Anton inspires confidence both that the Founding was guided by the resulting theory of justice, and that that theory should still guide us.

Remembering the War

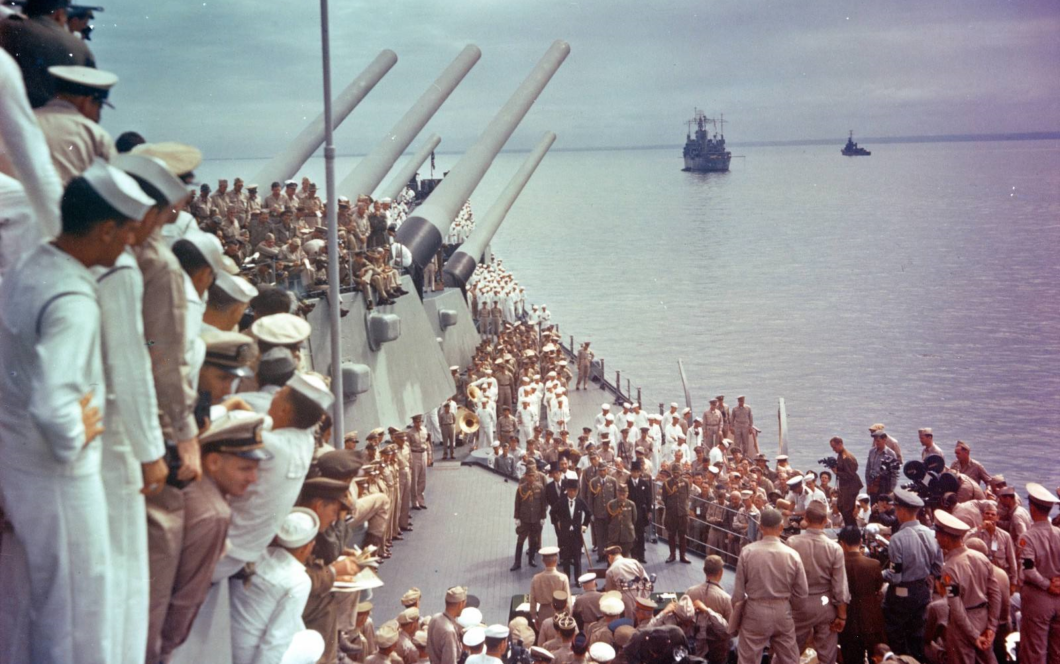

The Second World War came to an end 75 years ago. It was the largest, costliest, most lethal conflict in human history. It was fought by combatants from every inhabited continent on earth. Perhaps fifty million human beings died, mostly civilians—the last of whom died in the first and only use of nuclear weapons in warfare. The victors established a set of norms, institutions, and expectations that still—just—shape the world we live in. The war was an inflection point in history, a moment when things before and things after were palpably different from each other. Veterans sometimes gather to reminisce about their wars. But for humanity as a whole, there is still only one conflict that is “The War.”

What is the meaning of World War II today? What are its legacies, and what should we continue to learn from it?

Power and Grievance

Europe had never adjusted to Germany’s unification in 1871, and World War I did not resolve the issue. Though Germany had been defeated in the earlier war, many Germans insisted on the myth that their fighting men had been “stabbed in the back” by traitorous and cowardly civilians. Germany still deserved its rightful place in the sun, they believed, a place denied to them by the Treaty of Versailles and its provisions mandating territorial losses, disarmament, the notorious “war guilt” clause blaming the war solely on German aggression, and tens of billions of dollars in reparations payments.

Punishing Germany for the Great War may have satisfied the Allies’ moral demands but left the underlying strategic question unanswered: How to reconcile German power with European freedom? Rising power changes expectations, and global politics have to adapt or risk antagonism—but power that is either overweening or insecure threatens everyone. Like Chinese power and Russian resentment today, German power and German grievance were unresolved problems throughout the 1920s and 1930s, necessary but not sufficient causes of the Second World War.

