The Inalienable Right to Religious Liberty

Vincent Phillip Muñoz joins host Samuel Gregg to discuss his new book, Religious Liberty and the American Founding: Natural Rights and the Original Meanings of the First Amendment Religion Clauses.

Brian A. Smith:

Welcome to Liberty Law Talk. This podcast is a production of the online journal, Law & Liberty, and hosted by our staff. Please visit us at lawliberty.org and thank you for listening.

Samuel Gregg:

Welcome to Liberty Law Talk. My name is Sam Greg and I’m distinguished Fellow in political economy at the American Institute for Economic Research, and I’m also a contributing editor at Law and Liberty, part of the Liberty Fund Network. Thanks for joining us today. Religion and religious liberty seem to be major points of contention today across the United States. Whether the issue is school prayer, religious exemptions from healthcare mandates, or the degree to which legislators, even presidents allow their faith to shape politics and policies. It’s very hard to escape debates about the place of religion in the public square today. Overshadowing all this is the fact that a concern for religious liberty was at the forefront of the minds of many American founders. This was eventually given expression in the First Amendment, but what did the founders really think about religious liberty? Did they think of it as a natural right and therefore connected in some way to natural law, or was the securing of religious liberty essentially focused on securing social peace?

These and many other questions are discussed in a new book entitled Religious Liberty and the American Founding: Natural Rights and the Original Meanings of the First Amendment Religion Clauses published by the University of Chicago Press. I’m very happy to be joined today on Liberty Law Talk by its author, Professor Vincent Phillip Muñoz. Professor Muñoz is the top field associate professor of political science and concurrent associate professor of law at the University of Notre Dame. He’s the founding director of Notre Dame Center for Citizenship and Constitutional Government. His scholarship has been cited multiple times in church-state Supreme Court opinions most recently by Justice Alito in Fulton V City of Philadelphia 2021, and by both Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Thomas in Espinoza V Montana 2020. He’s widely published having written several academic books as well as articles on topics like religious liberty, the idea of natural rights, as well as the American founding. He received his BA at Claremont McKenna College, his MA at Boston College and his PhD at Claremont Graduate School. Philip, welcome to Liberty Law talk.

Vincent Phillip Muñoz:

Thanks for having me.

Samuel Gregg:

Today in America, Philip, we often think that it’s hard to imagine a topic more controversial than religion and religious liberty. I suppose that’s because religious liberty touches on questions ranging from Constitutional interpretation to the more generic place of religion in American society. Now you’ve been writing about the nature of religious liberty, its connection to ideas about natural rights as well as its Constitutional and wider political implications for many years. So tell me this, why did you decide to write this book at this particular time?

Vincent Phillip Muñoz:

Yeah, that’s a good question. Thanks again for having me on. I’m a fan of the show and listen to it regularly, so it’s a pleasure and a treat for me to be on it. Why did I write the book? Well, I suppose I thought, every author thinks, that I saw something or see something that others don’t see, and I think that’s the natural rights foundations of religious liberty in American constitutionalism. In our jurisprudence and in the scholarship, people don’t talk about natural rights that much. And I think by ignoring natural rights, because we don’t really understand natural rights, we don’t really understand the founder’s thinking. And I think that leads to misinterpretations of the First Amendment.

Samuel Gregg:

Now, I noticed in the title of your book, or more precisely let’s say the subtitle, that used the word words, the original meanings of the First Amendment religion clauses. So not original meaning in the singular but rather original meanings in the plural. Now I take it that you are indicating here that to speak of original meaning in a singular sense is somewhat of a mistake. Am I right in supposing that or did you have something else in mind?

Vincent Phillip Muñoz:

Yeah, no, I think that’s exactly right. I think there are a different meaning for the establishment clause and the free exercise clause, but it’s even more complicated than that. One of the chapters in the book, I think it’s the four chapter is titled something like “How the Founders Agreed about Religious Liberty but Disagreed About the Separation of Church and State.” What I’m trying to show is that there was an agreement on the natural rights principles, but at the same time still disagreement about public policy questions about church and state. So the founders are more interesting and more diverse than I think scholars have realized.

