Joseph F. Johnston's book asks why nations fail, and how we should understand America's national despondency.

Freedom, Faith, and Community

I thank both David P. Goldman and Bradford Littlejohn for their comprehensive and thoughtful reviews of The Decline of Nations.

Goldman makes a number of valid points, including very insightful comments on religion. America, as Goldman says, cannot help being religious. “It isn’t that Americans have ceased to be religious, but rather that the Christian categories of sin and redemption have morphed into racial or class guilt and Woke atonement for the sins of racism, misogyny, homo- and transphobia, and so forth.” This is correct, as demonstrated by the behavior of America’s radical left in the last year or so. I agree that “neither the root of our problem nor its possible solution is to be found in philosophy. . . . Nothing but a new Great Awakening can save America.” I should have made this point more clearly in the book, and I am grateful to Mr. Goldman for making it so well in his review.

In the book, I have tried to describe the strengths of the United States, including its heritage of individual liberty, economic prosperity, federalism, and the rule of law, while addressing certain adverse trends such as a decline in the industrial base, unnecessary foreign interventions, an inadequate system of public education, damaging social trends (such as the decline of marriage, the family, morals and religious practice), excessive government centralization, and irresponsible government spending. In a complex society, such counteracting trends exist together. To describe these conflicting strengths and weaknesses is not an inconsistency but a necessary feature of historical analysis.

Littlejohn implies that I am a doctrinaire believer in laissez-faire but he also observes, correctly, that I repeatedly emphasize the central importance of community, identity, tradition, and the rule of law. Surely it is possible, in a free society, to have the proven advantages of free markets, private property, and limited government (the principal components of “laissez-faire”) while at the same time pursuing policies that favor family, faith, tradition, and community. That is what the book advocates.

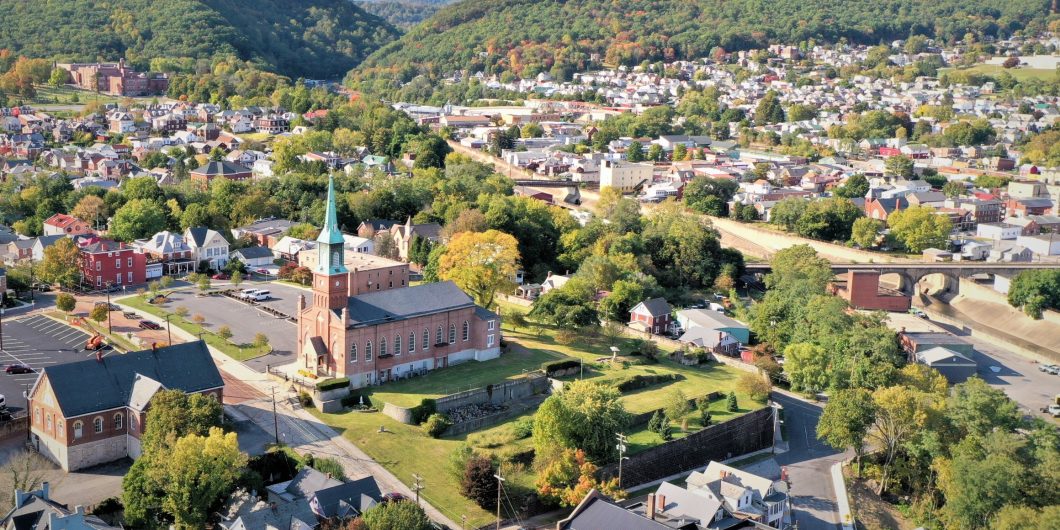

In discussing the book’s alleged omissions, Littlejohn asserts that “the devastating decline of American manufacturing does not even register on Johnston’s radar.” Apparently, he did not focus on Chapter 3, “The Economic Base,” in which this point is specifically addressed (“The loss of jobs and business investment due to globalization and unfair competition resulted in the near-destruction of some older industries and the decline of a number of cities, especially in the Midwestern ‘rust belt'” and more). The issue of trade is also addressed in this chapter.

Littlejohn asks, “Who is this book for?”—a fair question. He suggests that conservative readers are already aware of the book’s examples of decline, which he dismissively describes as a “laundry list.” But the book was not written just for conservatives—it is also for all those who might be interested in history, in learning more about some of the trends that have damaged American society, or in what might be done to restore and maintain our freedom and prosperity.

I hope that both the book and our exchange here may spur such reflection.