Statecraft Etched in Stone

Paul Edgar joins Rebecca Burgess to discuss the picture of statesmanship we can glean from an extended ancient inscription on a statue of Idrimi of Alalakh, discovered in 1939. Edgar has written on the Idrimi inscription for Classics of Strategy and Diplomacy.

Brian A. Smith:

Welcome to Liberty Law Talk. This podcast is a production of the online journal, Law & Liberty, and is hosted by our staff. Please visit us at lawliberty.org, and thank you for listening.

Rebecca Burgess:

Hello and welcome on this Groundhog Day to Liberty Law Talk, the podcast for Law and liberty. My name is Rebecca Burgess. I’m a Contributing Editor at Law & Liberty, Acting Director of the Classics of Strategy and Diplomacy Project, visiting fellow at the Independent Women’s Forum, and a few other professional odds and ends.

I mentioned Groundhog Day for its iconic Bill Murray movie reference, because when it comes to questions of statesmanship and international relations, the more we today want to describe everything as unprecedented, the more we find things are in fact very much precedented. On that theme, joining me today and highlighting the point, by talking about the Idrimi statue inscription, one of our most ancient accounts of statesmanship in near

Eastern history, perhaps the earliest complete biography of a political figure that has been discovered to date, is Paul Edgar of the Clement Center for National Security at the University of Texas, Austin. Welcome, Paul.

Paul Edgar:

Hi, Rebecca. Thanks very much for having me here, and thanks for your work on a number of things. We’ve had the opportunity, fortunate opportunity to work together on essays, and I’ve read your public writing frequently over the past several years, so thank you.

Rebecca Burgess:

Oh. Well, thank you. Well, I need to tell our listeners a bit about your honors and glories, Paul, on theme with our subject, and I promise I won’t be chiseling this in stone while we’re speaking. Paul is an Associate Director of the Clement Center, and he holds a Ph.D. in Middle Eastern languages and Cultures from the University of Texas. He’s also a philologist of several ancient languages and has studied, notably at Tel Aviv University.

But even more intriguing, before entering academia. Paul served more than 22 years as an Infantry Officer in the US Army, beginning as a platoon leader in Korea, and eventually finding his way to slightly sunnier pastures perhaps in Italy, hotter pastures in North Africa, and more recently serving in Iraq during Operation Iraqi Freedom, also in Afghanistan with his final assignment being in Jerusalem. Is that correct? I have that all right?

Paul Edgar:

Correct. Yeah.

Rebecca Burgess:

Perfect. So when I say that on today’s podcast we have a traveler from an antique land in the east, it is the truth. And Paul, I was wondering if you would mind if I did some personal indulgence and quoted Shelly’s poem that is on theme?

Paul Edgar:

Sure. No, no. That’s a great idea.

Rebecca Burgess:

Oh, great… So, “I met a traveler from an antique land, who said, “Two vast and trunkless legs of stone stand in the desert … Near them, on the sand, Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown, And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command, Tell that its sculptor well those passions read. Which yet survived, stamped on these lifeless things, The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed; And on the pedestal, these words appear: My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings; Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair! Nothing besides remains. Round the decay of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare. The lone and level sand stretch far away.”

So of course, as you know Paul, that’s Shelly talking about Ozymandias, the Pharaoh. But speaking of words on pedestals, I wonder if you can start us off by telling us about how important these old statues and inscriptions are, how they keep on ending up in British museums and us finding them in British museums and studying them there, how Shelly was responding that too in his day, but today, why relatively recently we’ve only come to the history and the knowledge of this statue?

Paul Edgar:

Well, I find these things interesting. And I think they’re academically important. I think they can certainly enrich what we already understand classically and practically about politics, politics broadly. Most of what I’ll talk about today is international politics, but international diplomacy. So I don’t think they offer anything new, but I think they do offer confirmations of these things that we know more traditionally from the era of Herodotus and Thucydides and forward. I think historically our understanding of history and political history especially begins there, right around the 5th century or 6th century B.C. You could turn, I say, perhaps we could turn to some biblical text, but for the past couple 100 years at least, people have been hesitant to do that, certainly the last 100, 150 years. But our understanding of these things begins with those texts that remained with us from the time they were written all the way through today.

And Napoleon, I’m sure many other things involved, but Napoleon’s tour, I think the whole tour was unexpected. He went to Egypt and then got stranded there in Egypt and thus worked his way up the coast of Palestine, Syria. But when he did that, one of the things that occurred, or one of the things that corresponded with it was this sensation in Western Europe with things that are older, things that we would call pre-class, that predate Herodotus and Thucydides. And so, there was a rush of archeological exploration, much of that private, privately funded, or perhaps a kind of a combination, private and state-funded. But there was a whole lot of private involvement, private money involved. And as a consequence, we discovered so much. We discovered Sumerian texts and Acadian texts, thousands of years of these things. Much of that is what we would call accidental. In other words, we may have stumbled upon archives, formal archives, but our discovery of it isn’t complete. We happen to find particular archives for different reasons, perhaps the ones that were easiest to find at the time. And there’s probably still a lot more that we still don’t know about ’cause it’s all been covered up.