Samuel Gregg:

Now, was this something that you came to a conclusion to before and then you wanted to find out if your summation was true or was this something that you came to conclude after reading through some of the texts that are obviously very important for this conversation?

Vincent Phillip Muñoz:

That’s a really good question. I think the light bulb went off when I read a correspondence. I can’t even remember. It was George Washington writing to someone and I just can’t remember whom right now. And he is talking about Patrick Henry’s proposed funding law, a bill for Christian education or education in Virginia. This is right after independence. There’s a debate between Patrick Henry on the one hand and James Madison and Thomas Jefferson on whether religious ministers will be funded in the new state of Virginia.

And George Washington in the letter, again, I just can’t remember, it’s in the book, I just can’t remember to whom it is addressed, says he was originally in support of Patrick Henry’s proposal. So here was George Washington on the one hand, supporting Patrick Henry, a patriot on public funding of religion, and James Madison and Thomas Jefferson on the other side. And I was trying to figure out what all the founders had in common, and they do have something in common. But then it was just obvious, well, they disagreed too. And of course they did. They do have natural rights principles, but what those principles mean in practice, just like we disagree about things, they disagreed about things.

Samuel Gregg:

Well, in light of what you just said, I’d like to quote something that you wrote on page 89 near the beginning of chapter four, which is entitled “The Founder’s Disagreement.” And you write the quote, “While the founders agreed that religious liberty is an inalienable natural right, they began to disagree when they moved beyond the core right to worship according to conscience.” End quote. The natural question to ask I suppose is why did they disagree once they move beyond this essential point?

Vincent Phillip Muñoz:

I don’t know if all listeners that this will resonate with them what I’m about to say, Thomas Aquinas says, “When you move away from the first precepts of the natural law to more secondary considerations, what the natural law dictates becomes a little less clear.” And I think it’s an analogous to that. The founders agreed, what I say is an inalienable right, their language was an unalienable natural right. And they agreed that means the government has no authority to tell you how to pray, prohibit you from praying, tell you where to worship, mandate worship. So there’s a core agreement. But when it comes to questions like funding, can government fund religious schools? The question in Virginia was, can government fund religious ministers? In the argument, Patrick Henry’s argument was because religious ministers provide education for the citizenry, there’s no public schools at the time. So it was about education according to Patrick Henry. When it comes to these secondary questions, there’s just disagreement about what the natural rights principles dictate. Doesn’t mean that there’s a right answer and wrong answer, just you have to wade through their differences and try to figure it out.

Samuel Gregg:

So you mentioned public education on funding for religious education. What are some of the other, let’s call them policy areas that the founders disagreed about once they moved beyond this core agreement about this right to worship according to conscience as you describe it?

Vincent Phillip Muñoz:

Sure. Another example is can you use religious tests for office? We think of this as a core element of the natural right of religious liberty. It’s actually not so core. In the argument for the pro religious tests for office is something like this, and the context here is let me just use Massachusetts, to be a governor in the state of Massachusetts under its first Constitution, you had to be a Protestant. And that was not uncommon. Other states had religious oaths for office that effectively eliminated Catholics or Jews or non-Protestants. It varied state by state. And the argument that the proponents of the religious tests used was, “Look, we need virtuous office. We need men,” it was all men at the time, “We need men of good character.” This is why we have age limitations. You must be 35 for president or 30 for Senate. And that’s an indication.

The age is a substitute for maturity. Well, they said, “Well, we can use religion as a substitute for virtue.” And it’s clearly a legitimate public purpose to have a limitations on office holding that will foster good character. Religion, some founders said, can be used in that way. And that’s how they justified religious limitations on office holding with the idea that religious liberty is a natural right. And they said, “Yeah, you can worship however you want, but we can use religion as a means to further public purposes such as virtue and office holding.” That’s one side. The other side was no religious affiliation should make no part of the government’s considerations, like a colorblind constitution, race should not be part of the government’s considerations. And so civil rights should not be conditioned on religious affiliation. That’s a second area of disagreement.

