While it would be good to address the government shutdown problem alone, it would be better to do so in a way that promotes less spending.

Moving on from Maslow and the Mystery Passage

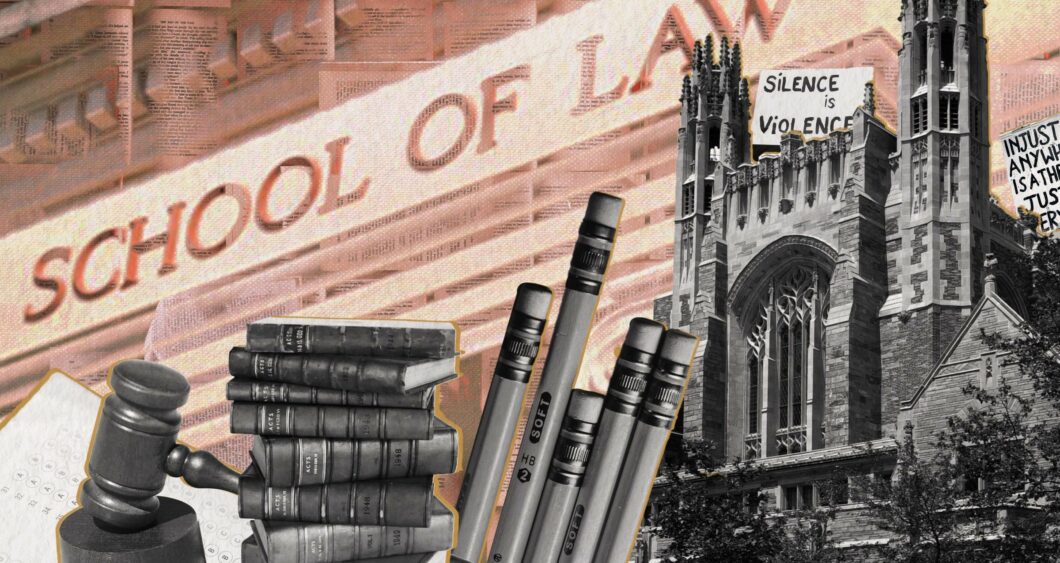

I thought everything in Professor Smith’s lead forum essay was inspired, so rather than disagree, I will just pile on. In the fall of 1968, when I began law school, the country was as riven as it is now. We were finishing an unpopular (and, many believed, unnecessary) war, we had three assassinations, burning cities, a tumultuous political convention in Chicago, a government that almost no one had faith in, and there was a pervasive feeling that the United States was coming apart at the seams.

No one in my family had ever been a lawyer, but I had always been told there was something special about the law, and that lawyers were cleverer, wiser, and more sensible than other humans. In those days, Latin maxims and law French terms had not gone completely out of use, and there was something romantic and exotic about even as arcane a topic as Civil Procedure—we were one of the last law school classes that learned common law pleading, and the dance of all the odd moves and stages of a trial was nothing less than wondrous.

Many of my fellow classmates were there to amass wealth and maybe power, but all of us were properly in awe of the titans who taught us, virtually all of whom used the Socratic method, and any one of which could reduce any of us to stammering stupidity. Still, especially for those of us who really had no idea why we were in law school other than it seemed like the thing to do at the time, we could sense that we had stumbled into something great—something that made us part of a three-thousand-year tradition stretching back to Greece, Rome, Sinai, and Jerusalem, something that linked us immediately to the grandeur of Europe—especially England, and something that was not just democratic, but also aristocratic and monarchical. We read Holmes’s words from the Path of the Law, and we, too, could not help but feel that we were hearing echoes of the infinite.

This was, of course, an atypical utterance from Holmes, whom we usually encountered as a pragmatist, if not a proto-legal realist. But if Holmes was an agnostic, this had not been the case with the great common lawyers (Blackstone thought Christianity was a part of the English Common Law, after all), and some of the framers of the Constitution itself, most notably Alexander Hamilton and John Adams, undoubtedly shared Blackstone’s belief. Adams once famously declared that our Constitution was made only for a religious people, and that it could work for no other. Indeed, in the first state Constitutions, even the most liberal, there were acknowledgments of the necessary nexus between law and religion—the Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776, widely regarded as the most radical and democratic, still required members of the legislature to swear they believed in the divine inspiration of the Bible and in a God who punished the wicked and rewarded the good. In a similar vein, in 1803, Justice Samuel Chase explained to a grand jury in Baltimore that there could be no order without law, no law without morality, and no morality without religion, and, as he was the son of an Anglican minister, by “religion,” Chase undoubtedly meant some strain of Christianity.

