The Founders displayed the power of man's rational nature, instead of merely asserting it.

Human Rights are Natural Rights and Natural Rights are Human Rights

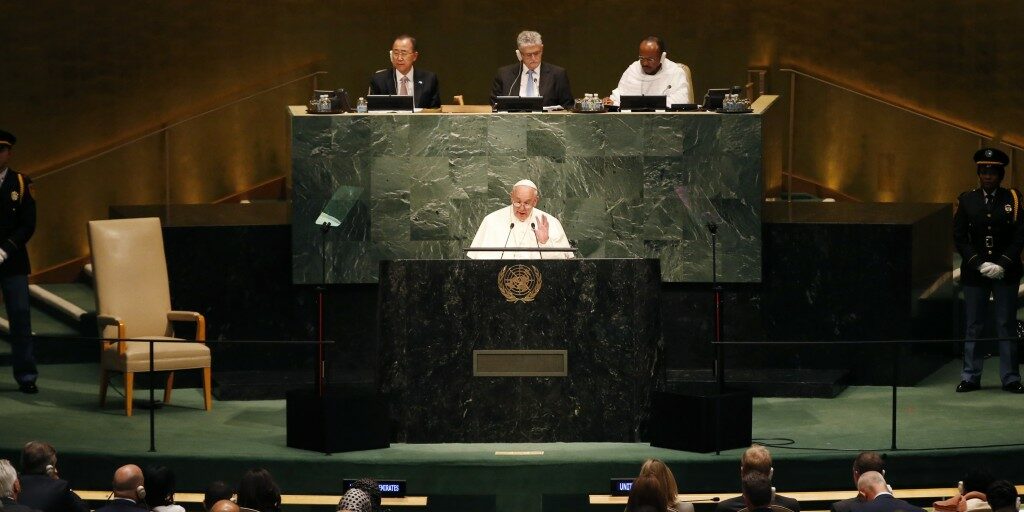

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights ranks with the Magna Carta and the United States Constitution as a font of global political norms. 48 states voted to adopt the Declaration at the United Nations General Assembly in 1948, none opposed it, and eight abstained. Two international covenants emerged in 1966 that rendered human rights legally binding on their signer states. Human rights courts and institutions emerged in Europe and Latin America. After World War II, rights proliferated in the world’s state constitutions, the average of which now contains 48 rights according to the website, Constitute. Human rights are foundational in international humanitarian law, which governs armed combat, and a central standard in the International Criminal Court. NGOs are dedicated to promoting human rights in general and to certain human rights in particular, such as that against torture. Human rights pervade political speeches and debates, the foreign policies of states, scholarly writing, university classrooms, and newspapers around the world.

Will human rights be as prominent 75 years from now as they are today at the UDHR’s 75th anniversary? Their fate depends, I contend, on whether people recognize human rights as expressions of natural law, the set of moral norms that humans apprehend through reason. If so, human rights will be robust around the globe; if not, they will be chaotic, impotent and vanishing.

It may seem imprudent to insist that human rights be recognized as natural law. “[W]e agree on these rights, providing we are not asked why,” French philosopher Jacques Maritain quoted one of the framers of the Declaration in his Walgreen Lectures in December 1949, published shortly thereafter as Man and the State. He was remarking upon the formidable task of eliciting agreement among a philosophically, ideologically, and religiously diverse set of framers, a story that legal scholar Mary Ann Glendon has told masterfully in her book of 2002, A World Made New: Eleanor Roosevelt and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Was not such agreement possible because framers did not insist that the Declaration pronounce the words natural law, or, for that matter, God?

In the years since the Declaration, political philosophers in the West have given more and more attention to what they regard as the problem of pluralism. How is it possible to have a just and stable society—and still more, robust international agreements—among people divided by a plurality of doctrines? This is the question that John Rawls, the past generation’s most influential political philosopher, took to be the central one of the latter portion of his career. Given pluralism, is it not foolish to enshrine one philosophical view in a declaration for which one hopes for global receptivity?

Although, admittedly, the enunciation of any one doctrine may prove a practical obstacle to international agreement, let us not be too hasty to set aside natural law’s indispensability for human rights. Shortly following Maritain’s well-known quotation, he said, “from the point of view of intelligence, what is essential is to have a true justification of moral value and moral norms . . .. The philosophical foundation of the Rights of man is Natural Law. Sorry that we cannot find another word!” Nor should we be too hasty to conclude that natural law is absent from the Declaration. The very concept of a human right embodies natural law. A right is an entitlement that a person invokes and that other persons have a corresponding moral obligation to respect. Human means that every person claims this entitlement and every other person is obligated to respect it. The Preamble to the Declaration speaks of inherent dignity, the great worth of the person, as the basis of human rights, and declares these rights inalienable, meaning that they cannot be taken away by a decree or a denial. Article 1 states that all persons are equal in this dignity and that this dignity is linked to reason and conscience, long thought to be the features that set humans above other animals. Universal norms and entitlements, based on features that every human possesses—is this not natural law?