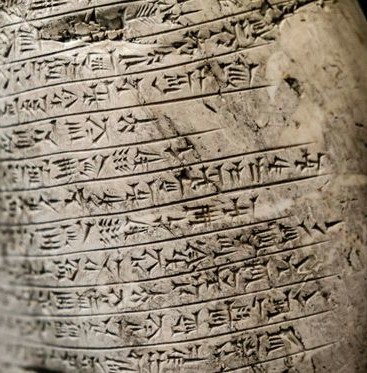

But anyway, so we discover this material. A lot of it is cuneiform tablets. Most of those tablets would be receipts, but a whole lot of them, our diplomatic texts, they’re diplomatic letters, they’re treaties. And over the last 200, 150, 200 years, academics have had an opportunity to, one, sort of crack the code. ‘Cause most of these languages we didn’t know. We didn’t even know they existed. So we had to decipher the script, decipher the language, and then organize the language and better understand it. And all of that, of course, takes a long time, for a number of reasons.

But I think we’re in a position now where we can take a lot of those texts and tell a bigger story, tell a more complete story of the eras that we would consider early iron. So this is much of what is captured in the early part of the Hebrew Bible and Samuel, Kings. But then much earlier than that, and the example today comes from what we call the late Bronze Age, an era from about 1,600 to 1,200 or 1,100 B.C. And the statue that we’re talking about is kind of towards the latter end of that in the 15th century, about 1,450 B.C.

Rebecca Burgess:

So who would, for context for some of our listeners, who would’ve been the big figures? Egypt comes to mind, of course, lots of people know some of the pharaohs, around which Pharaohs or reign would this might have been?

Paul Edgar:

So, I’m a little hesitant to… Sometimes I’m hesitant to talk super precisely, but in this case, I think we’re at least fairly safe to say, or we’re certainly safe to say that the prominent Egyptian pharaoh during Idrimi’s rule, again, we’ll introduce Idrimi a little bit more or in more detail here shortly, but during Idrimi’s rule, the two pharaohs that would’ve been in power were probably Thutmose III and Amenhotep II. Both of whom, mainly Thutmose III, but both of them conducted military expeditions up into this area. Now those tended to be short-lived, they didn’t establish, they didn’t colonize, or try to annex anything up there, but there were certainly prominent military expeditions up there. So, they did reach the area of Idrimi and certainly would’ve been known to Idrimi and those that he socialized with.

Rebecca Burgess:

Got it. So speaking in a mix of both biblical peoples and terms and modern day, we’re talking about, with Idrimi, the area of modern Turkey, Syria-

Paul Edgar:

Right.

Rebecca Burgess:

… the Canaanites, right? Am I getting that right? That’s about where it?

Paul Edgar:

Yeah. Yeah. No, that’s more than fair. So, where Idrimi’s statue was found and where Alalakh, his city or city-state was located is in modern Turkey, but it’s barely in modern Turkey. It’s just on the other side of the Orontes River there near Syria. I would still refer to it as Syria. I know that some, depending on how people conceive of these places, some people may disagree with me or even disagree with me sharply. But I consider this northern Syria, not in the sense of the modern state, but geographically.

Rebecca Burgess:

Got it. Got it. And then, this particular statue was found somewhere around the 1930s, correct?

Paul Edgar:

Right. So it was a British expedition. Leonard Woolley, who was now, wouldn’t be considered a modern or a high-tech archeologist in our day. Archeology has come a long, long way in the past couple of 100 years. They’re still coming along, they have a long way to, but they’ve come a long way. But for his time, Woolley was very precise about what he was doing. He had certain methodologies of controlling a dig and being very methodological about it, and accounting for where, how things were found, and the state it was found in. He did that as well, or better than anybody who had preceded him.

Rebecca Burgess:

So I think, when you first brought this topic to my attention, what I was most, maybe arrested by is, speaking as a political theorist, we often get a little caught up in the words in texts and thinking about learning actual political theory in a sense, but politics and diplomacy from a statue and an inscription on a statue, I found absolutely breathtaking, but also fascinating. And the physical statue itself is very intriguing and unique. Could you describe a little bit about it? From my understanding, the writing is actually on parts of the body of the king. And even with a little thought or speech bubble coming out of one side of his mouth.

