federal laws regulating discrimination. Indeed, Garnett proceeds to cite a motley collection of sources for the Constitution’s commitment to equality (the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, the text inscribed on the visage of the Supreme Court building, the Declaration of Independence, and the Gettysburg Address). While these various sources have something to say about the importance of legal equality in our system, they have nothing to say about the relationship between legal equality and private discrimination.

There is little reason to think, for example, that the Declaration of Independence, by proclaiming that we “are created equal,” means that we do not have the equal right to express our “Liberty” in associating with those of our choosing. If anything, the Founding Era’s conception of equality is opposed to antidiscrimination law, because the Founders’ understanding, as Thomas West has ably demonstrated, was that liberty, including the freedom of association, should be available to all citizens on an equal basis.

Whereas Garnett seems to believe that antidiscrimination law follows naturally from the Founding, and takes the fact that “antidiscrimination rules are … pervasive in American law” as evidence of this lineage, I would frame the relationship between antidiscrimination law and the Constitution in starkly different terms. Because the freedom of association lies at the core of the Founders’ understanding of equality and liberty, the pervasiveness of antidiscrimination law in contemporary America is evidence not of the legitimacy of antidiscrimination law but of how much of contemporary American law is inconsistent with the Founding.

The Historical Pedigree of Public Accommodations Laws

Just as Garnett misconstrues the constitutional pedigree of antidiscrimination law, he also overstates its historical lineage. While he rightly observes (in citing Adam MacLeod’s research on the topic) that public accommodations law existed before the civil rights revolution, Garnett errs in using that history to claim that “the Heart of Atlanta Court built on, and above, these earlier foundations.” To build on or above a foundation, it seems to me, is to follow the original design. But that is not what the civil rights revolution did. To the contrary, it built a new foundation according to an entirely new design.

Consider two related points on how this revolutionary feature is obscured in Garnett’s essay.

First, when he connects the Heart of Atlanta Court’s upholding Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to earlier public accommodations laws, Garnett ignores a critical disjunction between the two categories: Heart of Atlanta involved a federal law, whereas the earlier public accommodations laws (that Garnett references in citing the MacLeod essay) were state laws. Indeed, the only federal public accommodations law before the civil rights revolution was the Civil Rights Act of 1875, a law that the Supreme Court invalidated only eight years later, in the Civil Rights Cases (1883), on the ground that the federal government lacks the authority, under both the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments, to regulate private discrimination. And no one involved in the litigation—not even the lone dissenter (Justice Harlan) or the lawyers defending the law—seemed to think Article I could plausibly be interpreted to give the federal government this power over private discrimination.

Nevertheless, more than eight decades later, the Heart of Atlanta Court upheld Title II of the Civil Rights Act under Article I’s Commerce Clause, thereby initiating a dramatic departure in how we think of the federal government’s role in regulating intrastate, interpersonal affairs. Garnett’s analysis thus obscures an important feature of the civil rights revolution: how it made private, interpersonal conflicts a matter of national significance, subject to the shifting agendas of federal judges and bureaucrats.

Second, Garnett neglects how the civil rights revolution inverted the relationship between the freedom of association and antidiscrimination norms. Garnett rightly observes that, before the civil rights revolution, public accommodations law generally applied to three types of private businesses: (1) those exercising “monopoly power,” (2) those operating with a “publicly conferred license,” and (3) those exercising “a kind of chokepoint in the marketplace.” But he fails to explore why these three exceptions were so narrow in scope.

On this point, it is important to appreciate how, before the civil rights revolution, federal and state courts regularly upheld the freedom of association as a central feature of liberty. In a 1924 case, for example, the Supreme Court provided a long list of citations for how “it is the right, ‘long recognized,’ of a trader engaged in an entirely private business, ‘freely to exercise his own independent discretion as to the parties with whom he will deal.’” In fact, even on the precipice of the civil rights revolution, courts continued to hold that “absent conspiracy or monopolization, a seller engaged in a private business may normally refuse to deal with a buyer for any reason or with no reason whatever.”

It seems to me that Colorado’s punishing Jack Phillips for “wrong-think” is a logical outgrowth of, not a “dramatic overreach” of or “departure” from, the antidiscrimination norms developed during the civil rights revolution.