Natural law is more than one philosophy among many others. It is the actual, really existing, moral law that every person apprehends through one’s rational capacities. Many tenets of natural law take the form of prohibitions, such as those against murder, lying, torture, enslavement, bribery, stealing, preventing another’s speech, adultery, coercing another’s religion, and committing idolatry. Some take positive forms such as keeping one’s promises and providing safe working conditions. These obligations arise from the dignity of the human person, the goods that fulfill the person—life, bodily integrity, knowledge, religion—and prerogatives such as property that enable the pursuit of goods. Correlative to these obligations are the rights that recipients possess to dignity, goods, and prerogatives.

Human rights will be the cause not of Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, but instead of the Catholic Church, Nahdlatul Ulama (the world’s largest Islamic organization), Engaged Buddhism, and the World Jewish Congress.

Knowable through reason, these obligations and rights are universal. In C.S. Lewis’s book of 1943, The Abolition of Man, he adduces evidence that basic precepts of the natural law, or the Tao, as he calls it, exist across world religions and philosophies. Rights, too, exist widely across time and place. Contrary to the view that rights are inventions of early modern philosophers such as Hobbes and Locke, they find expression in the Bible and early Christian thinkers and are implicit in the concept of justice embedded in ancient Roman law and the thought of medieval philosopher Thomas Aquinas, the constant will to render another his due. Even where rights are not named, they exist correlatively to the universal moral law. These are natural rights, which are synonymous with what have come to be called human rights.

If human rights are not natural rights, what make them obligatory? What makes them efficacious? Can we expect them to remain robust in the years ahead? If human rights are not natural rights, they only can derive their efficacy from the fact that they are willed: declared, stipulated, contracted to, adhered to, advocated. If the rights are merely willed, though, then on what basis are people and states obliged to adhere to them? In the case of the treaties and organizations, states are obligated by their consent in signing and joining, but even this obligation—pacta sunt servanda—is a matter of natural law.

If rights are what is willed, then we cannot expect them to endure when mores and coalitions shift. They are the product of time and place. Yale historian Samuel Moyn describes human rights as rising and falling with parties and ideologies that favor these rights for ends other than the intrinsic validity of the rights. “A project of the Christian right,” he calls human rights in his book of 2015, Christian Human Rights, where he describes how, before the end of World War II, the Catholic Church championed human rights in opposition to secularism and communism and gave the world the modern human rights movement. When Christianity declined in the decades after World War II, parties of the left then took up human rights for their purposes. If we accept Moyn’s reasoning, we can conjecture that under different political configurations, human rights might evanesce altogether. If human rights are products of the will, their fate in turn will be determined by the power of those who will them versus those who do not. Ultimately the debate over the basis of human rights is a reprise of the one between justice and power that Plato described between Socrates and Thrasymachus in The Republic.

If the health of human rights in the world’s laws and institutions depends on a recognition of their status as natural law, this health faces dangers in the years ahead. Natural law has few adherents and many skeptics in Western universities, where human rights scholars, activists, and jurists are formed. Moyn is not atypical of scholars in regarding human rights as a product of politics. Even more damaging to the legitimacy and longevity of human rights are ardent assertions of rights that run contrary to the natural law. Human rights officials and activists widely promote the right to abortion—a right to violate another person’s right to life—and the right to “same-sex marriage,” flouting the natural idea of marriage between man and woman that virtually every civilization has held. Skepticism of particular human rights is growing, too. Legal scholars and philosophers in the West now argue widely that religious freedom—one of the most venerable of human rights, looked upon as a natural right by its proponents—merits no right of its own, either because it unfairly privileges religion among other forms of belief or because it is a Western idea backed by Western force. A world in which unnatural rights are asserted as human rights and in which natural rights are denied as human rights is one where the status of human rights will wax and wane with parties and ideologies, will, and power.

Seventy five years from now, if human rights still enjoy prominence, I predict that world religions—the keepers of the Tao—will be their greatest advocates. To be sure, world religions differ between one another and across their histories in their favor for human rights. It is they, though, whose commitments lead them to espouse universal moral norms that are based on human nature and human flourishing—the fundaments of natural law—ordered to a transcendent deity. Human rights will be the cause not of Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, but instead of the Catholic Church, Nahdlatul Ulama (the world’s largest Islamic organization), Engaged Buddhism, and the World Jewish Congress.