Paul Edgar:

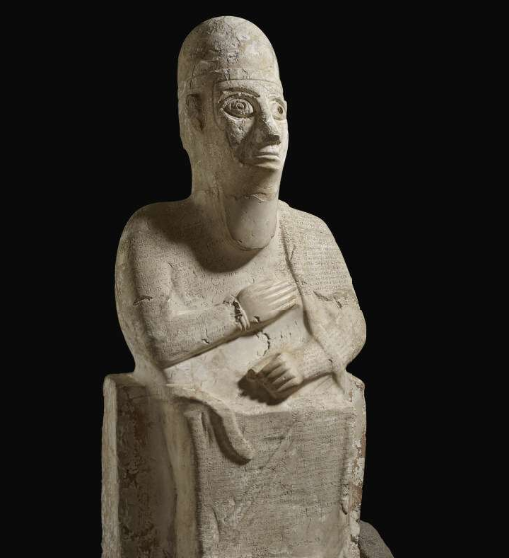

Correct. So the statue, and anybody can look this up, you can look this up on Wikipedia, there’s a really nice picture of Idrimi and the inscription on Wikipedia. The British Museum, of course, has a couple of good photos as well. But actually, those photos are a little bit without context, ’cause they have a black background, and so you think it might be huge. And it’s not, it’s three and a half feet tall, and it’s made of, I may be mispronouncing it, but I think I’m using the right term, magnesite. So this is a light, perhaps a light gray or a white stone, at least two pieces, the throne and then Idrimi, the figure of Idrimi himself are two separate pieces. There may be more than that, but certainly two primary pieces. And then the inscription, which is in cuneiform form, in a language that we normally refer to as peripheral Acadian, is written across the statue and begins in one spot, and they use about all of the, not all, but most of the surface area of the statue to write this inscription, which again, is, in summary, a political biography of Idrimi’s life.

Rebecca Burgess:

Great. And of course, the king himself could have inscribed this, but we actually know that it was not himself, it was a scribe, correct-

Paul Edgar:

Right.

Rebecca Burgess:

… who actually wrote it?

Paul Edgar:

Yeah. The scribe mentions himself twice in the inscription and mentions one of Idrimi’s sons in the inscription as well. So I think it’s fair to say, unless we learned something else later, I think it’s fair to say that this inscription was written by his family and political colleagues or servants shortly after his death. The end of the inscription is essentially an epitaph that is very, very formulaic, often found on the tombs of royalty at the time. So, while Woolley found this, it was not set, it doesn’t appear to have been set near Idrimi’s tomb, but it may have been set near where he was buried originally, or certainly, it was at the very least sculpted and then inscribed on in order to commemorate his life after he had died.

Rebecca Burgess:

Got it. Well, maybe we should turn to that life now, and you can tell us a little bit about who this enigmatic and clearly charismatic individual was, I think. And we’ll get to, of course, feel free to actually invoke the inscription, which you have translated in an original translation. But he mentions that, oh, his older brothers didn’t quite get the political situation, but he, the younger brother did. So anyway, he seems like a little bit of a character, so feel free to tell us a little bit about him.

Paul Edgar:

According to this inscription, his biography, and we imagine that certainly there was a lot more involved, and the biography is also uniformly positive. So there were probably some rough points, and Idrimi probably had some rough points, even if he was a fantastic leader. There were probably some failures, which the inscription does not capture. So with those as maybe some disclaimers, it’s fair to say that a summary of his life, he begins his life, his family lives in Aleppo, so this is Syria proper. There’s no argument. It’s not whether it’s Syria or Southeastern Turkey, but his family is in Aleppo. And for a number of different reasons, we believe that it’s a prominent family. It may have been the most prominent family. His father may have ruled in Aleppo. The inscription hints that he probably did, but something bad happens, and we’re not sure what. I translate it as a calamity. But in short, the word words mean a bad thing happened.

Rebecca Burgess:

Right.

Paul Edgar:

So something bad happened to his family in Aleppo, and they fled to Emar, which was just about 50 miles to the east of Aleppo. And Emar is a famous archeological dig today with lots of Akkadian texts. So they lived in Emar, where his mother was from, and it appears that everybody was content. Perhaps they were still disappointed with whatever happened in Aleppo, but they were sufficiently content to stay in Emar, except for Idrimi, who, as he grew older, became more and more incensed at what had happened and thought that it was his job to sort of reestablish the family name and family rule in some sense. And in order to do that, he leaves Emar. He goes south into Canaan, which we would consider probably somewhere near the northeastern border of modern Lebanon with Syria today, somewhere in that area.

He runs into a number of refugees from Aleppo that recognized him and knew of his father. He stays there, and just sort of consolidates power or waits for the right moment, sails up the coast with some soldiers, and then sails north, probably about a hundred miles up the coast, probably crosses what would be the mouth of the Orontes River there in the northern Mediterranean. He disembarks and finds more people, apparently, that recognize him, and he sets up in a town that in English we’ll just call Alalah. And as I mentioned, that is right there about a mile away from the current Syrian border on or near the Orontes River, so where Syria, the Orontes, and Turkey sort of meet, right about there. And that’s about 50 miles to the west of Aleppo. So Idrimi did not travel more than about 100 or perhaps at the most, 150 miles from his birthplace of Aleppo.