In other words, under the pre-civil rights paradigm, the freedom of association was so deeply rooted in our legal order that discrimination practiced by public accommodations could be regulated if and only if it truly were the difference, as Garnett writes, “between life and death, or cold and warmth.” But the civil rights revolution inverted this order, so that antidiscrimination norms became so important within our system that the freedom of association had to become the exception. This is why, under the civil rights regime, public accommodations cases that directly involve the freedom of association (such as Jack Phillips’s right not to bake a cake for a same-sex wedding and 303 Creative’s right not to make particular kinds of websites) must instead make strained arguments about religious liberty and free speech.

In sum, missing from Garnett’s analysis is that we call the civil rights revolution “a revolution” precisely because it overhauled our legal system, replacing central features of our constitutional order (such as federalism and the state action doctrine) with a new constitutional morality, centered around the good of diversity and the evil of discrimination.

The Epistemic Turn of Civil Rights Law

Finally, Garnett overstates the conceptual distance between how antidiscrimination law worked in the civil rights era, and how it works now. According to Garnett, “the Heart of Atlanta justices’ invocation of ‘personal dignity’ as well as market access was welcome and warranted.” But antidiscrimination law is now used, Garnett writes, to “correct the errors of [discriminatory] thinking” and “reeducate those with traditional, or now-disfavored, views about controversial questions.” Garnett finds this to be “a dramatic overreach, and an unwelcome departure” from the “welcome and warranted” protection of “personal dignity” and “market access” in the civil rights era.

Garnett is of course right that antidiscrimination law has expanded over the last generation, morphing into a right to demand services from anyone of one’s choosing, even if the reason for selecting that person is to penalize and thereby transform his or her way of thinking. As a result, it did not matter in the Masterpiece case that there were many similar bakeries in the Lakewood area; what mattered was that the gay couple wanted Jack Phillips to bake the cake.

Where Garnett and I may disagree, however, is that it seems to me that Colorado’s punishing Jack Phillips for “wrong-think” is a logical outgrowth of, not a “dramatic overreach” of or “departure” from, the antidiscrimination norms developed during the civil rights revolution. Garnett’s essay makes a big deal of the Heart of Atlanta case, but he ignores the companion public accommodations case, Katzenbach v. McClung (1964), which involved Ollie’s Barbecue, a small restaurant that, as the federal government conceded in the litigation, might not have had a single out-of-state patron in the year in question. Was it truly important for “personal dignity” and “market access” for the Supreme Court to manage this small restaurant’s seating policy? Or was the case more about “correct[ing] the errors of [Ollie McClung’s] thinking” about race relations?

We can see this feature of antidiscrimination law outside of public accommodations as well. For example, when the federal government penalized Bob Jones University, on the ground that its policy on interracial dating and marriage made the university ineligible for tax exemption as an educational institution under § 501(c)(3), the Supreme Court upheld this penalty because “the Government has a fundamental, overriding interest in eradicating racial discrimination in education.” The university eventually changed its religious views (in other words, “corrected its errors of thinking”) and thereby recovered its tax-exempt status. Again, was the federal government really protecting personal dignity and market access in penalizing this small conservative Christian university? Or was the government’s “compelling interest” in “eradicating racial discrimination in education” more about “correcting” an educational institution for teaching the “wrong” view on race relations?

In sum, the big difference between Garnett’s and my view of antidiscrimination law is that Garnett sees the Founding and civil rights revolution as fundamentally compatible in operating according to the same design (whereas I see more tension between the two, particularly in terms of how they conceive of national power and associational liberties), and Garnett views our current antidiscrimination law as a “departure” from the civil rights era (whereas I view them as fundamentally compatible in how they harness governmental power to eradicate discrimination and compel diversity).

Much of what underlies this disagreement is the pull of a type of “presentism” in conservative legal and political thought, drawing us to contend that antidiscrimination law was justified then (when it applied to “them”) but not now (when it applies to “us”). However appealing that pull may be to some, a more intellectually satisfying approach, it seems to me, is to consider all that we have learned about the antidiscrimination regime over the last 75 years—particularly in terms of how it applies asymmetrically, expands governmental power, and weakens community bonds—in thinking more critically about whether managing associational decisionmaking is the business of the federal courts in the first place.