Economic Collapse

It took global economic collapse to turn the German question into a catalyst for global war. The collapse started in 1929, when the American stock market collapsed—by itself, not dramatically different from the bursting of the dot com bubble in the early 2000s, the housing bubble in 2008, or the pandemic crash of 2020. The crash caused a precipitous decline in confidence and a dramatic decline of investment—a crucial engine of normal economic expansion. As businesses closed, one-quarter of Americans lost their jobs and consumers stopped spending, accelerating the downward spiral. From 1929 to 1932, global GDP, industrial production, employment, and international trade plummeted and did not recover for the rest of the decade.

The difference between today and the 1930s was that in the earlier crisis the loss of investment became a banking crisis as new loans dried up and defaults soared. The bank failures acted like dominos throughout the economy, taking down other business which depend on banks for financing. In contrast to the 2008 and (so far) 2020 crises, the U.S. Federal Reserve allowed banks to fail, did not cut interest rates, and allowed a contraction of the money supply, sparking deflation and further dampening consumer spending. The contrast might give us hope for today.

On the other hand, national policymakers then and today seemed intent on improvising their own solutions without coordination. International coordination is simply commonsense when faced with global problems like an international economic crisis, environmental decay, or pandemic disease. But the U.S. Congress passed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act in 1930 to try to protect American industry and Canada and European trading partners retaliated with their own restrictions, further choking international trade. In 2020, the European Union is fragmenting and the United States and China are in the midst of a trade war as the COVID-19 pandemic abruptly halts globalization: the world’s three biggest economies, accounting for some two-thirds of world GDP, are making trade and cooperation harder, not easier.

Ideological Extremism

Hard times make people fearful, anxious, and angry; they search for answers and for someone to blame; and they gravitate to ideas—and to men—that promise swift action, blunt solutions, and hard justice. In the 1930s, with economic collapse came ideological radicalism and political upheaval, most virulently in Germany but present virtually everywhere. Socialists, communists, nationalists, and a new movement that took inspiration from Italy’s fascista dramatically gained ground around the world in the 1930s.

The movements did not start in the ‘30s. Socialism and communism had been gaining ground for half a century. European Nationalism was as old as the French Revolution, and Japan’s Showa Statism had roots dating back to the Meiji Restoration. Italy’s Revolutionary Fascist Party was founded in 1915 and the National Socialist German Workers’ Party in 1920. It is important to note that, like German grievance, the existence of such movements predated the crisis of the 1930s and they were not a sufficient cause, by themselves, for global war.

Crisis is the opportunity demagogues need to turn themselves from charlatans into dictators. Nationalism and populism have swept the world in the wake of the 2008 recession, and are likely to gain new strength from the 2020 collapse. The fact that nationalist movements have been gaining ground for a decade means they are well positioned in 2020 to exploit the current situation—as they recently did in Hungary.

In doing so, they are following the example of their predecessors. The Great Depression was the crisis in the 1930s, and the decade saw a dramatic surge in these movements’ appeal, membership, and access to power. Fascist and fascist-like parties seized power in Portugal, Austria, Yugoslavia, Greece, Romania, Hungary, and Spain. The Nazi share of the vote in German parliamentary elections rose from 2.6 percent in 1928 to 33 percent five years later; the Communist Party rose from 10 percent to 17 percent in 1932. In January 1933 the German Chancellor invited the head of the Nazi Party, Adolf Hitler, to form a government, and Nazi Germany was born.

A Climate of Tyranny

As these movements took power, they first turned their attention to enemies at home—an oft-overlooked step on the path to global war. Dictators show their character in how they treat their own people: oppression at home is usually the precursor for aggression abroad. The denial of basic civil rights, like the freedom of speech, press, and worship and the freedom of political participation, are the canary in the coalmine, an indicator of worse to come. Unchecked government at home leads to unchecked ambitions abroad.

The Nazis are, of course, the most famous example. They used an arson attack on the Reichstag building (possibly set by the Nazis themselves) as an excuse to pass the Enabling Act in 1933, turning Germany into a dictatorship. Hitler oversaw a bloody internal purge of the party (1934), passed the Nuremberg Laws suspending the civil rights of Jews, Romani, and blacks (1935), banned free Christian churches and ended religious freedom in Germany (1937), and oversaw Kristallnacht, a national riot against German Jewry, in 1938. The Holocaust only differed in scale; anyone surprised that the Nazis turned out to be war criminals was not paying attention.