Though it was not uncommon to refer to the United States as a Christian country a few decades ago, the notion is practically anathema to many, if not most, political, cultural, and legal figures today. It is not surprising, given that believing Christians are a distinct minority among law school faculties, that emphasizing the close historical relationship between the English common law, the American Constitution, and Christianity is now a rarity in the academy. If I read Smith correctly, he does not regard this as a salutary development, and I share his concern. What, then, have we lost, and what might we regain if we seek to remember these religious origins of our country and our law?

A good summary of where we are now is the infamous “mystery passage,” attributed to Justice Anthony Kennedy, from the plurality opinion in Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), the dubious case that affirmed Roe v. Wade’s finding (now reversed) of a Constitutional right to terminate a pregnancy before fetal viability. Apparently believing that the abortion “right,” if one there was, had something to do with “liberty,” Kennedy bloviated, “At the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life.” Liberty most certainly has something to do with individual freedom, but no one alive was ever able, on their own, to define “existence, the meaning of the universe, or the mystery of human life.” These are things that can only be grasped through the efforts of one’s fellows, from literature, from culture, and, most of all, from religion.

In the legal academy today, it is nearly impossible to find anyone not tarnished by post modernism, and thus anyone who believes in timeless truths, and an objective single vision of the true, the good, and the beautiful.

And yet the unbridled, unrealistic, and impossible individualism that lies behind the mystery passage now appears to be the dominant ideology in the academy. It undoubtedly owes a lot to Freudian psychology, to Rousseau’s notion that civilization places us in chains, and, most of all, to the concept usually associated with Abraham Maslow, “self-actualization.” The core of this philosophy seems to be that each of us has an authentic “self,” and the goal of life ought to be to maximize individual opportunities to express and develop it. Surely this notion lies at the core of “trigger warnings,” of fear of patriarchy, of white privilege, and of “hate speech,” lest any of these evils interfere with true authenticity. What Professor Smith grasps is that the dominant progressive notions on our campuses, and, indeed, probably the push for “diversity, equity, and inclusion,” as well as the ideas that gender is socially constructed and fluid, are, at bottom, the inevitable consequence of the philosophy of self-actualization and the mystery passage.

This philosophy, we are coming to understand, rather than delivering more meaningful lives, isolates us from each other, and brings more loneliness and despair than richness and fulfillment. Surely this is understood by Professor Smith, and I read him as hinting that a return to the Christian worldview might offer something different. What might that be?

There are many mysteries involved in Christian theology, but for the purposes of enriching legal education, we needn’t immediately burrow into the Trinity, the virgin birth, the incarnation, the crucifixion, atonement, sanctification, or salvation. All we need, for starters, is to consider what Jesus said were the two basic elements of his Gospel message—first, love, honor, and worship God, and second, love your neighbor as much as you love yourself. It would be difficult to conceive of two notions further removed from the radical individualism of the mystery passage or the self-gratification of self-actualization. A return to a Christian understanding of our law would call for a recovery of altruism as the animating principle of the system. It might also lead to a reawakening of interest in promoting intermediate associations between citizens and their government, including religious and fraternal organizations, clubs, and local governmental, historical, and civic groups of all kinds—precisely the sort of thing that Tocqueville reported characterized our incredibly cohesive early nineteenth-century polity.

Might this be the sought-after means of reversing the lamentable centralization and polarization that have led us to an all-powerful federal government and bureaucracy and a poisoned politics where one party appears not to be willing to rest until it has incarcerated the leader of the other? It was Earl Warren’s famous pronouncement that one can’t turn back the clock, yet it was the renowned Christian apologist C. S. Lewis who not only claimed you certainly could turn back the clock, but when it fails to give you the correct time, you certainly should. In the legal academy today, it is nearly impossible to find anyone not tarnished by post-modernism, and thus anyone who believes in timeless truths, and an objective single vision of the true, the good, and the beautiful.

Steven Smith is a luminous exception to that rule, and he has it right. It is long past time to return to what we once believed: that true liberty cannot exist without the rule of law and a sense of a higher purpose to our striving. Before she was nominated to the United States Supreme Court, the then-Notre Dame Professor Amy Coney Barrett explained to a group of lawyers that they should conceive of their task as preparing for the eventual Kingdom of God. Professor Smith is pointing us in that direction, and it is the path we should now follow.