So he successfully sets up in Alalah with what I’m going to call a domestic constituency, but that’s not enough. He needs to also gain support from one of the great powers, and in this case, the correct sort of candidate, the best ally to make amongst the great powers was Mitanni, the kingdom of Mitanni, which Mitanni is roughly analogous to what we might consider today is Kurdistan, right?

Rebecca Burgess:

Got it.

Paul Edgar:

If we drew borders for Kurdistan, it would be right about where Mitanni is located. The other great power, so we mentioned Egypt, Mitanni is the second, and the third would be Hatti. The Hittites, I think many people are more familiar with that name, the Hittites, the people of Hatti, which was largely in modern-day Turkey. So those were the three powers that he could have relied on and he chose to try to make peace with Mitanni, is successful, and then he also has to defend against some other local rulers. He is successful and, again, sort of consolidates power after that and seems to have a successful period of rule.

Rebecca Burgess:

This doesn’t sound at all familiar to more recent events in the Middle East. Regional powers, fights for powers, families, and tribal societies.

Paul Edgar:

Right. Now, I said that was a summary, but that was probably more than a summary. I apologize.

Rebecca Burgess:

Yeah. No, no, that’s really helpful. I mean, it’s fascinating, and I know you’ll probably read some from your translation, but just the opening, “I am Idrimi, the son of Ilim Ilimma,” if I sang that right, “the servant of the storm god, Hepat and Ishtar, this lady of Aleppo, my lady.” I think it’s fascinating, this kind of chronology that he brings in. But then also this question of the gods and from our Thucydides Herodotus and everyone where we’re so familiar with this question of how do we ground political power and how does a king ground it with his people?

Paul Edgar:

Right. This is a great question. This is a really great question, and I think sometimes our answers are too narrow. For example, when we look at the Hebrew Bible, if you look at the Hebrew Bible, there’s a lot involved, but on the surface, we tend to summarize it as if Yahweh approves of a leader, then the leader is approved and successful, and well, that would certainly be true. It wouldn’t be the only thing that’s true. There’s a lot of work that goes into political leadership, both good and bad examples of political leadership. There’s more than simply a supernatural stamp of approval. And we see this in Herodotus. One of the things, the first time that I read Herodotus, what really occurred to me is how infrequently he refers to a kind of divine providence or divine approval, right?

Rebecca Burgess:

Right.

Paul Edgar:

It comes up here and there, but lots of other things come up as well. And I think that’s what we’re seeing here. We see in one part an appeal to divine authority, but then you see somebody who’s really rolled up his sleeves and done the hard work of leadership as well. And I want to say, I guess I should caveat that a little bit and say, I don’t know whether Idrimi was tyrannical or was magnanimous or what, I don’t know. But either way, the fact is that political leadership is hard work, and he apparently put in that hard work in order to be somewhat successful.

Rebecca Burgess:

Right. He mentioned seven years where he released birds, and inspected lambs. He is waiting for apparently auspicious signs, but that he also mentions, and then he built ships, and he gathered soldiers and he kind of networked it sounded like, to get more soldiers and to impress his older brothers, so his family or his tribe. And then as often happens in movements, success breeds success, almost. And it seems like the more people come the more successful he is. I mean, correct me if I’m wrong, but it almost seemed like to actually reestablish his city, he relied mostly on the recognition of the king of Mitanni.

Paul Edgar:

Right. So let’s do this. I’ll read an excerpt that sort of captures-

Rebecca Burgess:

Yes, perfect.

Paul Edgar:

… this, what I’ll call the domestic constituency or part of it. And then we’ll read a part that, this seven years that you referred to, I’ll read that part and we can comment on both of those. So we’ll start with line 27. So this will cover his period in Canaan amongst the Habiru, which, if we have time we can talk about whether or not that is related to the word Hebrew. But it’s an interesting and divisive question. Anyways, this captures his period in Canaan and then his sailing up the coast and establishing his initial rule, at least in Alalah. So lines 27 through 42. And I’m not sure if you decide you want to link the article where I translated this, and I’m not trying to pump up my article, but if it’s helpful for listeners, then they can refer to it.

Okay. So “I settled in the company of the Habiru for a long time, for seven years. I released birds, I inspected lambs. Then in seven years’ time, the storm god returned to me, so I built ships.” And let me pause here. So to me, this is really interesting, and I won’t comment on this at length, but those of us that are involved in either studying or actually as a practitioner in some sort of political or military leadership, we are always looking for certainty, right?

Rebecca Burgess:

Right.

Paul Edgar:

We want to know that what it is we’re doing is right, whether in a moral sense or practical sense, that this is actually going to work. And while Idrimi’s search or search for certainty, we might consider more rudimentary than ours, he’s inspecting the entrails of lambs or the kidneys of lambs and releasing birds, it’s still the same sort of activity, this quest for certainty in political leadership and decision making.