Italy had its own Racial Laws (1938) and Japan transformed into a nationalistic military dictatorship through the passage of a Peace Preservation Act (1925), the assassination of a prime minister by a military cabal in 1932, and the repression of another attempted coup in 1936. Even in western Europe and the United States, fascism and authoritarianism were in vogue among the intelligentsia, like H.G. Wells and Ezra Pound, and a much larger crowd was drawn to socialism and communism. Liberal democracy was seen as old-fashioned, unsuited to the demands of the 20th century and insufficient to meet the challenge of the Great Depression.

World order takes its character from the states which comprise it—especially from the strongest and most energetic states who act with deliberation and purpose to shape the world. After the war, world order took on the character of the liberal and (until the end of the Cold War) communist powers who won it. But before the war, the fascist powers of the 1930s were the chief powers who shaped the world—the “Axis” on which world events turned, as they accurately claimed. They acted with energy, vision, and speed to put their stamp on the world—illustrated first and most clearly by how they treated people at home.

International Aggression

The rise of authoritarianism at home was matched by aggression abroad. Ideological extremism and polarization made the peaceful adjudication of disputes essentially impossible. Italy invaded Ethiopia in 1935 and Albania in 1939. Germany embarked on remilitarization in 1935, seized the Rhineland in 1936, and annexed Austria and Czechoslovakia in 1938 and 1939. Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931, starting what would become the Asian theater of World War II. The Soviet Union made plans to annex Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia. And Spain descended into civil war in 1936, a conflict which became a proxy war between Europe’s communists and fascists.

The events that finally triggered war—the Nazi-Soviet Pact, Germany’s invasion of Poland, and Japan’s offensive across the Pacific—were not out of character; they were the latest in a long line of consistent behavior.

Up until Pearl Harbor, none of these conflicts in isolation was an existential threat to the United States. The democracies could—and did—plausibly tell themselves that they could afford to sit out the crises rather than risk escalation. Like Russia’s invasion of Georgia in 2008 and Ukraine in 2014, or China’s invasion of the South China Sea in 2013, North Korea’s acquisition of nuclear weapons in 2006, Iran’s attempt to do the same, or Syria’s descent into anarchy, no single crisis was, considered alone, worth the risk of global war.

Failure of Global Leadership

That is why, in the 1930s, the series of overlapping economic, diplomatic, and military crises needed one more ingredient to become a global war. The last crisis was the failure of the world’s other leading powers to mount a meaningful response to the Axis. In the face of international aggression and rising tensions, the League of Nations proved feckless, the United States proclaimed its neutrality, and the United Kingdom led efforts to appease Germany. The absence of global leadership by any single state, collection of states, or a world body meant the authoritarian powers faced no real obstacle to their aggression. Each act of aggression was rewarded with victory, inviting the next act, and then the next.

By inexorable logic, Germany, Italy, and Japan came to convince themselves that they had a right to rule the world. The rest of the world had to choose between letting them or fighting for their continued existence.

The world did not lack for alternate ideas. Liberalism and democracy may have been unfashionable, but they were widespread and widely understood in Europe and the United States. The problem was not that fascists won the debate, or that communists persuaded the world. The problem was that liberals were cowards, their governments were miserly, their armies were underfunded, and their leaders were passive. They did not want to lead, and fascists had bigger guns. In the face of global crisis, citizens of free nations were intent not merely on putting their interests first, but defining their interests as narrowly as possible, without regard for any notion of a shared or common good that the last global war should have taught them. And the war came.

Legacies to Cultivate

Many of the lessons of World War II have been ingrained so deeply that they have become trite to us: appeasement of dictators is a bad idea; liberty and human rights are superior to fascism, oppression, and tyranny; and leaders should be accountable to their people and—perhaps most importantly—they should be held accountable for crimes. We should be grateful that these ideas have become clichés: better to live in a world in which such truths are taken for granted than a world, like the 1930s, in which people and nations disagreed with them or, in some cases, would have found them simply unthinkable.