Samuel Gregg:

So obviously you’re pointing to considerable ambiguity about the public policy implication of the First Amendment, at least based upon reading what different founders said about these things and the way that they disagreed about these things. So if there is this ambiguity, what does this mean for originalist approaches to the First Amendment today? Because if there is this ambiguity then that suggests that in many cases it’s not immediately evident what the original meaning of the establishment clause and the free exercise clause is, at least as it pertains to public policy questions. So what does this mean for the originalist project of Constitutionalist interpretation, at least with regard to the First Amendment?

Vincent Phillip Muñoz:

Okay, let me just preface my answer by saying it takes me about a hundred pages to answer this question in the book. So I’m going to give you the short version. The first thing we should, just because one founder said something doesn’t mean that’s the founding position on church and state. And you see this in jurisprudence, a citation to Jefferson or Madison. And because Madison said this, usually this is misinterpreted, but that’s another problem because Madison said this, then therefore the First Amendment means that. And that’s just a lazy way to do jurisprudence. And look, both sides do this. Conservatives do it. Liberals do it. It’s just irresponsible, to speak candidly. Okay. The other thing it indicates, the founders disagreements, if you are aware of the disagreements when you go back and read the historical record, the historical record starts to make more sense. They disagreed about the proper relationship between church and state.

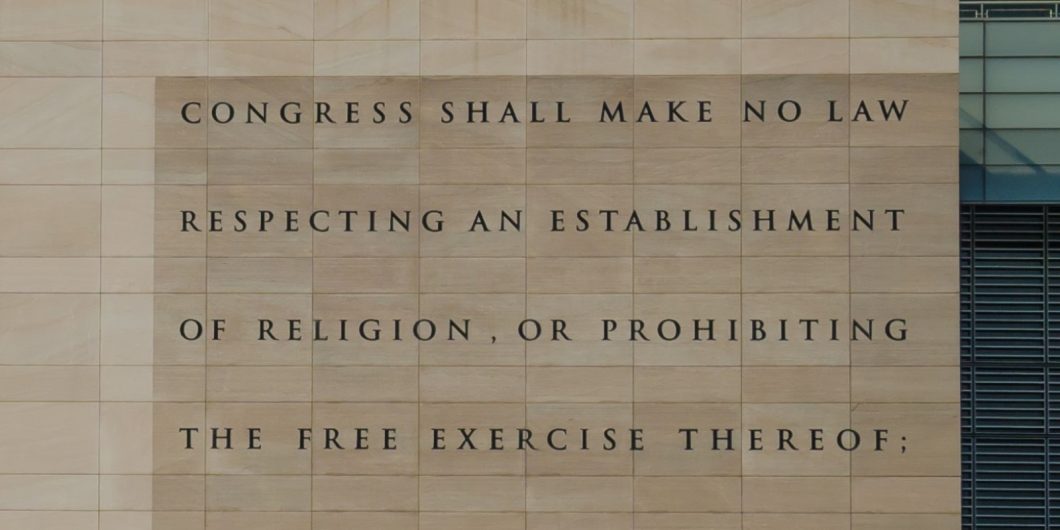

One of the ways we deal with disagreement at the time of the founding, less so now, but at the time of the founding was federalism. So part of my argument was the establishment clause and the odd language, respecting an establishment. Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment. One of the purposes, not the only purpose, but one of the original purposes was to say, “Hey, we disagree about these church-state matters. We will leave them with the states.” And that’s how knowledge of the disagreement starts to shed light on what they were actually doing when they drafted the First Amendment.

Samuel Gregg:

So given that’s the case, what role do you think that the idea of natural rights has in terms of constructing a coherent originalist interpretation of the First Amendment in light of the fact that the founders clearly did disagree about some very important questions regarding religious liberty that are still playing out today? So what does the natural rights approach to this suggest in terms of how one should construct an originalist approach to the First Amendment?