Okay, so picking up again, “I loaded formations of nullu soldiers,” and just as a comment, we don’t know what nullu is. It’s a special type of soldier, but we’re not sure what, but he loaded soldiers onto ships. “I approached the land of the Mukishim by way of the sea,” so he is sailing up the Mediterranean coast, “and I arrived on dry land in front of the Hazi mountains. I went up and my land heard me. They brought goats and sheep before me. And within one day, as one person, the people of the land of Nihi and Amaae and the land of Mukish and the city of Alalakh, my city,” at least subsequently it becomes a city, “they had turned to me.” So I’ll pause there.

So there’s an earlier passage that captures an earlier part of his, again, what I’m calling a domestic constituency. And here is part of where it grows and is more formally established, and its legitimacy, at least internally, internal to this particular political body, seems to be firm, seems to be established. Of course, his legitimacy in the eyes of others who are relevant is an open question. So we’ll move on to that next. So the next section I’ll read comes from lines 43 through 60. And this is where Idrimi essentially seeks the approval, the acceptance of the king of Mitanni who here is, whose name is Parattarna. We actually have evidence of Parattarna from other sources.

We also have, so your listeners know, we have evidence of Idrimi from other sources as well. So we have a lot of confidence that we’re not talking about Hercules or Aries or anything like that. This was a real person and a real political figure, and so was Parattarna, the king of Mitanni. Now, in the text, it actually refers to him as the king of the armies of the Hurrians. But for our purposes, the king of the armies of the Hurrians and the king of Mitanni are one and the same. Okay. So, “Moreover, for seven years, Parattarna, the strong king, the king of the armies of the Hurrians, made an enemy of me. In the seventh year, I wrote to Parattarna the king, the king of Ummanmanda, and I spoke about the services of my fathers when my fathers found relief before them, the Hurrians, and about our other affairs concerning the kings of the armies of the Hurrians, and it was good. Thus, they established between them a strong oath. Right now, he’s referring to, whether it’s fictive or whether it’s real I don’t know, but a previous relationship between his people, presumably his father, and the people of Mitanni.

Rebecca Burgess:

Just a slight pause here, if I’m getting it right. He starts out kind of as an enemy, right, of Parrattarna?

Paul Edgar:

Right.

Rebecca Burgess:

And something happens where they’re able to establish it’s either a draw, maybe a military draw?

Paul Edgar:

Well, I doubt it’s a military draw.

Rebecca Burgess:

Yeah, probably.

Paul Edgar:

What I anticipate is that, and I’m a hundred percent, this is supposition. I think it’s an educated supposition, of course. But I anticipate that Parrattarna conducted annual military expeditions and that some of them would’ve gone near or through Alalakh.

Rebecca Burgess:

Got it.

Paul Edgar:

And perhaps as this new upstart city state or king over a city-state that had existed prior, Parrattarna did not immediately accept his kingship. And perhaps for many reasons, either lack of interest, lack of time, or other priorities, didn’t just smash him. I anticipate that the kingdom of Mitanni would’ve had no problem smashing Alalakh had it wanted to. But in any case, they were at enmity with one another, or at least Parrattarna was towards Idrimi. And after a period of time, it says seven years, and I think that it could be exactly seven years or this could be sort of a trope in that over this arduous complete period of time where I was working to establish relations, finally, my appeal got through to Parrattarna, and he realized the great wisdom of it and accepted me, and then he made me king. I mean, that’s what he says, is that in fact he doesn’t really refer to himself as a king until Parrattarna, the king of Mitanni, accepts him or acknowledges him as king.

He refers to this prior relationship, and let’s just sort of take that at face value, is it’s an appeal to history, right?

Rebecca Burgess:

Right?

Paul Edgar:

Perhaps it’s true history too, but it’s an appeal to history that, hey, we had great relations before. Now I was in Aleppo, or my family was in Aleppo, not Alalakh, but we had great relations before, so why don’t we pick up where we left off there, and apparently it was convincing. The strong king listens to what I said about the services of my predecessors and the oath that was between them, and he respected the oath, he received my greeting gift for the sake of the matter of the oath, and for the sake of our services, a lost house, in other words, Idrimi’s house, returned to him. Now the domestic constituency is supportive. The great power of the region, or perhaps the most relevant great power of the region, is supportive. You’d think that that would be sufficient, but it’s not. But wait, there’s more.

Rebecca Burgess:

Never enough, exactly. Yes. Oh, I love that next line. It just says, they piled up my ancestors upon the ground so I piled up theirs upon the ground. In battle, I piled them high.

Paul Edgar:

Right. So I ended with a lost house returned to him. Right?

Rebecca Burgess:

Mm-hmm.