Some other lessons of the war were uncontested until quite recently, yet they are worth salvaging despite having fallen out of favor. Most importantly: cooperative security is a key anchor of world order. That can be a difficult notion to sell to the public in 2020 because it requires each nation say that it is not fully secure unless and until its neighbors are, that an attack upon one is an attack upon all. It requires nations to defend the principle of non-aggression, even if they are not the victims of the aggression in question.

American voters have cooled on this idea, opting instead for Donald Trump’s “America First” foreign policy, and polls in some European states show fewer than half of respondents support defending NATO allies. But FDR’s analogy of lending your hose to a neighbor whose house is aflame still rings true: fires in the neighborhood of nations tend to spread. Regional cooperative security remains vital in light of Russia’s recent record of invading its neighbors, North Korea’s proliferation of nuclear weapons, Iran’s support for terrorism, and China’s aggressive disregard for international law in the South China Sea.

A related legacy of World War II worth salvaging is a healthy skepticism towards nationalism, not allowing nationalist sentiment to obstruct international cooperation. This is a complicated issue because, of course, it all depends on what nationalism means. Some Europeans, in reacting to the excesses of fascism, have sought to transcend nationality altogether by trying to turn the European Union from a trading block into a new kind of identity, which seems a classic case of overreaction. State sovereignty, cultural particularism, and patriotic affection are positive goods in human life which do not deserve the opprobrium in which the anti-nationalist sometimes holds them.

But it is also true that nativism, xenophobia, racism, chauvinism, and militarism have historically accompanied nationalist sentiment with alarming frequency, a timely reminder when nationalism is finally resurgent again after more than seven decades. Victor Orbán has explicitly championed “illiberal” nationalism in Hungary; nativism and xenophobia are on the rise across most of the developed world in reaction to the immigration and refugee crisis; and white nationalism has again reared its ugly head.

Even mainstream nationalists are guilty of their own over-reaction and threaten to throw out all the positive benefits of international cooperation. When they deride international cooperation and cooperative security as “globalist” threats to sovereignty, rather than acknowledge them as essential anchors of world order, it does not reassure anyone that they are talking about the good kind of nationalism. Finding the right balance between national attachments and international responsibility is as urgent today as it was 75 years ago.

Lessons to Unlearn

Some of the legacies of the war merit reconsideration. The war was fought under the banner of the Atlantic Charter, one of whose principles was self-determination. That idea was, and continues to be, muddled in theory and fraught in practice. It is so unclear what it means—who is the “self” who deserves independence?—that it has provoked wars over who gets to define it. States use it to defend themselves and non-state actors also use it to demand secession and partition—and there is no lower boundary on how narrowly and specifically such identities can be defined, leading to a never-ending revolution of new identity groups against any older ones. Any norm of international law that cannot be defined with any precision and leaves scores of wars and failed states in its wake is best discarded. Sovereignty is good and essential, but that does not mean we need to buy into a Romantic-era notion about peoplehood to decide who gets to be sovereign.

Similarly, the war gave birth to the United Nations and, eventually, the school of liberal internationalism in international relations scholarship. Liberal internationalism involves a host of ideas about the importance of international institutions, diplomacy, soft power, the legal equality of all states, bargaining, compromise, and persuasion. Essentially, liberal internationalism in international relations scholarship is a kind of ex post facto justification for the UN system and is affiliated institutions. It makes claims about the vital importance of such institutions, the dangers of hard power, and the mutability of the world’s evils with enough effort, resources, and good will. It is un-reformed Wilsonianism, pure Enlightenment optimism about humanity’s ability to improve its condition.

Liberal internationalism as a unified theory is nonsense (even as both liberalism and internationalism are separately important ideals that should continue to guide U.S. foreign policy). Its optimism is naïve and utopian. Contrary to liberal internationalism, power is the esse of politics, and power often does flow from the barrel of a gun, to mix aphorisms from Paul Ramsey and Mao Tse-Tung. States that ignore the realities of power are derelict in their duty: the pursuit and use of power is not simply an obvious truth of international politics; it is what states have a duty to do because power is a prerequisite for any kind of peace or justice in the world.