Vincent Phillip Muñoz:

Okay, so let me just start on the level of you’re a good faith legislator trying to understand what your constitutional power is or judge trying to interpret the First Amendment. What would this knowledge of natural rights, how would it help you? Well, first of all, I talked about the establishment clause already, let me talk a bit about the free exercise clause. The First Amendment says, “Congress shall not prohibit the free exercise of religion.” Well, what is the free exercise of religion? It’s not a term of ours. There’s not a clear meaning of the free exercise of religion. So you have to go beyond the text. You can’t just, “Well, the text is obvious.” Text is not obvious at all. Well, how did the founders conceive of the idea of the free exercise of religion? If you go back to what they wrote about religious free exercise, you see they called it an inalienable natural right.

Well, what’s an inalienable natural right? Again, this is a whole chapter in the book. An inalienable natural is a right over which we do not give authority to government. That’s why it’s inalienable. That term is actually very important. It refers to social compact theory. We don’t give a certain degree of authority to the government over our religious exercises according to the founders. I’m going to make a big jump here. The core of that right was the right to worship, the right to worship according to conscience. What that means in practice is government has a jurisdictional limitation. It has no authority to tell you how to worship, to make legislation saying, “You must worship in this way at this time in this church.” So the question was what does the natural rights, or what does the knowledge of the founder’s natural rights philosophy do for constitutional interpretation? It gives us a way to understand the terms they use, the free exercise of religion, how they would’ve conceived those terms.

Samuel Gregg:

So you say it in the book, you say you’re offering a method of interpretation that I quote, “Does not correspond to any existing jurisprudential approach.” So tell us about how your approach differs from the primary ways in which the Supreme Court has approached First Amendment cases and how your approach might yield some different decisions to what we’ve been seeing coming out of the court in say, the past 10 years on these first amendment issues?

Vincent Phillip Muñoz:

Okay, sure. I’m going to group, I hate doing this, but it’s just for convenience, I’m going to do it. There’s I’m going to call it, a liberal approach and a conservative approach. I don’t actually think those terms are really appropriate, but nonetheless, that’s how people think about these things. So the liberal approach says, “Thomas Jefferson erected a wall of separation. That’s the understanding of the establishment clause.” And then they take off running. What does a wall of separation mean? Now they say all of this is originalist because Thomas Jefferson erected the wall of separation and that’s how we get the lemon test, the endorsement test, and other subsequent tests that impose the strict separation of church and state. I don’t think any of this is really originalist. They don’t really understand what Thomas Jefferson said. They take one metaphor, just for the record, Thomas Jefferson had nothing to do with the drafting of the First Amendment.

He advocated a Bill of Rights, but he was in Paris at the time the first Amendment was drafted. He had no direct connection. The wall of separation comes from a letter he wrote in 1802. So to even use Jefferson is a little bit specious. But that’s a different problem. But they take this idea of a wall of separation and run with it. Conservative judges do something a little bit different. They don’t know what the text means either. They recognize the text is ambiguous, so they go to traditional practices.

Did the first Congress allow chaplains? Yes. Well then chaplains must be okay. Did the first Congress support religion? Well, in some ways they did in the federal territories, the northwest ordinance. So I guess that means support of religion is okay. So they look to traditional practices, especially the practices of their early founders. That’s a common way of doing jurisprudence. There’s much to be said for it, but that’s not how the founders talked about religious liberty. It’s not really originalist. When the founders talked about religious liberty, they used natural rights language. So if you really want to follow the founders, now it’s a different question of whether we should, but if you really want to follow the founders, you have to understand how they conceived what they thought religious liberty was.

Samuel Gregg:

So you’re arguing in a sense for a more philosophical approach to this rather than, let’s call it a historical approach to understanding what the original meaning means?

Vincent Phillip Muñoz:

That’s exactly right. I find that compelling because I think it reflects actually the founder’s understanding. You could say there’s an interesting historical question. How do we understand the founders? By what they did or what they said? And that’s a rich historical question. I think we should understand the first amendment by what they said and then the philosophy behind it, not simply by their actions.