Paul Edgar:

Just two or three sentences later, this actually, he then has to fight in order to defend his kingship from those around him. I spoke to him regarding my case, so he is still talking again about Mitanni, and regarding my loyalty, and then I was king. This is the first time that he pronounces himself as, or mentions himself as, a king. The very next sentence, “The kings to my right and my left rose up against me against Alalakh, for he had made me equal like them.” They attack him because they don’t want another peer. Right? They preferred it when Idrimi was not a king recognized by Mitanni. Somehow this is a threat. Perhaps it’s a threat because they’re allied with somebody else or it’s just a threat because they’re allied with Mitanni and less of Parrattarna’s attention if there’s another vassal king to demand attention and resources or whatever else.

This part of my translation I have taken from a former professor of mine, a mentor of mine, Ed Greenstein, the scholar who co-wrote the article with him, and is from the early seventies, this translation, David Marcus. We don’t know what these next lines say. It’s very difficult to translate for a number of reasons. But I thought that Greenstein and Marcus did a really great job of understanding the material of the era, what kind of material literature of the ancient near East would’ve been consistent with this, and essentially cut and paste material actually from the Hebrew Bible that they think captures what these words or what these lines probably say, something along those lines. But I think it does at least capture the intensity of the fight between Alalakh and the kings around them. “Just as they piled up my ancestors upon the ground, so I piled theirs upon the ground, and in battle, I piled them high.”

Idrimi Has to defend himself against the small powers around him. Only once he’s done that, so he’s now established a domestic constituency that is stable, he’s established a relationship with a great power that is stable, and then he battles his neighbors until they leave him alone and are convinced that, okay, either we accept him because he is proven himself, or we can’t overcome him, or the cost of overcoming him is too great, and so we’re going to stop here and call it good. And then he can relax a little bit.

Rebecca Burgess:

Right. Right, where he mentions that he had an estate built. Finally, after all of his enemies are at least neutralized, he had an estate, so he made his throne like the throne of kings and built up his city essentially. I thoroughly enjoy the kind of listing of duties than of what he needs to do as a good king. Or we might imagine him or his scribe saying here’s how and why he was a good king. He settled the inhabitants, he says. In that next part, those lines, 81 and 91, he established the lands. He made my cities equal to those that came before me. Then there’s once again, the establishment of cults of religion, of the gods of Alalakh, and then prayers and offerings. There’s kind of this, as there was at the beginning, a throwback or a recall of tradition and religion and the gods. And then he says he passes it to the hand of his son, so he kind of gives through the narrative of succession. I don’t know, is there anything about that that particularly caught your attention?

Paul Edgar:

Well, there’s two things, the two big things that stand out to me in these next couple of paragraphs. You’ve mentioned one of them, what we might call the stability of the international system, enables him, provides him the bandwidth to do these domestic, these kinds of necessary domestic tasks of improving the lot of his people. That’s maybe the best way to capture it, improving the lot of his people. He refers to essentially settling those that came with him, settling or improving the prosperity of those who already lived there. And then there’s a kind of an oblique reference to settling those who had not been settled. In other words, if you imagine this may be a little bit of a stretch, okay, so bear with me on this, but if you imagine that the prosperity is so great that of course due to Idrimi’s greatness and great leadership, that even those who were previously homeless suddenly had a home, that they were settled.

Think of it in those terms. And then again, that may be a little bit of a stretch, that these people who were not settled could have been either migrants or nomads, people who were intentionally moving from place to place because that just was their way of life. But in some way, people who had not yet settled, settled because of the prosperity and stability that he brought to that region. That stands out.

But then another, and this is worth looking at briefly is line 64. “I took an army and I went up against the land of Hatti, and I seized seven cities.” And he named those cities. He seized those cities, and he destroyed other ones, “And the land of Hatti did not assemble or come before me, so I did what I wanted.” I’ll read one more sentence. “I took them captive. I took their property, their goods, their pilferable things. I divided it for the army, my auxiliaries, my brothers, and my friends.”

If you are a friend of Mitanni, you’re automatically an enemy of Hatti, and this passage makes him sound very bold. And perhaps he was, perhaps he was. My guess is that these were really, really minor incursions to an area that might be kind of minorly considered Hittite. Because again, if just like Mitanni could have wiped out Alalakh at any minute, any time they wanted, well, Hatti’s relative power right now is sort of a little bit reduced from what it was previously and what it will be in another 50 years or so. Hatti still could have wiped out Alalakh without much of a problem.

But essentially, he’s demonstrating his loyalty to Mitanni. This is some bravado here and some bragging about himself, but it also does help place him, again, in what we would call the international system of the era. He’s aligned with one and against another and actually takes military action against the enemy of the king that supports him.