That is why, during and after the war, the American theologian Reinhold Niebuhr rightly criticized liberal internationalism for its “fatuous and superficial view of man,” excoriated “statesmen and guides [who] conjured up all sorts of abstract and abortive plans for the creation of perfect national and international communities,” and damned “the sentimental softness in a liberal culture [that] reveals its inability to comprehend the depth of evil to which individuals and communities may sink.”

Nonetheless, liberal internationalism somehow became the default ideology of the American and European foreign policy establishments after World War II. The war should have taught otherwise, but somehow scholars and policymakers paradoxically used the war to justify a theory of how the world works at odds with what the history of the war actually teaches—a theory that, in practice, is more apt to cause the next war than prevent it. As I have written elsewhere, democracy is a better idea than fascism, but the liberal international order does not exist because it is a better idea. It exists because the democratic powers built bigger and better guns, killed millions of fascists, overthrew fascist governments, tried and hanged fascist leaders, and liberated or coercively democratized former fascist countries.

Today there are scores of universities churning out thousands of civilian policymakers with degrees in public policy, diplomacy, international affairs, and “global policy” (whatever that is), blinded by the naivete and functional pacifism of their liberal internationalist education, marching straight towards the cliff of disarmament and irrelevance.

Ideas Matter

That is not to say that contemporary, academic realism is any better. Some kind of classical liberalism—that is, a politics centered on human liberty and human dignity—is essential to making political life bearable and internationalism is simply necessary to confront global challenges. Most forms of contemporary realism deny these simple truths, focused as they are on bean-counting the indices of material power; defining the national interest as narrowly, literally, and myopically as possible; and denying the importance of values, culture, norms, history, and identity for the shape of the world and thus the context in which national security takes its meaning.

Policymakers and scholars like Hans Morgenthau, Henry Kissinger, and Kenneth Waltz emerged from World War II believing that any morality in politics was a straight road to utopianism or even fascism. They founded the modern schools of realism with the express intent of denying a role to values, culture, and ideology in foreign policy. Realism is best understood as principled opposition to moral aspiration in politics and a belief in the self-justifying nature of state power and state sovereignty—an ideology that was intended to undercut the claims of liberalism abroad but ends up doing so at home as well.

More to the point, realism describes a world that does not exist, a world detached from the moral aspirations of real humans. This “realism” is the least realistic theory of international affairs. Its proponents today—like Christopher Layne, John Mearsheimer, and Steve Walt, the foreign policy experts at the Cato Institute, the newly formed Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, and the scholars and policymakers associated with the “national conservatism” movement—argue that American security is independent of the fate of global democracy, the United States can withdraw from most of its commitments abroad, and that the United States faces few meaningful threats to its security. And that is why, in response to today’s challenges, they have nothing to offer: no meaningful guidance, no valuable lessons, and no relevant policy prescriptions. They learned all the wrong lessons from the last global war.

Ideas matter. We are not secure in a world in which our most fundamental beliefs are ignored, disputed, trampled on, thwarted, or violated by strong, well-armed tyrants across the world. Ideas matter because the culture of world order matters. After World War II—and again after the Cold War—the United States led the free world in putting its collective stamp on world order. For the better part of a century world order bore the stamp of liberal ideas, liberal culture, and a free way of life. And for that time, the world was safer, more stable, more prosperous, and more free than during any comparable stretch of history.

Recognizing that does not require us to endorse all the naivete and utopianism of the liberal internationalists. It only requires us to marry a commitment to liberal ideals as our polestar to a prudent and pragmatic appreciation for the inescapable role hard power must always play in human politics.

Conclusion

After decades of retreat, autocracy is once again on the rise. Vladimir Putin has been strikingly successful in his re-imposition of autocracy in Russia, playing a weak hand expertly. Chinese President Xi Jinping halted and reversed liberalizing reforms and concentrated power even more firmly in his hands since assuming power in 2013. Venezuelan democracy died in 1999. Turkish democracy had died a slow strangulating death since Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s assumption to power in 2003. Egyptian democracy was stillborn in 2011. Nationalist and populist movements have eroded democratic norms in Brazil, India, the Philippines, and Poland. That is why Freedom House wrote that “democracy and pluralism are under assault” in its annual report on Freedom in the World. The assault is not new. It has been gathering strength since 2005: “2019 was the 14th consecutive year of decline in global freedom.”