Samuel Gregg:

That brings me to the next question I wanted to ask you, very naturally actually. So you make it very clear that the founders by and large understood religious liberty as an inalienable natural right. Now this idea obviously did not just pop out of nowhere. So where did that understanding in your estimation come from? Is this a straight translation from say, Locke’s letter on toleration or is it derived from older natural law sources like Protestant natural law theorists like Hugo Grotius or even medieval natural law thinkers or some combination of these sources? Or was there something distinctly American in the way that the founders talked about religious liberty as an inalienable natural right?

Vincent Phillip Muñoz:

Yeah. Good. That’s a difficult question. Let me tell you what I try to do in the book and then give a fuller answer to your question. What I try to do in the book is just simply present the clear evidence that they talked about religious liberty. This way it’s very easy to show. You just go to the early state constitutions. There was a great period of constitution making between 1776 and 1791 in America, mostly at the state level. Obviously we made the federal constitution as well. In these early state constitutions, there are declarations of rights, and these were not law per se, but they were statements of political principles. And when you go back and read those declarations of rights, what you see is they all say the same thing about religious liberty. It’s a inalienable natural right or it’s a natural right. So that’s the evidence that the founders conceived religious liberty as a natural.

What I then try to do is explain using Isaac Backus, one of the most important Protestant ministers at the time, a Baptist minister, Thomas Jefferson, who’s my representative of secular enlightenment philosophy, John Locke in particular. And then James Madison, who’s interesting—he’s really unique, his natural theology. I try to show how through the traditions of secular philosophy, protestant theology, and natural theology or natural philosophy, how the founders themselves conceived the natural right to religious liberty. I don’t trace the intellectual heritage of that thinking. That’s a different project really beyond my expertise. Certainly you can see elements of Locke in Jefferson’s thought without a doubt. You can see elements of Locke in Madison’s thought. But Locke, as far as I know, never uses the language of inalienability. That’s a maybe uniquely American conception, consistent perhaps with Locke, but different than the language he uses. And then of course there’s a rich Protestant tradition. We tend to oppose in light of philosophy or lacking in philosophy with Protestantism, but the founders didn’t and I tried to show the harmony in their own thinking.

Samuel Gregg:

So is that where you would identify something distinctly American in the way that the founders talked about religious liberty as an inalienable natural right? It’s a combination in a sense of Protestant thinking about this particular question as well as obviously enlightenment ideas about toleration that were becoming much more widespread in, let’s call it the North Atlantic world at this particular point in time?

Vincent Phillip Muñoz:

Yeah, I think that’s right. And if you really push me, though this will make my integralist friends go crazy, I think you can even find at least the preconceptions of a distinction between church and state and the makings of the beginning of an idea of a political right or civil right to religious liberty. And even the thought of Thomas Aquinas, that’s a different podcast. But I think you’re right to see, and what I’m trying to show is there are both theological and philosophical influences that the founders draw upon, but I just try to explain the founders as they presented themselves.

Samuel Gregg:

Well, you won’t be surprised to hear me say that. I think you’re right about Aquinas and I read other scholars who’ve suggested in this regard that you can find a type of argument for religious liberties and natural right in medieval canon lawyers. But as you say, that’s a different discussion for a different podcast. I’d like to move towards the end now, but I’d really like to shift the discussion in a different direction. And it concerns part of your book that at least I found especially interesting, and that’s perhaps because it’s the area that I knew the least about before reading your book. And this concerns something you mentioned before, which is the way that different states and different state constitutions treated religious liberty. In fact, on pages 58 to 59, you list all the different provisions of the different states about religious liberty of and from worship between 1776 and 1786. So this leads me to two questions. First, what influences, if any, did these texts have upon the first amendment? Second, what were the starkest differences between the various state provisions for religious liberty?

Vincent Phillip Muñoz:

Let me start with the second question because that will help me address the first, the starkest differences I think are the state of South Carolina’s 1778 Constitution of South Carolina. And then the Virginia Constitution as drawn out or filled in by Jefferson’s Virginia statute for religious liberty. So the 1778 South Carolina Constitution, it’s the one founding era state that actually established a religion.