Rebecca Burgess:

Right, and kind of showing us in, so to speak, real time the balancing and the tensions and the dynamics at play in keeping, you’ve mentioned the three constituencies, but really that larger, kind of we go up another level to look down on the situation of how anytime statesmen, kings, are thinking about keeping their people and their kingdom safe, they have to think about all of the different pressures from outside and how they balance those things. You had mentioned certainty and the great desire for certainty and the real lack of it in the international system and how this is what we see. You know? Yeah.

Paul Edgar:

Stable does not mean fixed, right? Stable means stable enough, but it’s always changing, and in a sense, it’s always hanging by a thread. Right? Even a stable, strong international system is arguably hanging by a thread, and if that thread breaks, and of course, I’m speaking to you here as a conservative, one who would argue generally for stability rather than rapid change, if that thread of stability breaks, the amount of suffering by everybody, by all classes and all people and all races, the amount of suffering is absolutely immense.

Rebecca Burgess:

There’s a real role it seems to me in this inscription for agency and understanding how Idrimi himself thought about that and what we can learn from it. I mean, in the essay that we keep on referring to, and I’ll mention it again at the end, which you wrote about this inscription, you mentioned that Idrimi shows that circumstances are not determinative, and neither is geography because Idrimi started out in one situation, he fell from whatever that was to a really bad situation, and somehow managed to be in a better place with supposedly a line of succession after him strong enough that he could curse on his stone anyone who dared to move it, but then also blesses anyone who read it and prayed on his behalf. I think that agency is really interesting, especially when we think of, today, how we look at international relations, foreign policy, and even diplomacy and statesmanship.

Paul Edgar:

Right. And there are a few things this makes me think of, and I’ll try to riff off that thought.

Thinking about Idrimi himself, my dissertation is about this whole era, the political history of this whole era, and so I’ve read tons of treaties and diplomatic letters. Primarily those are between a great power, either Hatti, Mitanni, or Egypt, and a small power, a town or a city-state like Alalakh, or Aleppo or Ugarit which is on the coast of Syria today, within Alawite Syria. And lots of other examples. Jerusalem, right? Jerusalem, pre-Israelite Jerusalem, there are letters from the ruler of Jerusalem to the Pharaoh of the era.

So having read all of these things, the agreements and the treaties, those formal treaties and what we might consider informal treaties, just arrangements that are not written, for each of the small powers, there are similarities, of course, there are similarities, but there are also really prominent differences. In other words, there was negotiating room, and there was room to maneuver, politically speaking. And when a great power was breathing down your neck, even breathing down your neck demanding that you become a vassal, when you agreed to that, there was still some negotiating room so that your particular treaty with that great power might be more or less onerous or provide for more or less liberty, for your own rule for your people, et cetera.

So there is agency within circumstances, within the systematic forces that compel small powers or great power… Whoever. But usually, we’re referring to small powers. The political forces in action force small powers to do whatever. Usually, it’s something negative or bad. And there’s some truth to that. I don’t want to say that political forces don’t exist. But those political forces, as well as the decisions made by rulers of small powers, are decisions made by human beings. Because of that, this is not a physical tsunami that has no capacity to change course, it is headed for its target, and it’s just going to crush it. Because these are decisions made by human beings, there naturally is room for differences, for negotiation, for agency, for room to do things a little bit differently.

I think that does come out, not just in this text, but in the political history of this whole era.

Rebecca Burgess:

It’s a little irreverent of me to say, but Francis Fukuyama’s end of history would not have quite worked at this point, would it have? So much history before them, right?

But on that note, for me, what I found so valuable amongst many things of your scholarship about this is just seeing how this one inscription, this one statue, gives us a snapshot in time of one moment in a protracted regional struggle, or a struggle for regional hegemony in this particular area, in a situation in which you did have three larger powers, Egypt, Hatti, and Mitanni. And how, clearly they’re not robber barons, but littler kings managed and maneuvered within that, and how close that feels to us today, but also how the themes…

In reading this inscription, I get a little bit of Machiavelli, what is it that always motivates the sons when their patrimony is taken away? But not everyone is. Idrimi is, but his brothers aren’t. But then you have this question of the gods, which we mentioned, and tradition. The question of what is it that makes a good king and political legitimacy, your own people looking at you or not? But then… And I think you mentioned this at the beginning, and maybe as we end or wrap up, which sadly I guess we have to do, there’s so much to say, is what is the other value of this text?

Just as a classic source, you could say, I think there’s something that you’ve mentioned before about it because it’s not Thucydides because it’s before Thucydides and doesn’t have the weight of all the commentary around that, perhaps it helps us clarify some things. But then when we think, say, to today’s practitioners and students, what might be one or two things you would love for them to think about in looking at this text?

Paul Edgar:

I think there are a number of things, but let me go with this because based on a question someone asked me yesterday, I started thinking about this. Now I don’t want to draw too much of a parallel between Syria then and Syria now, but I think there are some things that we can at least discuss.