None of these developments individually constitute a deathblow to the liberal international order, just as none of the autocracies’ acts of aggression are existential threats to the United States. Another Russian landgrab in Eastern Europe, a North Korean provocation south of the 38th parallel, another Iranian attack on Saudi Arabia or one on Israel, the dissolution of the European Union, or the acceleration of nationalist and authoritarian gains across the world in the crucible of a Second Great Depression—could each be shrugged off as regrettable but survivable developments, quarrels in faraway lands between people of which we know nothing.

But the global drift away from democracy and towards authoritarianism collectively alters the character of world order, which is today markedly less free and less open than before. Some World Health Organization officials reportedly played down the threat of the coronavirus and praised China’s response to it because they did not want to risk offending the Chinese government. We already live in world in which protecting Chinese prestige outweighs transparency, accountability, and public safety.

More worryingly, the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing global economic collapse have now provided the crisis which demagogues at home and tyrants abroad will exploit to their benefit. Hungarian democracy voted itself out of existence in March when Prime Minister Victor Orbán, long at the forefront of the nationalist trend, won unchecked power from the parliament to fight the pandemic, a playbook that others are sure to follow. And China is advancing an aggressive propaganda campaign advertising its leadership while peddling an outrageous conspiracy blaming the U.S. for a public health crisis largely of its own making.

Even without an old-fashioned campaign of territorial conquest, aggressive Chinese and Russian leadership of an illiberal world order is not hard to imagine, much as the German-Japanese Axis altered the character of world order in the 1930s. In fact, Chinese predominance and the triumph of illiberalism is now the most likely scenario for world order in the 21st century given the unchecked trends of the past few decades. The liberal powers have done little to halt or reverse their own decline, the rise of authoritarianism, or the authoritarians’ international aggression.

Does that mean another global war is imminent? It is possible that the liberal powers might willingly, peacefully cooperate in the transfer of power to the authoritarian great powers rather than risk conflict. There is good reason to doubt that will happen. The only precedent for a peaceful power transition among great powers is when the United Kingdom aided and abetted the United States’ rise because their interests, values, and beliefs were so closely aligned. No such relationship exists between the United States and China. Already there is a growing backlash against China’s handling of the coronavirus and calls for a wholesale reevaluation of the relationship.

More to the point, there is no compelling reason to accept Chinese or Russian leadership, the death of the liberal international order, and the compromise of American values such that we enjoy them only at the sufferance of the Chinese Communist Party. The choice is not between Chinese leadership and World War III—at least, not yet. If the allies had confronted Germany when it seized the Ruhr in 1925 or the Rhineland in 1936, it is unlikely Germany would have risked war then and they might have even prevented Germany’s further aggression. War might have come eventually, but if the Allies had confronted Germany and Japan earlier they would have been better prepared, the war might have come at a time of their choosing, and the war might have been shorter and less costly.

The worst course of action would be for the liberal powers to delay, avoid a decision, and passively accept events shaped by the authoritarian powers until they really are forced to choose between destitution and conflict, between slavery and war—the same choice the democracies faced in 1939. None of the crises instigated by authoritarian aggression individually are existential threats to the liberal order or to U.S. security—but collectively they signal the death knell of the free world and the American way of life. Because of that reality, we will almost certainly wish, on hindsight, that we had acted sooner, that we had not waited until the crisis is unavoidable, until we heard the snapping of the first vertebrae on the dromedary’s spine.

World War II started when preexisting national grievances met economic catastrophe, which in turn led to ideological radicalization, the rise of nationalism and authoritarianism, and eventually international aggression—all enabled by the vacuum of global leadership by liberal powers. Read that sentence again and note how eerily it describes the world in 2020. We are at risk of remembering World War II by fighting its sequel, teaching the war’s lessons by reliving them, and remembering its mistakes by recommitting them. Unless we take drastic action, we will commemorate the end of the Second World War by replicating the path to it.