Samuel Gregg:

Only one. Because you often hear people talking the states.

Vincent Phillip Muñoz:

Everyone says six or seven states established a religion. They say that because Leonard Levy, famous scholar, not always fully truthful scholar, famous scholar said six or seven states had established religions. The reason Leonard Levy said that is because he said, “If a state funded religion, it had an establishment.” But he was imposing a definition of establishment. He was taking a mid-20th-century jurisprudential category. If you fund religion, you have an establishment and reading it backwards. The founders did not associate, at least not all the founders funding a religion with establishment. And that’s one of the things I try to show. The language on whether you could or could not fund religion was separate from language concerning an establishment. So you have the South Carolina constitution that says, “We have an established religion.” What that meant is certain religions, you had to be Protestant to be incorporated.

The state constitution prescribed articles of faith. It prescribed how ministers were selected. The state had authority to limit how much a church could raise every year. The state delegated taxing power to churches. This is all part of an establishment.

On the other hand, if you go to the 1776 Virginia Declaration of Rights and then the 1786 Virginia statute for religious Liberty, Madison and Jefferson said, “No one’s civil rights should be affected, both positive or negative according to religious affiliation.” That’s the range. That was your first question.

How does this all impact our understanding of the First Amendment? Well, as I alluded to before, because there are real differences, there was a real motivation to keep these questions at the state level and you see that in the respecting an establishment. If we said, “Federal government should make no law respecting abortion.” We would immediately understand it. Oh, because that’s a state question. I don’t want to repeat what I said before. At the same time, the natural rights philosophy gives us an indication of the substance of the free exercise class.

Samuel Gregg:

So here’s my last question and it’s very much directed to contemporary circumstances. What does your message about religious liberty and the way that the founders understood it, what do you think the most important message is on the one hand for those who take a, let’s call it liberal approach to questions of the First Amendment? And what does your approach say to those who take, let’s call it a conservative approach to the First Amendment?

Vincent Phillip Muñoz:

Yeah. Well, I should say, I’m not trying to advocate my approach, I’m just trying to set forth the founders’ understanding as best I understand it and as clearly as I can express it. So if you don’t like the argument of the book, blame the founders, don’t blame me. I’m pretty candid in the conclusion. I try to assess it. My voice comes out in the conclusion. I say, “This is what I see as the strengths of the approach. This is the weakness of the approach.” So I’m just trying to operate as a scholar here. If there’s one thing I’m trying to show, it’s that judges have abused the founders and misused them. They’re really rewriting the First Amendment.

Samuel Gregg:

And you mean judges who would self-describe themselves or be described as liberal and conservative on these issues?

Vincent Phillip Muñoz:

Yeah, more so the liberals, but also the conservatives to be honest. Now whether this is malicious or accidental, I think it’s pretty obvious when it’s malicious. It’s maybe less obvious if it’s accidental. But either way, they’re rewriting the First Amendment and that’s one of the things I’m trying to show. Now we might like that rewriting or we might not, but let’s have an argument about it. To have an argument about it, you first have to see what’s been done.

Samuel Gregg:

And that seems like a good point to end our discussion. Professor Phillip Muñoz, thank you very much.

Vincent Phillip Muñoz:

It’s a pleasure. Thank you.

Samuel Gregg:

You’ve been listening to Liberty Law Talk in which we’ve been discussing Professor Phillip Muñoz’s, new book, Religious Liberty and the American Founding: Natural Rights and the Original Meanings of the First Amendment Religious Clauses, published by the University of Chicago Press and available at Amazon, as well as all good bookstores. This podcast is available here at the Law & Liberty website and all good podcast sites like Apple Podcast, Spotify, and Pod Chaser. If you like what you hear, please give us a five star rating to encourage more people to join us every month. I’m Sam Greg for Liberty Law Talk. See you next time.

Brian A. Smith

Thank you for listening to another episode of Liberty Law Talk. Be sure to follow us on Spotify, Apple, or wherever you get your podcasts. And please visit our journal at lawliberty.org.