Somebody asked me yesterday, why President Assad is failing where Idrimi, in the same region, not all of Syria, but in the same region, appears to have been successful. And you don’t pick up a lot of humility from Idrimi from his inscription, but I think reading between the lines, this is somebody who was willing to compromise, willing to recognize that he couldn’t have everything that he wanted. And since he couldn’t have everything… This is Machiavelli, right? Don’t go for the ideal. It’s in that sense, it’s Machiavellian. Don’t pursue the ideal if it doesn’t work. Pursue what will work. And because it works, then in this sense, the state has its own morality.

Now, I know some Machiavelli scholars may not like my use of that. I think it’s true, I think it’s part of what he’s saying. He says more than that. But I would say that Idrimi, in his willingness to compromise with Barattarna, knowing that he couldn’t be a king without the recognition of a great power, was willing to give up what might have been his ideal situation to establish something that actually worked. Not just for him, but for those around him. And we could say that Assad is doing exactly not that. Now, Assad certainly has the support of a mediocre power, but he’s not recognizing all of the legitimate political equities within, heck, I’ll say it now, what was really formerly the state of Syria.

And if he had at some point… preferably much earlier than today, but if he had at some point recognized that there’s some legitimacy here that others have or legitimate concerns and that if he could imagine that whatever his ideal is is not going to come to fruition, and be willing to explore the space in between and what might be a reasonable settlement… Now I know that’s a lot to claim or demand from him in an area like that, but that’s the leader’s responsibility, right? That’s the leader’s responsibility. That’s the J-O-B.

Rebecca Burgess:

Right.

Paul Edgar:

But he’s not willing to do it, and so as a result, he’s impoverished from it, and everybody around him is impoverished from it. And impoverished doesn’t really capture it. Calamity doesn’t capture it, right? It’s many calamities put together.

Rebecca Burgess:

Right.

Paul Edgar:

But I think that’s one of those things that we could say that we get a little bit from Machiavelli or we see from Machiavelli in his political theory, but then we could say we see it in practice as well. So this is an example of what I would consider, okay, well this is something that we could point at and say, “This is a classical characteristic of good political leadership or successful political leadership.” Because we don’t just see it because Machiavelli projects it upon our society from the 15th century CE forward, but we see it in a text that predates him, that predates all of the Greek political philosophers and political historians. So it’s a reinforcement, right? It’s not teaching us something new, it’s simply reinforcing things that we ought to know already.

Rebecca Burgess:

Do you think that it’s in that vein… Really, really wrapping up. Do you think it’s in that vein of teaching and transmitting to future generations these themes of what it takes, what’s at stake, of statesmanship and caring for our people, that Idrimi included that?

And I know there are tropes of this, but what’s so fascinating, at the end of his statue he invokes blessings and curses. “Whoever tears down this statue of mine, may his descendants be subdued, may heaven curse his name, may the underworld take his descendants.” It goes on. But then also, “May the gods of heaven and earth cause the scribe who wrote this to live, guard him, be good to him.” And then, “May those who read this and look on this,” the words, “may they pray on my behalf.” And I wonder if this is really early recognition of the importance of transmitting the lessons of kingship and statesmanship.

Paul Edgar:

I think so. I think there’s certainly some hubris there, right? “Remember me.” But also it’s more than that. It’s more than that. And even there have actually been some scholars that have done a little bit of work on that. Actually, one of the mistakes that scholars sometimes make with this particular text is that they look at it and they pick out one single thing that to them is the most important and say, “This is why Idrimi wrote this,” or, “This is why his political colleagues and family wrote this.” It’s probably for a whole bunch of reasons. But this certainly is one of them, that there would be some kind of continuity. That there would be a going forward and not simply a reversal of political stability.

Now again, I don’t want to say whether he was a tyrant or not, because sometimes political stability is worth shattering. But if you shatter it, make sure you know exactly what you’re doing. More often than not, I think it’s this idea of communicating the value of what has been done, what has been established, and not reversing it or not undoing it, because your perspective from things at this moment may be very different than the other side of chaos.

Rebecca Burgess:

Right. Well, hopefully, this podcast has not been chaos or chaotic for our listeners. But thank you again, Paul, for your insights and scholarship on both statesmanship ancient and relevant to today, but also the Idrimi statue inscription. It’s not something I think many of our listeners or many within political theory know about, and it’s definitely worthwhile as an example of the real physical object speaking both through space and time, more than the Ozymandias statue perhaps.

So once again, thank you. That was Paul Edgar, who is the Associate Director of the William P. Clements Jr. Center for National Security at the University of Texas, Austin, and I am Rebecca Burgess, a Contributing Editor at Law and Liberty, and this is Liberty Law Talk. Many thanks to all our listeners.

Paul Edgar:

Thanks very much.

Brian A. Smith:

Thank you for listening to another episode of Liberty Law Talk. Be sure to follow us on Spotify, Apple, or wherever you get your podcasts, and please visit our journal at lawliberty.org.